CAA News Today

International Review: Gordon Walters: New Vision by Leonard Bell

posted by CAA — Dec 06, 2018

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Leonard Bell, professor of art history, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Exhibition and catalogue review: Gordon Walters: New Vision, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 11 November 2017- 8 April 2018, and Auckland Art Gallery, 7 July – 4 November 2018.

Marti Friedlander, Portrait of Gordon Walters in His Studio, 1978, Marti Friedlander Archive, EH McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Courtesy Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust.

The much-lauded work of Gordon Walters (1919-1995), one of New Zealand’s first geometric abstract painters, has also generated controversy. A retrospective show traveled the country in 1983, but the present exhibition is the first comprehensive survey of Walters’s complete oeuvre from the late 1930s until his last painting in 1995. A wonderful show, curated by Lucy Hammonds, Laurence Simmons, and Julia Waite, it clearly establishes Walters’s greatness as a painter. Walters’s art was informed and sustained by an extensive knowledge and sophisticated understanding of Euro-American—Piet Mondrian (principally), Sophie Tauber-Arp, Joseph Albers, Auguste Herbin and John McLaughlin, for instance—and Oceanic art, in particular the koru motif of Maori kowhaiwhai (painting, on rafters and paddles, for example) and moko (tattoo). Add to those his early, unusual-in-New Zealand interest in Surrealism and the idiosyncratic sketches of a mentally ill man, Rolf Hattaway. Walters learned about these from a close friend, émigré Dutch artist Theo Schoon, an ardent advocate of Bauhaus practices and Maori visual arts, especially “primitive” rock art.

The resultant body of work constitutes an imaginative and distinctive interweaving of elements from diverse societies and cultures. Formally and technically rigorous, visually refined, conceptually deep, Walters’s paintings are both still and tense. While pulling in different directions, his best known work, the so-called koru paintings, somehow betoken their place, a cluster of islands in the southwest Pacific. Their imprint extends far beyond the art world, to the New Zealand Film Commission’s logo, for instance. Yet, to present Walters’s art only in terms of these koru paintings would skew the overall picture and leave it incomplete. The exhibition rightly gives as much attention to his many other different paintings.

Sydney Parkinson, painted Maori paddle, 1769, Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Cambridge, UK.

Since Walters’s breakthrough shows at Auckland’s New Vision Gallery in 1966 and 1968 (his first since an early exhibition in 1949), writings about his art have proliferated. His abstractions attracted the keen attention not only of New Zealand art historians, critics, and philosophers, but also the eminent British critic Robert Melville (Architectural Review, 1968), who regarded Walters’s paintings as the best he encountered in New Zealand, polymathic Ernst Gombrich (The Sense of Order, 1979), as well as Australian art historians Rex Butler and A. D. S. Donaldson, and American Thomas Crow (in the present catalogue). The handsome publication reproduces a rich feast of Walters’s works. Nine writers produced eight essays exploring various aspects of Walters’s art and career. Several essays (notably by Peter Brunt and the Australians) offer new details and connections between Walters and other artists.

The trajectory of his career, his primary inspirational sources, his paintings’s formal qualities and conceptual substance, though, have already been intensively excavated, especially by Michael Dunn in the 1970s and 1980s, and Francis Pound from the mid-1980s until his death in 2017.

