A Global Vision: The CAA-Getty International Program

Peripheries of the World, Unite!

—Piotr Piotrowski

With this title, the influential Polish scholar Piotr Piotrowski spoke in 2013 at the annual Congress of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) in Košice, Slovakia, calling for a nonhierarchical, art historical analysis on a global scale, what he termed “horizontal” art history. The conference was co-organized by Richard Gregor, an alumnus of the CAA-Getty International Program, which had begun two years earlier with a similar, if less overtly political, goal. Piotrowski’s call to action, however, evokes the personal commitment, enthusiasm, and camaraderie that characterize the ten-year-old community of CAA-Getty scholars.

Fig. 1. Richard Gregor presenting a paper as part of a 2017 CAA-Getty International Program reunion session, held at the CAA Annual Conference (photograph by Ben Fractenberg, © CAA)

The CAA-Getty International Program grew out of a precursor program run by the National Committee for the History of Art (NCHA) between 2009 and 2011, during years that Frederick M. (Rick) Asher was its president. The goal of that program was to gain an understanding of the diverse practices of art history by bringing international scholars to the annual conferences of CAA (College Art Association). CAA picked up where NCHA left off, receiving its first grant from the Getty Foundation in 2011, in time to bring international colleagues to the 2012 conference. It has been my pleasure and privilege to direct the program ever since, working with NCHA, especially Rick, and CAA’s International Committee, especially its chairs, to bring it to life.

From this vantage point, I have been able to observe over time the coming together of scholars from disparate countries and backgrounds. Each year, when fifteen to twenty participants arrive at the Annual Conference, they bring with them an equal number of interests, points of view, and experiences. It is their contributions, many of them ephemeral, that have created the ongoing global conversations. Comprising preconference papers and discussion sessions, informal conversations over coffee or dinner, and shared outings to museums and galleries, their activities are the building blocks that have accrued to become greater than the sum of their parts: they have created a replicable model for international scholarship that makes a substantial contribution to the field. My purpose in writing this essay is to document and share some of these conversations, to glean from them key themes and questions, and to preserve the first ten years of the program as a significant chapter in the history of global art history.

Fig. 2. Deborah Marrow, Eddie Butindo-Mbaalya, Cezar Bartholomeu, Hugues Heuman Tchana, Freeborn Odiboh, and Eric Appau Asante, 2014 (photograph by Bradley Marks, © CAA)

It is just as well that CAA began its program without Piotrowski’s more specific political aim. As stated in the original 2011 grant application to the Getty Foundation, the goal was “to support travel and accommodation expenses for twenty international art historians (including artists who teach art history and art historians who are museum curators) from countries not well represented in CAA membership. . . . We want participation to grow in order to bring a more diverse perspective to the discipline and connect art histories from around the world.” Starting with a general belief that adding diversity to the conversations would mutually benefit American and international scholars, our approach was straightforward and open-ended. Via an application process, we selected scholars from underrepresented countries who had not attended CAA conferences previously. Based on their interests, we introduced them to scholars from the United States and Canada who were attending the conference and provided opportunities to meet in small groups. Since that first conference in 2012, the program has grown organically, adding preconference events, conference sessions, and online discussions—the thematic topics determined as much as possible by the international participants—to culminate, ten years later, in a vital global community now comprising 135 alumni from fifty countries.

From the beginning, an interest in international topics and issues and, for most, a PhD in art history or a related field (such as visual culture, aesthetics, postcolonial studies, gender studies, and cultural heritage research) have remained the two constants in an otherwise heterogeneous group of people. Coming from diverse countries on six continents, participants have ranged in age from their mid-twenties to mid-sixties; from scholars educated in their own countries to those educated in Europe, the United Kingdom, or the United States; from specialists in ancient art to those studying contemporary works; and from those who teach at universities or work at research institutes to those who work as curators in art museums.

Had we consciously set out to fulfill Piotrowski’s call, we might have felt obliged to follow his recommended methodology, with the goal, as he put it, “to subvert or invert mainstream art history.” He suggested using deconstructive and constructive methods to clarify that the West is only one of many provinces for art and scholarship and, equally important, to build new, interrelated, histories through a horizontal study of the topic. I would say the CAA-Getty program, with less intentionality, has intuitively enacted his call, evolving iteratively from year to year to explore effective means of creating inclusive discussions. Through dozens of papers presented at the program’s preconference colloquiums and, since 2017, at its Global Conversations conference sessions, participants have explored topics such as artistic migrations, colonial legacies, challenges of language, translation, and terminology, social and political inequalities, museum issues and responsibilities, and disruptive pedagogies. What I hope to capture here are the remarkable conversations that ensued among the program’s participants—both the international scholars and their US-based hosts—about the nature of art and especially its study, historically and in the present day.

