CAA News Today

Lapsed Member? Rejoin CAA in November at 25% Off

posted by CAA — October 31, 2018

This November is the perfect time to rejoin CAA. We know your membership has lapsed, but we want you back.

We’ve just announced the full schedule for the 2019 Annual Conference in New York, February 13-16, 2019. Registration for the Annual Conference opened in October and we are on track to have our largest conference in New York in over five years. CAA just launched the application portal for the Art History Special Exhibition Travel Fund, which awards up to $10,000 to students and faculty for museum exhibition travel in connection with their studies. In the coming week, we will also release our Guidelines for Addressing Changes to Visual Arts Programs at Colleges And Universities, a new tool created in response to the many devastating arts and humanities department closures or reductions that have occurred in recent years. Be a part of the organization that supports the arts and humanities and all professionals in the field.

There has never been a better time to rejoin CAA.

We look forward to seeing you at the 107th CAA Annual Conference in New York, February 13-16, 2019.

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by CAA — October 31, 2018

Want articles like these in your inbox? Sign up: collegeart.org/newsletter

Prior to working at Penn Museum in Philadelphia, Hadi Jasim was an Iraqi translator for the US military. Credit: Courtesy of Thomas Stanley, via PRI

Experts: Federal Policy Change Would Harm Transgender Students

As the Trump administration moves to conservatively define gender under Title IX, there are implications for transgender students on college campuses. (Diverse Education)

This Philadelphia Museum Hired Iraqi and Syrian Refugees as Tour Guides for Its Middle East Gallery

“Being close to your heritage is something that makes you feel like okay, now I’m back. You know, I don’t feel like I’m a stranger [any] more.” (PRI)

Archives of American Art Announces Pivotal Gift from the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation

The $5 million gift will be put towards digitizing material on art and artists from historically underrepresented groups. (Art Fix Daily)

Professors Are the Likeliest Mentors for Students, Except Those Who Aren’t White

A recent survey shows just 47% of alumni of color said they’d had a mentor on the faculty, compared with 72% of white graduates. (Chronicle of Higher Education)

The ‘Decolonization’ of the American Museum

Museums are changing how they view themselves. (Washington Post)

A Humanities Degree Is Worth Much More Than You Realize

Enhancing the public’s understanding of how the humanities can help meet the economic, political, and technological challenges of the future is essential. (The Hill)

Paul Catanese and Greg Pond

posted by CAA — October 29, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

CAA podcasts are now on iTunes. Click here to subscribe.

This week, Paul Catanese and Greg Pond discuss intermedia pedagogy and research.

Paul Catanese is an associate professor at Columbia College Chicago where he directs the graduate program for the Art and Art History Department; he’s been known to fly kites, launch rockets, pilot drones, and lately a blimp as part of his art practice.

Greg Pond is professor of art at Sewanee: The University of the South in Tennessee. Originally from Portland, Oregon, Pond is one of the founder’s of Nashville’s Fugitive Projects and a sculptor who incorporates sound, video, and digital media into his practice and also makes documentaries about social justice issues in inner city Kingston, Jamaica.

New in caa.reviews

posted by CAA — October 26, 2018

Joanne Allen reviews The Medieval Salento: Art and Identity in Southern Italy by Linda Safran. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Blake Stimson writes about Revoliutsiia! Demonstratsiia! Soviet Art Put to the Test, edited by Matthew S. Witkovsky and Devin Fore. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Shira Brisman discusses Animating Empire: Automata, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Early Modern World by Jessica Keating. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Rebecca Corbett explores Around Chigusa: Tea and the Arts of Sixteenth-Century Japan, edited by Dora C. Y. Ching, Louise Allison Cort, and Andrew M. Watsky. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Nicholas Miller writes about Archibald Motley Jr. and Racial Reinvention: The Old Negro in New Negro Art by Phoebe Wolfskill. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

International Review: L’Algérie de Gustave Guillaumet by Roger Benjamin

posted by CAA — October 26, 2018

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Roger Benjamin, professor of art history, University of Sydney, Australia.