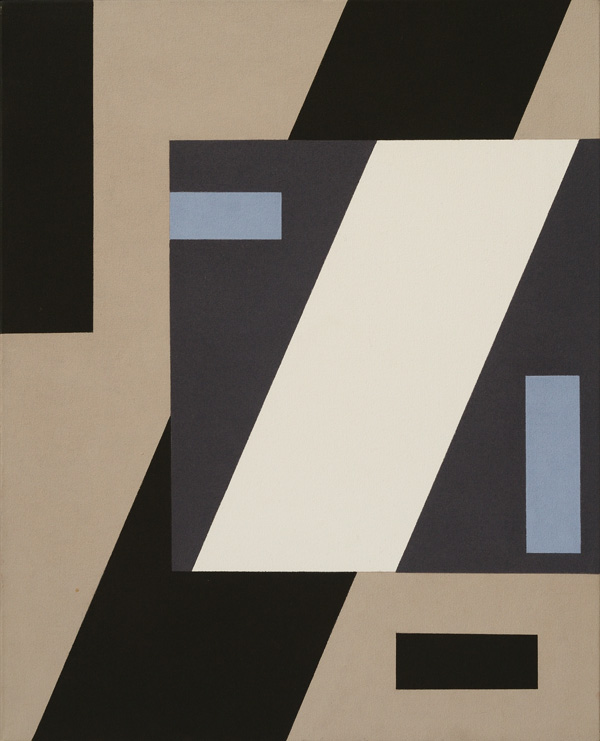

Gordon Walters, Untitled, 1989, Collection James Wallace Arts Trust, gift of the Rutherford Trust.

In an exhibition review in Art News New Zealand (Summer, 2017), David Eggleton observed, “Curiously, Pound is an absent if also an insistent presence in the catalogue of the show. Although not included as a contributor, many of the ideas and notions first proposed by him appear in the text, subsumed into the writings of others.” And a festschrift in 1989 to mark his 70th birthday, Gordon Walters: Order and Intuition, edited by James Ross and Laurence Simmons, had ten scholarly essays, including (disclosure) my “Walters and Maori Art: the nature of the relationship?”

Transformation of his inspirational sources characterizes Walters’s art. His first investigations of the Maori koru motif, small studies in ink and gouache, appeared in the mid-1950s. They were close to the source; the motif’s organic quality was semi-retained.

In the mid-1960s Walters geometricized the form. Except for circular shapes terminating the crisply delineated bars, curves were straightened out. The reshaped element provided a means, in league with Mondrian et al, for studies in formal relationships using a “deliberately limited range of forms” (Walters, 1966).

These were not intended to draw on the Maori motif’s symbolic values, though Walters’s use of Maori terms for many titles was an acknowledgement of the inspirational importance of Maori art as he had experienced it.

From the mid-1980s, most forcefully in the 1990s, possibly triggered by critiques leveled at the Museum of Modern Art’s 1984-1985 exhibition, Primitivism: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, Walters was accused of exploitative appropriation of Maori art by several critics, both Maori and Pakeha (European New Zealander).

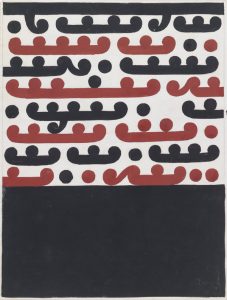

Gordon Walters, Gouache, 1957-8, Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena.

Others, including Maori and Pakeha artists, also defended Walters. The catalogue touches on this sometimes acrimonious argument, though the exhibition’s wall texts and captions bypass it. Deidre Brown’s catalogue essay, “Pitau, Primitivism and Provocation: Gordon Walters’ Appropriation of Maori Iconography,” steers a near-neutral path between the antagonists, culminating with the claim that they moved onto other concerns: “the appropriation debate faded away from academic art history.” Several reviewers, though, questioned whether the contentious issue was satisfactorily addressed by the show.

Most of Walters’s detractors and advocates assumed a straightforward relationship between his work and Maori art: cause = koru motif and effect = the forms in Walters’s koru paintings. The detractors appeared to subscribe to a Manichean structure of polarities in which modernist borrowings are, ipso facto, “bad.” In this system a single component in the works becomes the only or dominant one. If the same paintings are seen within wider cultural and historical contexts, though, an interplay of multiple elements and global connections, in which no single one is dominant, becomes manifest. A complex of factors also mediates how Walters’s koru paintings have functioned. Depending on the kinds of knowledge and cultural baggage individual viewers bring to the encounter, they are clearly perceived very differently. Indeed, one could well wonder whether viewers with opposing perspectives are talking about the same pictures. The diverse opinions resist resolution; the conflicting perspectives are incommensurable. Just as creationists are unlikely to accept a logical refutation of the existence of “God,” so Walters’s critics are not likely to see his art in any other way than their own.