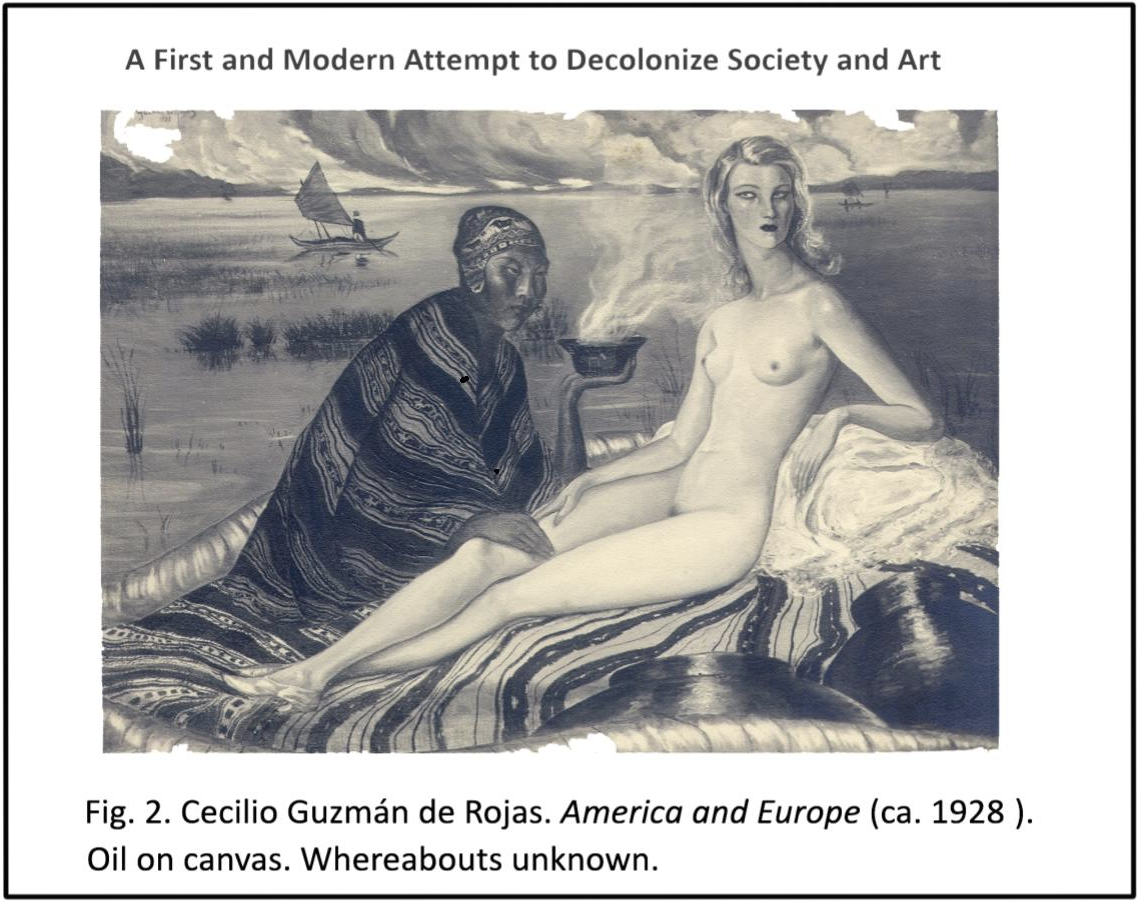

Fig. 3. Slide from “Neither One nor the Other: Thinking Art beyond the Colonial Bind,” a paper presented by Valeria Paz Moscoso at the 2020 preconference colloquium, with painting by Cecilio Guzmán Rojas (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by Valeria Paz Moscoso)

As early as the first meeting of the CAA-Getty International Program in February 2012 (then called the CAA International Travel Grant), two participants contributed comments related to Piotrowski’s theme. Federico Freschi, then in South Africa and now in New Zealand, noted the importance of bringing together scholars from around the world; but, he asked presciently, “Are we forming new kinds of paradigms, ways of thinking?” And Cristian Nae, from Romania, characterized this new dialogue among participants as “connecting peripheries.” The two went on to consider “a new north-south axis” extending from Eastern Europe to South Africa, an area they observed was markedly lacking in cross-cultural study or exchange. A year later, Judy Peter, another inaugural year participant from South Africa, joined forces with Nae and two 2013 participants, the above-mentioned Richard Gregor, from Slovakia, and Karen von Veh, from South Africa, to form a spin-off research project, EESA (Eastern and Central Europe and Southern Africa: Between Democracies: Remembering, Narrating and Re-Imagining the Past in Eastern Europe and South Africa), which organized exhibitions, publications, and international exchanges from 2014 to 2020. (The collaboration was expanded by Nae in 2021 to include two additional alumni, Giuliana Vidarte, from Peru, and Màrton Orosz, from Hungary, in a new project: Environmental Utopias: Artistic Responses for a Planetary Future, which was based on a Global Conversations session at the 2021 CAA Annual Conference.)

From its inception, geographical perspective, national identity, and transnational study have been frequent topics of discussion in the CAA-Getty program. A review of the topics of papers presented at the preconference colloquiums and conference sessions (see Appendix B) reveals the evergreen themes of decolonization and postcolonial legacies, global versus local, cultural identity, and the migration of art and ideas. Beginning in 2016, as part of the planning process for the program’s fifth anniversary events, to take place at the 2017 CAA Annual Conference, we introduced online discussions during the spring and summer to further explore conference themes and to determine topics for the following year’s sessions. These discussions, conducted on software platforms such as Humanities Commons, were not intended for publication (throughout this essay, I quote from them with permission), but I think the fact that they were written to field ideas and draw on fresh perspectives, away from concerns about public assessment, contributes to their personal, thought-provoking, and compelling nature.

Fig. 4. Nomusa Makhubu introduces 2018 Global Conversations session “Border Crossings: The Migration of Art, People, and Ideas” (photograph by Ben Fractenberg, © CAA)

In one online discussion—characteristically free-flowing and wide-ranging—a group of alumni explored the subject of migration, taking as a starting point a Global Conversations session in 2018 titled “Border Crossings: The Migration of Art, People, and Ideas” (see 2018 Global Conversations session in Appendix B). Nomusa Makhubu, an alumna from South Africa and then a member of CAA’s International Committee, who had served as moderator of the “Border Crossings” session, led a portion of the online discussion. She began by commenting on recent posts discussing types of migration. “One wonders if our challenge as art historians is about how we use the ‘national’ as a way of classifying or as an analytical tool or whether our (global) practice is actually signaling the porosity of those borders.” She then posed a question: “In your work, how does the sense of place influence your research (in various creative practices); i.e., do you see the ‘national’ as something useful (providing contextual focus), or is it something limiting (obscuring supra-national socio-cultural intricacies)? How do you navigate the ‘national’ and the ‘global’ (or glocal), not only in terms of physical resources but also in terms of the methodological and theoretical approaches to your work?”

