CAA News Today

International Review: A Centenary Celebration of Chilean Artist Nemesio Antúnez

posted by CAA — Nov 14, 2019

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Sophie Halart, Professor of Art History at the Universidad Adolfo Ibañez, Santiago, Chile.

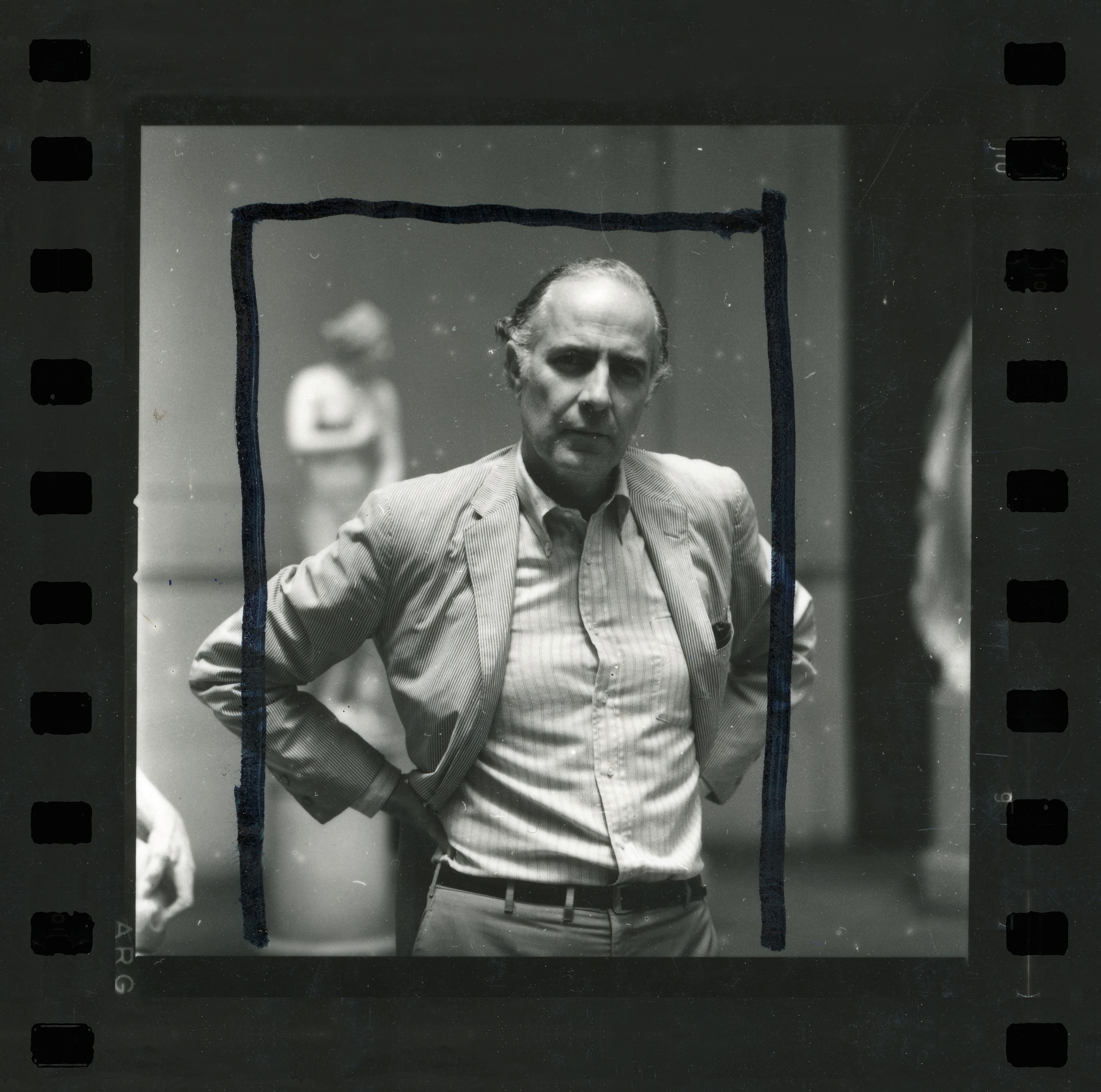

Figure 1. Promotional image of the Antúnez centenary celebration (photograph provided by the Ministerio de las culturas, las artes y el patrimonio)

In 2018-19, Chile celebrated the centenary of the visual artist, educator, and cultural figure Nemesio Antúnez (1918-93) (Fig. 1). The initiative, led by the family foundation in charge of Antúnez’s legacy, comprised several events, including roundtable discussions and archival and retrospective exhibitions throughout the country. In Santiago, the Museo de Bellas Artes (Fine Arts Museum) and the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (Museum of Contemporary Art), two institutions whose very structure and mission were profoundly modified under Antúnez’s leadership, organized a series of three exhibitions, each focusing on one aspect of his prolific career.