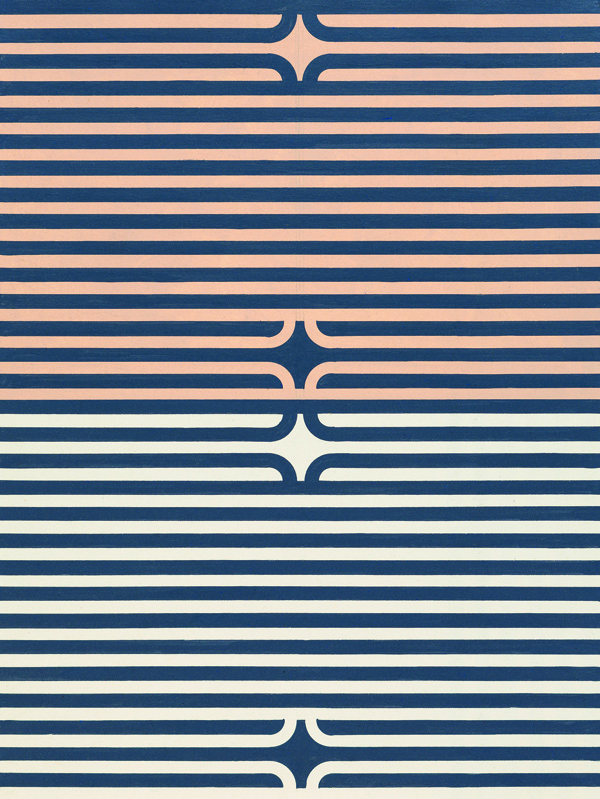

Gordon Walters, Painting No. 1, 1965, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Purchase 1965.

Take another slant. In 1910 the New Zealand Herald reported a “curious discovery” by Mme Boeufvre, wife of New Zealand’s French consul. Seeing the Book of Kells (c. 800 CE) in Dublin, she “was much struck by the similarity of Celtic ornaments to Maori conventional designs…how very closely the Maori patterns resembled those of the ancient artists of Ireland.” Since the nineteenth century parallels were frequently drawn between curvilinearities in Maori artifacts and those in the art and ornament of other societies, including such varied cultures and aesthetics as Egyptian, Greek, South East Asian, Victorian, and Art Nouveau, in addition to Celtic. For instance, renowned Austrian art historian Alois Riegl (‘Neuseelandische Ornamentik’, 1891, and Stilfragen, 1896) matched Maori and Egyptian spiraling forms. He noted that they could not possibly have had the same origin. Like many other forms, that of the swastika, for example, the form of the Maori koru motif is found all over the world. There is no singular point of invention.

Universal and local collide in Walters’s painting. Was Walters indigenizing the modern or modernizing the indigenous—or both, or neither? Can we look through several lenses simultaneously? Compelling art certainly can emerge from socio-cultural dissonance—Walters’s paintings continue to energize the spaces they inhabit. They have a contemporary urgency, informing the work of contemporary artists of both Pakeha and Maori descent, such as Darren George and Chris Heaphy. (The latter worked with Walters in his last years.) For others tension between Maori and Euro-American aesthetics and practices remains. Walters’s painterly synthesis of Maori, Oceanic, European, and American elements and ideas was virtually unique among Pakeha artists in his time. He trod a solitary path. In retrospect, though, his oeuvre constitutes a crucial watershed, in which the possibilities of bicultural coexistence of things Maori and Pakeha were explored, celebrated and contested.

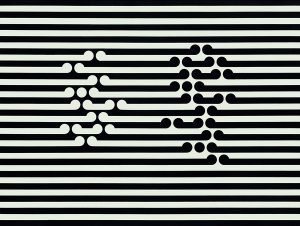

Gordon Walters, Untitled, 1972, Dunedin Public Art Gallery Loan Collection, Courtesy of the Gordon Walters Estate.