Sarena Abdullah, from Malaysia, contributed, “In my own work (because I have been working across various periods, both before and after Malaysian Independence), ‘national’ and ‘nationalism’ are convenient concepts to define what is the mainstream narrative of Malaysian art and what is not. . . . Taking up a new concept of examination, e.g., global art history, migration, or international circulation, does not mean that the idea of ‘nation’ or ‘national’ in art history is passé or obsolete or of no value. . . . Although I mostly work within the construct of national art history, my examination of visual culture in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Malaya requires me to use a different framework—hence, cosmopolitanism (in my opinion, the concept allows us to be citizens of the world)—which allows me to study works of art also as a translation of ideas, the adoption and adaptation of styles, and the eclectic selection of various formal elements.”

Most respondents rejected the word “national,” even as they acknowledged the importance of a sense of place. Katarzyna Cytlak, a Polish scholar then living and working in Argentina, wrote about hybrid nationalities, about the formation of identities that cross cultures, and cultures that combine more than one identity. Simon Soon, from Malaysia, contributed the term “migrant cosmologies,” which he uses to describe the impact of a Javanese house temple within a Chinese village in Malaysia. He described a “transhistorical allegiance” emerging from the diverse architectural details of the temple that created a cultural bond between two working-class migrant communities (Chinese and Javanese) across the twentieth century.

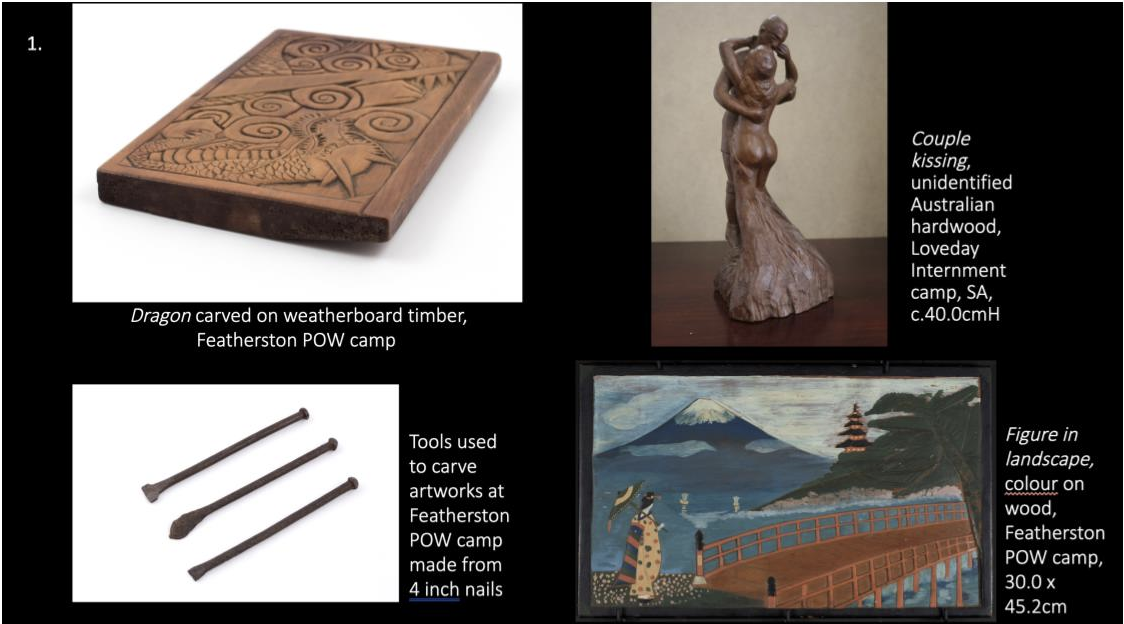

Observing the centrality of migration in their research, several participants elaborated on its attributes. Fernando Luis Martínez Nespral, from Argentina, wrote about migration as displacement. He quoted an observation attributed to the American novelist John Gardner: “There are only two kinds of stories: A person goes on a journey, or a stranger comes to town.” He went on to say, “I always remember this idea of Gardner’s because I believe that some kind of displacement (of people or ideas) is indispensable for any creative process. This displacement can be forced (exiles), voluntary (migrations), temporary (travels) or even mental (through readings for example).”

Fig. 5. Artworks exemplifying forced displacement/exile. Slide from “Art by Japanese Prisoners in New Zealand during WWII,” a presentation by Richard Bullen at the 2019 preconference colloquium (photograph provided by Richard Bullen)

Georgina G. Gluzman, also from Argentina, pointed out the gender bias in migration studies: “The area of Latin American studies has always dealt with the processes of migration . . . however, in my case, the topic of moving around intersects with gender, as I work on the lives and careers of women artists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. In Argentina the history of modern art has been written as a masculinist tale of mastery and discovery. These two key concepts intertwine with the concept of mobility and migration. . . . To sum up, I believe that any focus on migrant artists needs to be intertwined with the specific positions the individuals had in the society, particularly with gender.”

Alison Kearney, from South Africa, expressed a preference for the term “border crossing” to “migration”: “For example, I use the term ‘border crossing’ to describe the movement of beadwork from what was (wrongly) considered to be a ‘traditional craft,’ and therefore static art making practice, into contemporary ‘high art’ and haute couture. In the discussion I critique the binaries that are part of established discourses and show that beadwork has always been in flux, dialogic, and part of the contemporary. . . . I am particularly interested in how the same objects acquire new sets of meanings when they are part of art, since we look at them in particular ways linked to the operation of the fields of art, and the structures like art history and the gallery, museums and curricula.”

Fig. 6. Nazar Kozak in the Rothko galleries at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, 2016 (photograph © Márton Orosz)

By the time of the 2019 online discussion, the topic had shifted and expanded to consider geographical perspective as one among many subjective aspects of art historical study, including questions of positionality, the “power struggle of interpretations,” and divergent viewpoints over time. Nazar Kozak, from Ukraine, began the discussion by asserting the value of revisiting works of art. He used the expression “objects déjà vu”: “To make progress our knowledge system has to be constantly reinvented: we need new approaches to familiar stuff; we need that déjà vu effect—an unexpected look on what we thought we knew very well.”