Exhibition review: L’Algérie de Gustave Guillaumet (1840-1887), Musée des Beaux-Arts de La Rochelle (France), June 8-September 17, 2018

In a most unassuming regional museum in France, an exhibition of real art-historical significance opened this past June. For the first time since 1899, the work of the preeminent French Orientalist painter of the later 19th century has been brought together. Gustave Guillaumet is not an obscure artist, as every survey of Orientalism since the great Royal Academy show of 1984 has included his paintings. But the scholarly work had not been done until now, when the fruits of Marie Gautheron’s 2015 doctoral dissertation on the desert and Guillaumet have been brought to bear (Gautheron, M., L’invention du désert: émergence d’un paysage, du début du XIXe siècle au premier atelier algérien de Gustave Guillaumet (1863-1869), Paris Nanterre University).

Fig. 1. Gustave Guillaumet, La Famine en Algérie, Salon of 1869, oil on canvas, 122 x 92 in (309 x 234 cm) Le Musée National Public Cirta de Constantine, Algeria (restored for the exhibition).

Many of the works on view in La Rochelle are unfamiliar, coming from regional museums, the artist’s descendants, private enthusiasts, and storage collections of the Musée d’Orsay. The largest single work was thought to have been lost. The Famine in Algeria (Fig. 1), the most disturbing large scale canvas at the Salon of 1869, was known only by a poor woodcut and several drawings. Its subject was altogether too tough—the cadaverous members of two Arab families expiring on the pavement of a city in what was (in French law) a department of France, the province of Algiers in Algeria.

La Famine had been languishing, rolled up and torn in the basement of the National Public Museum of Constantine, Algeria (Le Musée National Public Cirta de Constantine). The research of Dr. Gautheron located it, and through the goodwill of Algerian curators and the political weight of Maître Salim Becha (an Algiers-based lawyer, art collector and philanthropist) the work was sent to France for restoration. A successful crowd-funding campaign led by Annick Notter, chief curator at La Rochelle, paid for the conservator Pascale Brenelli, who spent nine hours every day from early February until mid-June resurrecting the picture.

Guillaumet’s ghastly image of a baby suckling at the collapsed breast of its dead mother goes back through Eugène Delacroix to Nicolas Poussin and classical precedents. Entirely new, however, is his angular figure of an emaciated Arab father who, supporting his fainting teenage son, reaches up for a loaf of bread being handed down from the tiny window of a prosperous home. The outstretched hand is female, bejeweled and, through the curvature of its fingers, evocative of the Jewish beauties painted by Chasseriau in Constantine (1846) and by Delacroix in Tangier (1832).

La Famine’s grisly treatment was probably influenced by photographs of the dying taken in situ. Catalogue author (and leading historian) Jacques Frémaux estimates one third of the indigenous population of Algeria died in the famine of 1866-70, due to drought, locust plague, cholera, and the expropriation of farmlands by European settlers. La famine is unrelieved by aesthetic ‘sweet spots’ like the majestic horseman that Delacroix placed in his Massacres of Chios. We have instead the moral and visual austerity that pervades Guillaumet’s work. A grave witness to these events, Guillaumet was not about to beautify them.

Fig. 2. Gustave Guillaumet, La Séguia, près de Biskra, oil on canvas, 1884, Salon of 1885, 39 x 61 in (100 x 155.5 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Almost all of the artist’s best-known landscapes are on view, including The Sahara of 1867, with its camel skeleton and mirage at the horizon with a setting sun, and the dazzling Séguia, Biskra (Fig. 2) of 1884. (Both are usually on display at the Musée d’Orsay). The loan of numerous restored pencil drawings and watercolors from the Orsay was intended to show the genetic relationship between such studies and the resultant tableaux by Guillaumet (who narrowly missed the Prix de Rome for landscape and ended up heading to Algiers in 1862 rather than Rome). (Fig. 3)