Figure 2. Manifiesto, installation view (photograph provided by the author)

The Museo de Bellas Artes hosted Manifiesto (Manifesto), a comprehensive retrospective of Antúnez’s artistic production (Fig. 2). Showcasing a selection of paintings, engravings, notebooks, and photographic archives, curator Ramón Castillo retraced both Antúnez’s international formation and his influence on the Chilean art scene. Initially trained as an architect in Chile, Antúnez secured a Fulbright grant in 1943 to study art in New York, where he attended Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17. Upon his return to Santiago in 1956, he founded his own engraving workshop, Taller 99, attended by important national artists like Roser Bru and Juan Downey. Antúnez’s interest in art education also led him to take part in the creation of the Universidad Católica’s School of Arts in 1959. Castillo’s exhibition offers an intimate gaze into Antúnez’s life and work, revealing the complexity of both. More importantly, the show considers the artist’s standing at the threshold of two epochs. A product of cosmopolitan modernity, Antúnez felt more acutely than most the changes that entry into the contemporary age would bring to Latin American art.

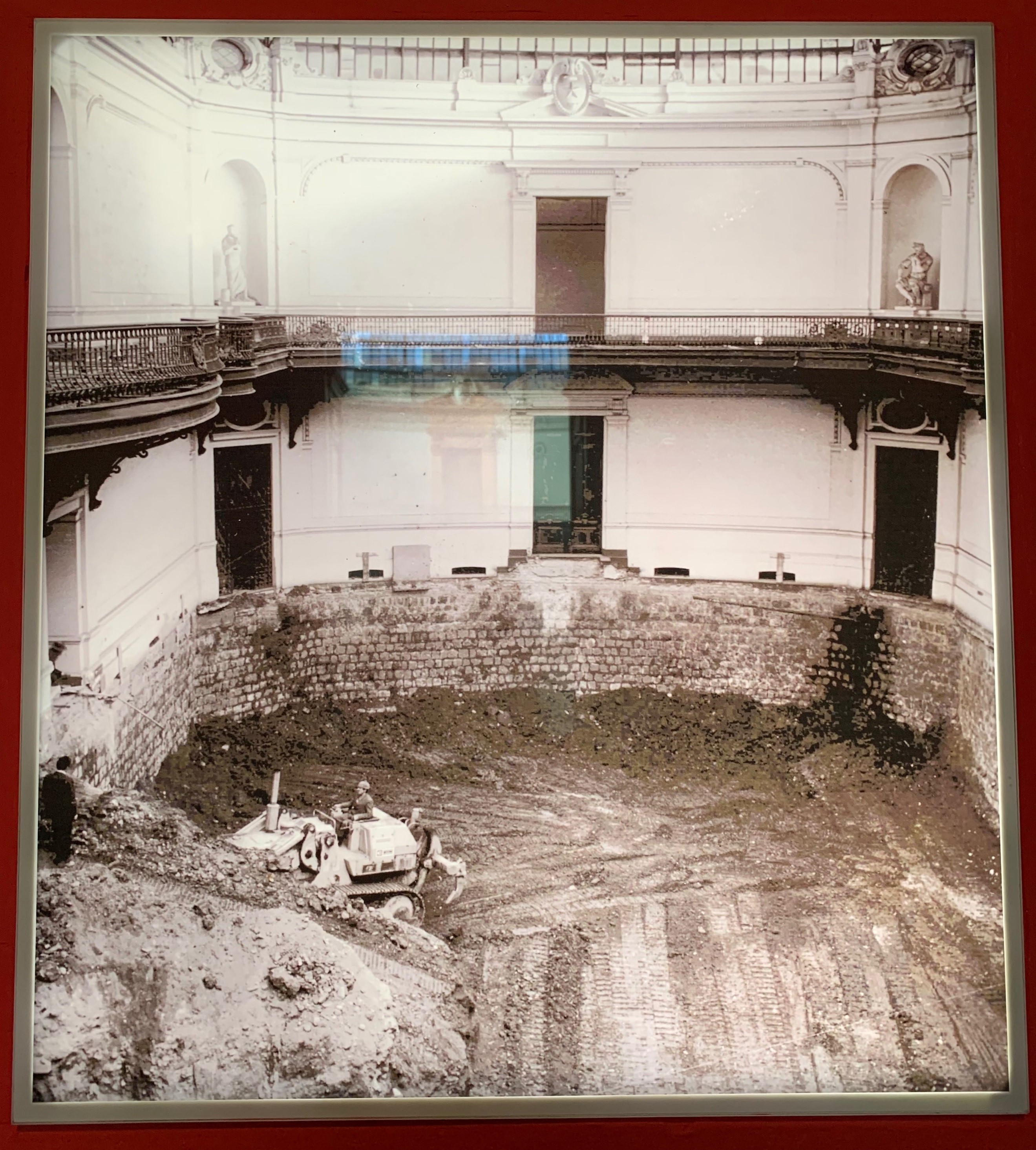

Figure 3. Construction of a lower ground floor at the Museo de Bellas Artes, Santiago (photograph provided by the author)