Stephen Fọlárànmí, from Nigeria, who had already demonstrated a vast knowledge of Yoruba proverbs during the previous Annual Conference, contributed two sayings about relative perspective: “‘What faces an individual, backs another.’ In other words, we sometimes or in many instances view issues from different perspectives. The other proverb simply says, ‘You assume that your father’s farm is the biggest because you haven’t visited another farm,’” pointing to the limits of experience in shaping one’s perspective and understanding.

Chen Liu, a Chinese scholar of the Italian Renaissance and its reception in China, contributed a poem by the eleventh-century poet, painter, and writer Su Dongpo:

From the side, a whole range; from the end, a single peak;

Far, near, high, low, no two parts alike.

Why can’t I tell the true shape of Mount Lu-shan?

Because I myself am in the mountain.

Chen wrote, “The poem was written almost a millennium ago but has since made a legend of itself as a timeless metaphor of the ever-shifting perceptions of human beings, a literary ‘theory of relativity’ with a philosophical dimension. Being an artist himself—he excelled in both painting and calligraphy—Su Dongpo knew all too well the infinite and indefinite appeal of the object, which in the poem’s case is represented by a mountain (Mount Lu-shan), both real and metaphorical. For him, this mountain would be not only an example of ‘déjà vu,’ but also ‘pas encore vu’ (not yet seen), and the second couplet of the poem poses a sharp question to art historians: if we liken objects, artworks, and art historical approaches to a mountain, we can never get a full image or tell the true shape of it; why? Because we ourselves are in the mountain! . . . I think the metaphor of the poem points to a critical situation that all of us art historians are obliged to confront: how far can we go along the path of ‘objectivity,’ at what point should we pause and ponder our relationships with this daunting mountain, would it be possible ever to get a thorough view of the mountain even if we put together everyone, every culture, every period’s perception of it, and, if not, how are we going to move forward?”

Fig. 7. Slides from “A Chinese Perspective on Cross-Cultural Transmissions of Art History,” a paper by Chen Liu presented at the 2018 preconference colloquium

[Fig. 7A]

above: Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, ca. 1492–98, tempera on gesso, 15 ft. 1 in. x 28 ft. 10-1/2 in., irreg. (460 x 880 cm). Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. (artwork and photograph in the public domain; photograph provided by Wikimedia Commons)

[Fig. 7B]

below: Chen Liu (seated in center) and students enact the composition of Leonardo’s fresco, inspired by the ancient Greek practice of ekphrasis (photograph provided by Chen Liu)

These are only some of the sixty posts in this online discussion, which went on to explore other interpretive hazards for art historians. AKM Khademul Haque, from Bangladesh, quoted Rabindranath Tagore on the difference between fact and interpretation: “The truth is what you write, those that happened are not always true.” Pedith Chan, from Hong Kong, posted, “If we look at the familiar with different perspectives we would discover that what we knew was in fact ‘newly invented’ and [citing L. P. Hartley] ‘the past is a foreign country.’” Nomusa Makhubu, the moderator during the second week, moved the discussion to a broader consideration of the tension between distance and proximity, both spatial and temporal. This prompted Parul Dave Mukherji, from India, to observe: “I like the way in our attempt to reimagine our practice, we tend to envisage a topography of a landscape, terrain, mountain and so on. This is very picturesque, but I wonder if this very topography can be reimagined as a desert, dotted with quicksand. How do we radically imagine new tools and new narratives?” Iro Katsaridou, a museum curator from Greece, raised the question of multiple lifespans of works of art—a frequent occurrence in art museums, as objects are reconsidered in changing historical and cultural contexts. Ana Mannarino, from Brazil, added, “The object of art may be the same, but the history of it is always changing.”

The third week of this online discussion was moderated by Pearlie Rose Baluyut, then chair of CAA’s International Committee, who stitched together the many threads of the previous comments with a question about the “fictions of factual representation,” citing Hayden White. She suggested, “It might be helpful for us to build on the fascinating themes that already emerged here and think of our positionality, complicity, and potential through the work that we actually do. Instead of directing our gaze merely to the objects and institutions, could we examine how our experience through these objects and institutions affects the way we think and do art history?”

Many comments followed, including two particularly evocative posts that addressed the subjective and fluid nature of art historical study. Stephen Fọlárànmí contributed another Yoruba proverb: “That pair of shoes on the refuse dump was once worn to a wedding.” And Swati Chemburkar, from India, quoted T. S. Eliot, from the Four Quartets:

. . . And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

I can only say, there we have been: but I cannot say where.

And I cannot say, how long, for that is to place it in time.

Fig. 8. Chen Liu, Nazar Kozak, Katarzyna Cytlak, Nadhra Shahbaz Khan, and Sarena Abdullah presenting the 2019 alumni Global Conversations session “Mapping the In Between across Cultures” (photograph by Ben Fractenberg, © CAA)

The subjective realm, with its indistinct boundaries, changing meanings, and shifting perspectives, is where these international scholars naturally converge. The subsequent conference sessions that arose from these online discussions reflect this character: the 2018 Global Conversations was called “Border Crossings,” the 2019 session was subtitled “Mapping the In Between across Cultures,” and the 2020 session was titled “Things Aren’t Always as They Seem: Art History and the Politics of Vision.”

I quote at length from these online posts to provide a picture of the rich exchanges among CAA-Getty participants that have characterized the program, especially since the fifth anniversary, when alumni began participating in annual conferences as advisor/moderators at the preconference colloquiums and speakers in the (newly created) Global Conversations sessions. These extended explorations were possible both because of new online technologies and because increasing numbers of alumni knew each other personally, forming a close-knit community based on friendship as well as scholarship. The camaraderie that has developed is reminiscent of the close bonds we feel with people who attended the same schools we did.