It came as a shock to learn that many of these drawings could not be exhibited on the second floor of the eighteenth-century mansion that houses the Musée de la Rochelle, as it was condemned by city architects one week before the scheduled opening. Despite the best efforts of the staff, this major exhibition was opened in almost third world conditions: a building with the floor above held up by a dozen massive steel columns, no air conditioning, and inadequate spotlighting. Yet historic La Rochelle is a wealthy city, with a new 5,000-boat marina and an opulent public library, the Mediathèque, nearby. City and provincial authorities must reward the enterprise of its art curators by providing an adequate home for future temporary exhibitions and permanent collections.

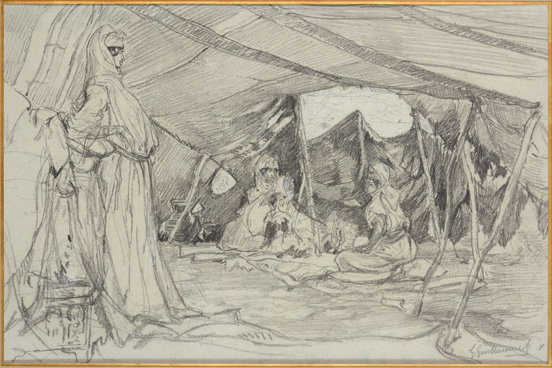

Fig. 3. Gustave Guillaumet, Sous la tente, graphite pencil on paper, 9.5 x 17 in (24 x 44 cm), private collection. Photo: A. Leprince.

Fortunately, L’Algérie de Gustave Guillaumet will travel to two other regional museums in much better condition: the Limoges Fine Arts Museum and the celebrated La Piscine, a converted Art Nouveau baths complex in the northern city of Roubaix. And happily, the catalogue, a scholarly book with first-class production values and superb plates, perfectly represents the project. Its backbone is the set of four chapters by Gautheron, a former academic teaching art history and visual culture at the École normale supérieur de Lyon, along with detailed entries on key works and a documentary apparatus at the end. Gautheron was careful to enlist a range of other writers, including Algerian literary figures like Leïla Sebbar, and art historians from Algeria, the United States, Australia, France, and Ireland. For her part Gautheron has also completed a 300-page monograph on Guillaumet that is awaiting publication.

Fig. 4. Gustave Guillaumet, Habitation saharienne (Cercle de Biskra), Salon of 1882, oil on canvas, 58 x 68 in (146.1 x 173.4 cm), Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia, gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr.

Guillaumet, like the admirable Eugène Fromentin before him, traveled initially in Algeria in close connection with the officers of the French army and its political wing, the Bureau Arabe. His stunning series of interiors of Arab houses, made in the oasis villages of Biskra and Bou-Saâda, were made possible by the intervention of the Commandant’s wife (as the artist narrates in his text “Les intérieurs,” from his book Tableaux Algériens). Crowning the series but absent from the exhibition was the key Guillaumet work in America, Saharan Dwelling (Fig. 4), recently loaned by the Chrysler Museum of Norfolk Virginia to the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris (see the author’s Biskra, Sortilèges d’une oasis, Paris and Algiers, 2016, pp. 90-91). Scenes of women and their daughters working at looms, the first of their kind and highly influential on the next generation, complement Guillaumet’s earlier assemblages of men, camels and horses on the barren plains—at prayer, at market, or on a military bivouac. Guillaumet, an admirer of J. F. Millet, produces high naturalism, except in one key respect: he always excludes the colonizer and his works. Absent are the soldiers in uniform, colonists directing Berber farmworkers, the modern buildings and telegraph wires at Bou-Saâda, the military hospital at Biskra where the painter convalesced in 1862, or the British tourists who by the 1880s were encumbering the desert scene. Guillaumet’s vision is not a “painting of modern life” as exemplified by the traveler Constantin Guys in Istanbul. It is an image of Algeria as it used to be: a country and a people that won the admiration of foreign travelers, intellectuals and officers, even as their invasive actions helped bring about its demise.