This temporal aspect of Antúnez is even more clearly evidenced in the second exhibition hosted by the museum. El Museo en Tiempos de Revolución (The museum in times of revolution), curated by Amalia Cross, examined the pivotal changes made by Antúnez when he became the Fine Arts Museum’s director in 1969. The appointment, which just preceded the presidential election of Socialist candidate Salvador Allende, reflected the implementation of an equally revolutionary agenda that sought to do away with the museum’s elitist image. Appealing to the etymological roots of the word museum, Antúnez opened the institution’s doors to a plurality of artistic media, including music and live performance, while striving to attract new, more diverse audiences. He also oversaw an important refurbishment of the building that included the construction of an additional, underground exhibition space dedicated to recent art (Fig. 3).

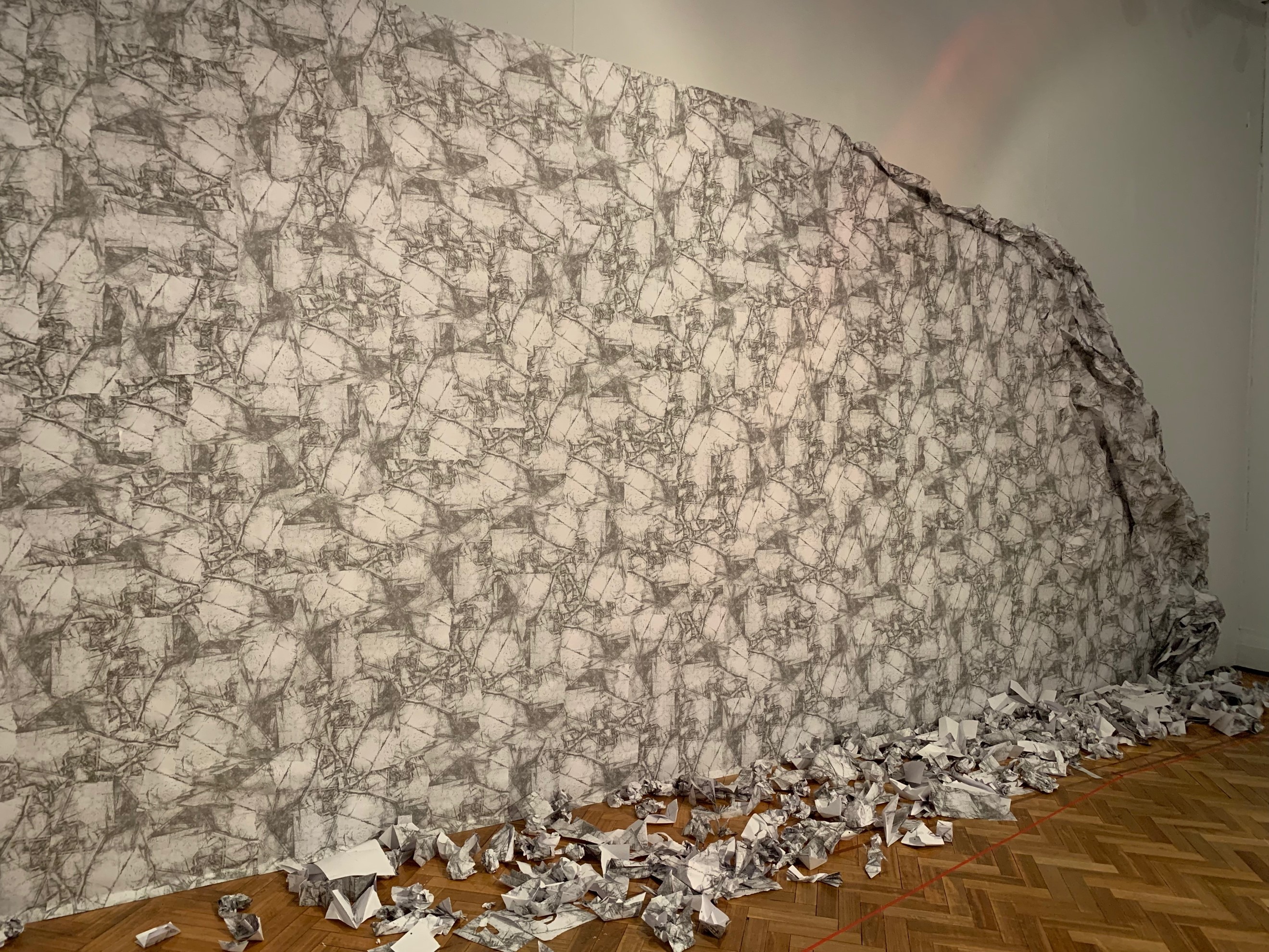

Figure 4. Liliana Porter, Wrinkle Environment, 1969. 2019 re-creation of the piece in the Museo de Bellas Artes, Santiago (photograph provided by the author)

While Antúnez shared some of the democratizing ideals of culture advocated by Allende’s government, his project to open the museum to new audiences and artistic practices—including an incipient conceptual scene—rejected strictly programmatic and propagandistic ends. Some memorable on-site interventions were performed under his tenure, including Juan Pablo Langlois’s Cuerpos Blandos (Soft bodies, 1969) and Cecilia Vicuña’s Otoño (Autumn, 1971), both pioneering the field of institutional critique in Chile. Through a display of archival documents and photographs, Cross’s curatorial work invites comparison of the infrastructural and conceptual modifications that took place in the museum. The exhibition also recreates an installation produced by Liliana Porter whom Antúnez had invited to exhibit in June 1969 along with Luis Camnitzer. A founding member of the New York Graphic Workshop (along with Camnitzer), Porter produced one of her “Wrinkled Environments,” a paper tapestry that covered the walls of the museum and which visitors were invited to modify by tearing away some of the sheets and discarding them on the floor (Fig. 4).

The 1973 military coup, which took place on the eve of an exhibition on Mexican muralism due to open a few days later, put an abrupt end to this period of political and artistic experiments and sent Antúnez into European self-exile. The return of a democratic government in 1990 allowed him to resume his work as director of the museum, a position he occupied until his death three years later.

Figure 5. Nemesio Antúnez: Panamericano, installation view (photograph provided by the author)