Nazar Kozak spoke about this when he introduced the preconference colloquium in New York in 2019. “Connections are important because they produce a network, a global network of art historians. This network is informal, ephemeral, unstable, and fragile. The ties that emerge within it are of a different kind than are formed in official institutions like university departments. . . . Contrary to this, the global network of art historians thrives on ‘weak’ ties, which are horizontal rather than hierarchical, situational rather than permanent. They emerge between scholars separated by long distances, acting in divergent education systems, and in different cultures. . . . We need ties of both kinds, and therefore the global network of art historians I have just described is crucial for the professional development of each scholar and the discipline in general.”

Fig. 9. Priya Maholay-Jaradi and Abiodun Akande at the 2020 CAA Annual Conference (photograph © Stephen Fọlárànmí)

Other CAA-Getty alumni have used more personal terms. Abiodun Akande, from Nigeria, wrote: “One thing organizers might not notice is the fact that the CAA-Getty group comes together at the conferences as a family; this is the major difference between our participants and other individual attendees at the conference. . . . The CAA-Getty effort not only benefits individual scholars but continues to bring to the fore the histories of hitherto ‘voiceless’ cultures of the geographic peripheries of the world.”

Geographic location, for all the reasons explored above, is important for yet another reason. It underscores a striking difference between the CAA-Getty participants and the US-based scholars who have served as hosts in the program. With few exceptions most of the international scholars study the art of their own country or region, while in North America, as well as Western Europe, the discipline of art history encompasses the globe. There are many reasons for this distinction, starting with the Eurocentric history of the field, and including vast differences in resources, scale, postcolonial legacies, and language barriers—all issues extensively explored in James Elkins’s indispensable book, Is Art History Global? The distinction here is often subtle because many program participants, as suggested in the above discussions, have ambivalent feelings about the notion of national identity, considering it both defining and limiting. However, they frequently start with their own cultures when exploring cross-cultural or transnational topics. Additionally, many CAA-Getty international scholars are charting new territories within their regions, studying art and elements of visual culture created by women, people of color, Indigenous groups, migrants, and otherwise undervalued or unexplored subjects. Others research theoretical, aesthetic, political, or pedagogical issues. In these various ways, their work transcends geography, since these subjects raise questions that are universal.

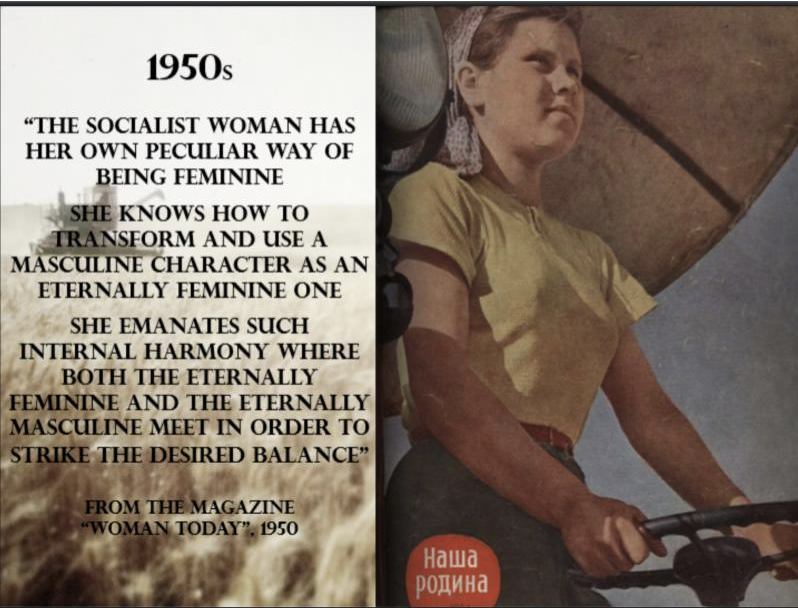

Fig. 10. Slide from “Between Femininity and Feminism: Women (Photographers) after Socialism,” paper by Katerina Gadjeva presented at the 2014 preconference colloquium (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by Katerina Gadjeva)

Let us return for a moment to the spin-off group of participants from Eastern Europe and South Africa mentioned above. Note that these scholars did not recruit US-based scholars to join their work; their planes weren’t stopping in the States. Piotrowski, too, did not invite members of the Western hegemony to join his Peripheries International, though he called on Western scholars to pay attention to their location (i.e., the center ≠ international) and to revise (deconstruct) their scholarship to accommodate multiple perspectives. In fact, the connections formed directly among the CAA-Getty scholars, unmediated by North American scholars, are among the great accomplishments of the program. What, then, is the role for US-based art historians in a gathering of scholars from so-called peripheral countries?

The CAA-Getty International Program takes place, of course, at the largest annual conference of art historians in the United States (and the world), so an introduction to this country’s scholarship—its subjects, issues, methodologies, publications, and priorities—is the first role for US-based scholars welcoming international colleagues. On a practical level, however, attending such a large conference for the first time is a daunting experience; meeting and talking with conference participants is far from guaranteed. Therefore, from its inception, a distinctive feature of the CAA-Getty International Program has been the inclusion of US-based CAA members to serve as hosts, a term chosen to convey a nonhierarchical, personal, and welcoming relationship. The host’s role is to greet the international scholars and optimize their conference experience by recommending sessions and special events of interest, introducing them to colleagues, and frequently taking them to visit local museums. Their participation includes informal conversations at the welcome dinner and scholarly exchanges during the program’s preconference colloquium.

Members of NCHA and CAA’s International Committee have served as hosts since the program began, ensuring a high level of expertise and experience. Significantly, since 2013 NCHA has contributed funds to CAA to provide honoraria to the hosts. Beginning in 2015, scholars active in area-study CAA Affiliated Societies, such as the Association for Latin American Art (ALAA), the African Council of Art Studies Association (ACASA), the American Council for Southern Asian Art (ACSAA), and others, have joined the program in this capacity. These relationships have often extended well beyond the conference program to include joint research projects, guest lectures, and publications. A highlight example is a 2020 book, Art History in a Global Context: Methods, Themes, and Approaches, edited by Ann Albritton and Gwen Farrelly (former chair and member, respectively, of CAA’s International Committee), published by Wiley Blackwell, and featuring chapters by four CAA-Getty alumni—Sarena Abdullah, Parul Dave Mukherji, Cristian Nae, and Judy Peter—and another former International Committee chair, Pearlie Rose Baluyut. By providing personal connections for visiting scholars, the CAA-Getty program successfully combines the valuable resources of a large conference with the personal attention only possible in a small program.

Fig. 11. Georgina G. Gluzman (left) and María Isabel (Marisa) Baldasarre (right), 2016 CAA-Getty participants from Argentina, meet one of their heroes, the art historian Linda Nochlin, at a 2016 conference session titled “Linda Nochlin: Passionate Scholar.” (photograph © María Isabel (Marisa) Baldasarre. See Baldasarre’s article about the meeting in CAA News

Serving as a host is one important role of US-based scholars in the CAA-Getty program. They open the doors to the CAA community and facilitate access to its vast wealth of scholarship and publications. At the same time, American academics represent the “center” in the center-periphery model of the field. Thus, the US-based scholars participating in the program serve another crucial role: to break down the barriers implied by this dichotomy—to open the doors and then work to remove the walls. The aspirational goal of the international project is, ultimately, to erase the duality of the center-periphery relationship, to look instead at interconnections and shared interests.

What has been the impact of the program on the US-based scholars serving as hosts? We know from formal and informal feedback that most hosts found the experience well worth the effort, informative, and mutually beneficial. As mentioned above, several hosts have gone on to coauthor books, exchange visits, and collaborate on research. Ann Albritton, then chair of CAA’s International Committee, wrote in 2013, “The hosts, in particular, benefited both from learning about the recipients’ research in art history and the opportunity to share mutual interests and concerns.” Eva Forgacs, a scholar of Eastern Europe and a host in 2014, described her attendance at the preconference as follows, “I found it fascinating and I found that most everyone did. The diversity of the grantees was astonishing, and their respective self-introductions brought very much to the meeting. It was clear that nobody had had such opportunities of meeting colleagues from so many distant cultures and countries as we did that day.” Michele Greet, president of ALAA, who served as a host in 2016, stated simply, “Meeting these scholars was the highlight of CAA for me.” Rosemary O’Neill, who served as a host in 2013 and chaired CAA’s International Committee from 2014 to 2017, summarized the value of the hosting program this way: “Hosts enlisted to ensure CAA-Getty international scholars’ collegial welcome into the CAA academic community resulted in an important reciprocal effect. As engaged CAA members and most often members of CAA Affiliated Societies, US-based academics participating in the preconference and informal scholar-to-scholar liaising during the CAA annual conference benefited by gaining insights into their international peers’ research and methods, and communally enriching networks within and beyond CAA.” Over time, as the gap between center and periphery continues to narrow and as CAA’s international programming grows, the exchanges between hosts and CAA-Getty participants ideally will include growing numbers of American and international scholars mutually engaged in discussions, conference sessions, and online exchanges about international issues in art history.

The most sensitive questions raised by the shared work of internationalizing the field concern who gets to write about the art: Who speaks, on whose behalf, and for whom? Do art historians from North America and Western Europe have the same authority or legitimacy as scholars from Africa, Asia, or Latin America, for example, when writing about the art of these cultures? Or do scholars from Western countries inevitably reinforce a hierarchical relationship between author and subject? These concerns do not devalue the contributions made by Western scholars, but some have suggested their publications would be more accurately categorized as Western texts. These questions were also explored in an early online discussion within the context of how participants teach introductory art history. It was striking how many scholars—from Argentina, India, and Turkey, among others—rely on the Gardner, Janson, and Gombrich survey books in their classes, even if it was to ask why these books treat their countries as ancillary, if they’re mentioned at all. In large part, the answer lies in the lack of comparable texts from these countries, but it also points to the Eurocentric nature of traditional art history curriculums.

AKM Khademul Haque, from Bangladesh, was among many participants who insisted on the value of having texts by both “insiders” and “outsiders,” not only to gain the insights of multiple perspectives, but also to address the needs of different kinds of students. Four scholars from South Africa—Karen von Veh, Federico Freschi, Judy Peter, and Lize van Robbroeck—each wrote about the challenges of teaching such a traditionally Eurocentric field to students demanding the decolonization of the curriculum.