While these first two exhibitions focused on Antúnez during his time as director of the Bellas Artes, the show Nemesio Antúnez: Panamericano, which took place in the adjoining building of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (MAC), focused on a previous and lesser-known period of Antúnez’s professional life, namely his tenure as director of that museum (1962–64) and his influential role in rethinking contemporary artistic creation along transdisciplinary and cross-regional lines. (Fig. 5). According to the show’s curator Matías Allende, Antúnez remains a ghostly figure in the MAC, his vision haunting an institution which, when it opened in 1946, was the first museum of contemporary art in Latin America. Allende’s research focuses on the way Antúnez contributed to rethinking contemporary creation along three axes: the national, the popular, and the American. Indeed, while the off-site events he staged in modest neighborhoods of Santiago revealed an early ambition to democratize art, the organization of the first Biennial of American Printmaking (1963) showed Antúnez’s desire to build a bridge between avant-garde art and popular crafts on a continental scale. Moreover, using the connections he had made while studying in the US, his acquaintance with Alfred Barr in particular, Antúnez also piloted the organization of exhibitions comprised of works on loan from MoMA’s permanent collection. In this exhibition, Allende opted for a densely documented installation that could be overwhelming at times. Thankfully, this encyclopedic fervor was offset by the presence of short videos the curator commissioned from the video artist Flavia Contreras. Somewhat dramatizing Antúnez’s aura as an educator, these videos were fictional recreations of the cultural TV program Ojo con el arte (Watch out with the art) that Antúnez hosted for two seasons on national TV (in 1970–71 and for a second run between 1990 and 1993).

While the three exhibitions discussed above were products of independent research and curatorial planning, each of which focused on one facet of Antúnez, they may also be understood as part of a collective portrait enriching the prolific and multifarious contributions he made to Chilean art and cultural life. At the same time, the pivotal role played by the private Fundación Nemesio Antúnez in the planning of the centenary, an organization founded and directed by relatives of the artist, also begs the question of the public sector’s passivity in providing official recognition to one of Chile’s most important cultural figures. While the Fine Arts Museum, a state entity, and the MAC, a university institution that also relies on public support, did eventually take an active part in the celebration, the delays that occurred in the opening of the exhibitions were due in part to an initial lack of enthusiasm on the part of the State. Thus, while the exhibitions comprising the backbone of the centenary celebrations must be praised for their quality, they also highlight the problematic absence of public funding for culture in Chile and the ways in which the writing of art historical narratives continue to be relegated to the goodwill of private institutions and family estates.