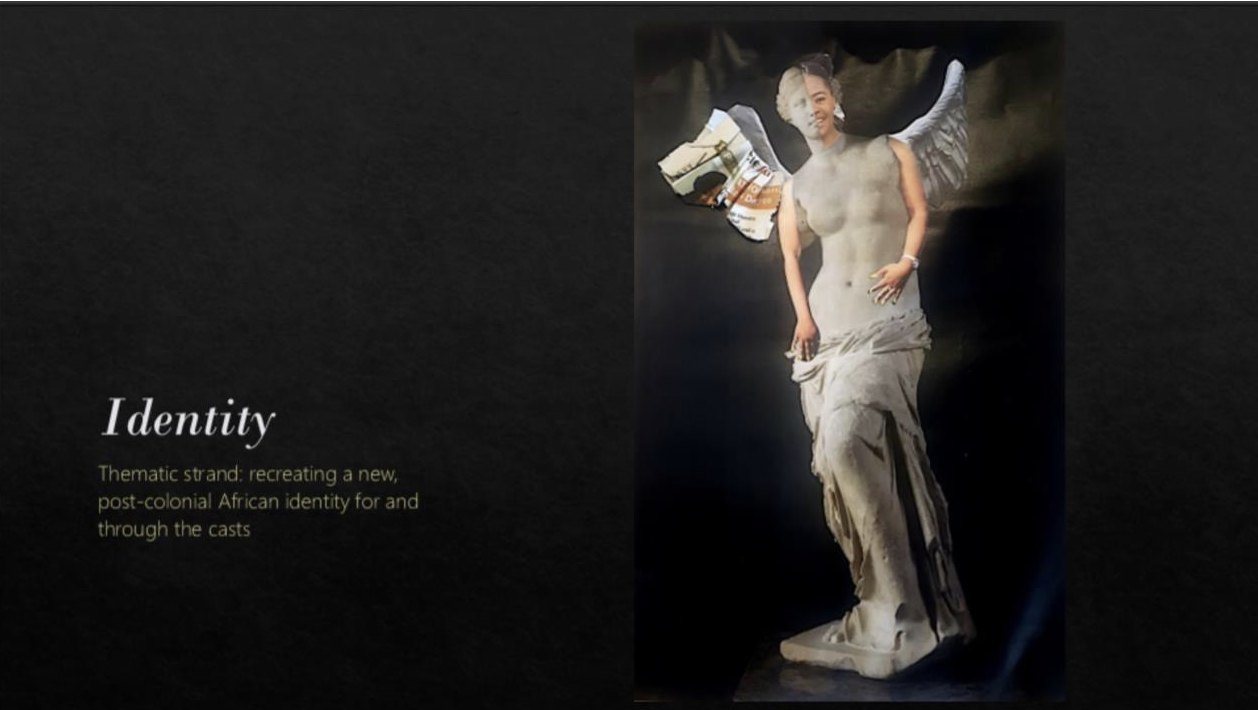

Fig. 12. Slide from “Recast: Classical Casts, the Canon, and Constructive Iconoclasm,” a paper by Federico Freschi that was part of a 2021 Global Conversations presentation. Freschi discussed an exhibition of casts at the University of Johannesburg that was organized in part to engage South African students in classical art. (photograph provided by Federico Freschi)

One solution, introduced by each of them at their universities, has been to revise courses to focus on methodologies, visual culture, or interdisciplinary content. In terms of who should be writing the texts, Peter wrote, “The impact of this intellectual protest on the teaching of art history has raised questions such as: the demography of the academics; who are the gatekeepers of new knowledge in relation to the accessibility and relevance; the perpetuation of colonial ideologies, privilege and entitlement, dissident voices and surrogate voices. . . . How do we provide a balance of global perspectives in Africa, how do we address omitted histories and narratives without producing parochial perspectives, and how do we equip students to contribute to research that is relevant outside Africa?”

Rick Asher, who was joining the online discussion as a US-based participant in the CAA-Getty program, added, “As a South Asia/Indian Ocean specialist writing from the middle of the USA, I do agree that we from the outside need to be sensitive to our foreignness, to the possibility of projecting a colonialist voice. But I also worry about limitations on who gets to speak for, let’s say, Indian or African culture. . . . If we restrict tellers of the story of art to insiders only, we risk promoting more a mythology, a canonical way of thinking, than the critical thought I think all of us hope to instill.”

Nóra Veszprémi, a Hungarian scholar now living in England, summarized the complex subject when she contributed: “The insider/outsider question is very important to me, and I thought it was worth addressing in a separate post. First of all, art history (as a humanities discipline) can never be completely objective; consequently, it can only benefit from different perspectives on the same subject. Someone who was born and raised within a culture will be aware of intricacies and hidden meanings which might escape an outsider. At the same time, the national narratives we grew up with may limit our interpretations, whereas an outsider might be able to shed new light on things simply by thinking outside that box. As others have said, the most important thing is that these two have to connect, and even intertwine, instead of existing separately in two parallel universes. . . . Switching perspectives enriches one’s scholarly thinking, and this is exactly why both insider and outsider scholarship is essential.”

Since its first conference in 2012, the CAA-Getty International Program has taken place during a tumultuous period of political, economic, and ecological upheaval throughout the world, culminating in the COVID-19 pandemic. These events have affected all of us, both in terms of personal circumstances and scholarly work. During this decade, several alumni have emigrated to other countries to find greater freedom and support for their work. Others have changed the focus of their work because of political events. One of the most affecting moments in the ten years of the CAA-Getty program occurred during the 2017 reunion Global Conversations program, when Nazar Kozak recounted the personal impact of the student protests at the Maidan in Kyiv (Kiev) in 2014, an Occupy revolution which aimed to depose the increasingly dictatorial Ukrainian president. The events, which included the killing of students by government forces, prompted a crisis of faith, as Kozak recounted in his paper, “How My Art History Was Reborn.” He recalled being part of a crowd of protesters while police attacked: “Recalling my unfinished writings on post-Byzantine iconography, I wondered―what would happen if I got a head injury and forgot everything I knew? . . . At that moment, I felt myself detached from my art history completely. Now, not only my lectures but also my writings seemed pointless. I could not think about art when people were dying on the streets.” Kozak went on to describe how he reinvented his life as a scholar, creating a community of like-minded colleagues and now including the study of art embedded in protest. (Kozak later published an expanded version of the paper in Art Journal, where it won an honorable mention for that year’s Art Journal Award.) Other political events have recurred as topics in CAA-Getty meetings, including student protests in South Africa, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the increasing strength of nationalistic movements in many parts of the world, including China, India, Poland, Hungary, Romania, and Brazil, among others.

Fig. 13. Slide from “d.o.a.,” a paper by Portia Malatjie presented in a 2017 Global Conversations reunion session. Malatjie discussed the Rhodes Must Fall student movement in South Africa. (artwork © Sethembile Msezane, published under fair use; photograph provided by Portia Malatjie)

In the United States, this decade included four years of the Trump presidency, with its destructive effects on the country’s standing in the world and, closer to home, its anti-intellectual undermining of American universities and the humanities in particular. I recall the 2017 CAA Annual Conference, which took place just a few weeks after Trump’s inauguration and his immediate imposition of an anti-Muslim travel ban. Newly arrived CAA-Getty participants—from Romania, Serbia, Ukraine, and South Africa, among others—consoled me: things would get better, we would survive.

During this period, the CAA-Getty program faced immediate difficulties obtaining visas for participants from several countries (in Africa and Eastern Europe). How could we explain to visiting scholars the growing police violence against African Americans, or the homeless people the CAA-Getty visitors saw on the streets of New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles? Can we call it a silver lining to say that this decline in American stature, which exposed the fragility of American privilege, contributed to an equalizing effect between US-based scholars and those from so-called peripheral countries? This may be an overstatement, but where things fall apart, the center cannot hold, and an unintended consequence of these circumstances may be a loosening of the center-periphery construct. Recent events have certainly affected me in this way, as the traditional hierarchies of power have begun to shift like tectonic plates beneath our feet. Most important, the instability that characterizes our time increases the importance of gathering art scholars from around the world to sustain the discipline.

In early 2020, the world shut down, fighting a global pandemic that had immediate impacts on all aspects of our lives. When the CAA Annual Conference convened in February 2020 in Chicago, the first cases of COVID-19 had just been reported in that city. The CAA-Getty International Program was already planning its tenth anniversary, to take place at the 2021 Annual Conference. By March 2020, a group of alumni had identified five topics for a series of Global Conversations conference sessions, twenty alumni had been selected to participate, and members of NCHA had agreed to serve as moderators.

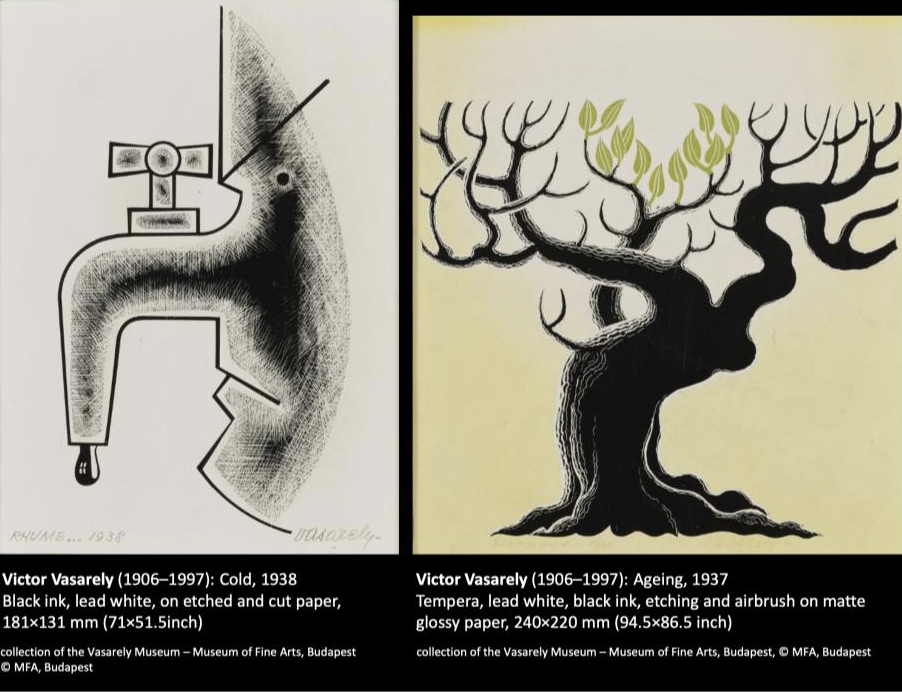

Fig. 14. One of the themes chosen for the 2021 Global Conversations reunion program was art and climate change, a topic that became more urgent during the COVID crisis. This slide is from “A Planetary Folklore against Contamination: Victor Vasarely in Cleveland,” by Márton Orosz, one of the presentations on the theme. (artworks © Vasarely Foundation, published under fair use; photographs © Vasarely Museum of the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest)

By April it became increasingly apparent that the 2021 meetings might not take place in person. Turning the crisis into an opportunity, we decided to move to a virtual format and explore the advantages of online technology for enriching international scholarly research. Between June and December, the participants met five times in small online groups to workshop their conference papers, that is, to discuss and critique each other’s work with the goal of creating fully researched and interconnected presentations. Each group identified four guest scholars (from the United States and elsewhere) to read early drafts of the papers and join in discussions of the topics. Remarkably, with new technology, real-time conversations could now take place throughout the year among people living on all continents. By the time of the 2021 virtual conference, for which each group had prerecorded its session, the benefits were evident: the six-month discussions yielded highly cohesive conference sessions and richly developed themes. (A full program and list of participants can be found in Appendix B.)

Ironically, the pandemic accelerated the realization of CAA-Getty program goals by forcing a move to a virtual format, thereby combining intensive online discussions, convened throughout the year, with fully explored international conference sessions. Georgina G. Gluzman, an alumna participant in the 2021 program, put it this way: “Personally, and without any hesitation, I think I’ve been lucky to see a glimpse of the future. The kind of work we did and how we did it (via Zoom, regularly, with only occasional technical issues) seem to me a scale model of the shape of things to come (virtual, no carbon footprint, collaborative). It was indeed a lot of work, more like a research project/collective than a mere paper: it was a process of work and emotion. And I’m happy it was like that. I feel privileged to have seen our own thinking evolve from meeting to meeting. The experience made my research better and also helped me realize that the kind of work we, as art historians, do is far from neutral and is clearly situated.”

Each year, the CAA-Getty International Program has grown organically with sustained grant support from the Getty Foundation, gradually adding annual preconferences, online written discussions, Global Conversations, and alumni advisors. What began as a straightforward travel grant program designed to bring international scholars and curators to CAA conferences has evolved into a vital annual gathering of accomplished and resourceful art historians who share a desire to be part of a global community of scholars. “A person goes on a journey, or a stranger comes to town.” “Some kind of displacement is indispensable for any creative process.” The success of the CAA-Getty International Program lies in its ongoing enactment of horizontal art history, a nonhierarchical art historical analysis on a global scale. Along the way, peripheries have been centered, centers have been questioned, and the past has been reconsidered—all essential steps toward the erasure of geographical hierarchies. It is the activity itself, the dozens of interactions among scholars across the globe, be they in person, in writing, or online, that knits together the shared enterprise of understanding art and shaping the future.