Member Spotlight: Pauline Chakmakjian, Visit Kyoto Ambassador

posted by CAA — October 25, 2018

Lanterns lit in Teramachi Street, Kyoto. Photo: Pauline Chakmakjian, MA

Coming up in the spring of next year, we’re pleased to partner with Martin Randall Travel to offer a trip for scholars and artists to Japan. “Understanding Japan for CAA – Arts & Crafts, History, Religion & Traditions” will take place May 9-20, 2019, and will be led by independent Japan scholar and CAA lifetime member, Pauline Chakmakjian.

As a lifetime member and a specialist who lectures on a variety of subjects related to the history, fine arts, and culture of Japan, we wanted to highlight the work Pauline is doing in our Member Spotlight series. Read our interview with her below.

Pauline Chakmakjian, Freeman of the City of London, September 2018. Photo: Pauline Chakmakjian, MA

Joelle Te Paske: Hi Pauline. Thanks for taking the time to answer our questions. So to begin, where are you from originally?

Pauline Chakmakjian: I was born in Los Angeles, California.

JTP: What pathways led you to the work you do now?

PC: My primary passions are travel and the arts. The associations and networks I have developed throughout the years have naturally led to projects that combine this fondness for both cultural variety and the diversity of thought and creativity in various countries, especially Japan.

Temple in Kyoto. Photo: Pauline Chakmakjian, MA

JTP: When did you first become a CAA member?

PC: In the summer of 2015, in order to support art and art education.

JTP: Why are you a life member? What has that meant to you?

PC: I think in a long-term manner and carefully select organizations to support that reflect my own interests. With time, becoming a life member will increase in value for me personally, since CAA is focused on art and art makes life exceptionally rich and pleasant. My preference is to support things that encourage creativity and beauty—arts and culture are what makes us human.

JTP: Have you attended CAA conferences?

PC: I have not yet had the pleasure of attending a CAA conference due to my previous travel commitments, but certainly plan to in the future.

JTP: The upcoming tour—“Understanding Japan for CAA – Arts & Crafts, History, Religion & Traditions”—is specifically designed for CAA members. What are you most excited for?

PC: The Kyoto part of the trip, which is towards the end of the tour, of course! In so many ways, the old capital of Kyoto is the heart of Japan, from artistic and culinary traditions that are over one thousand years old, to the eternal backdrop of the tastes and pastimes of the nobility of the Heian-period court, which have cascaded down to influence generations of Japanese people ever since.

JTP: What is the most surprising thing for people to know about Japanese art history?

PC: There are many surprises for those who have never been to Japan or studied its artistic heritage, but if I had to choose one it would be that much of the traditional look or aesthetics of Japanese art are manifestations of the preferences of the upper tiers of the hierarchical class system the Heian court of one thousand years ago, borrowed from the ancient Imperial Chinese court in Chang’an (Xian). The upper two tiers consisted of the Emperor and his retinue of courtiers first, and then the warrior class. These two classes were largely responsible for the distinctive elements and emphases found in Japanese art, from landscape architecture to painting to teaware.

Doll of Lady Murasaki Shikibu, Kyoto. Photo: Pauline Chakmakjian, MA

JTP: Can you tell our members one unforgettable travel story?

PC: Yes, sailing to Easter Island was probably the most adventurous thing I’ve attempted travel-wise. From Tauranga to Hanga Roa I was on board a two-masted brigantine with a permanent and voyage crew for 33 days of sailing across the Pacific. I had always wanted to visit Easter Island and this travel journey combined this dream with my love of classical sailing ships. We were also given instruction on celestial navigation over the course of the sailing experience.

The image that stays in one’s mind and feeling of sailing through a gale force 8 storm at the helm is thrilling. I love paintings by Montague Dawson and this was like one of his paintings in motion.

Montague Dawson, A Night at Sea, n.d. (Artwork in the public domain, via Flickr)

JTP: What advice would you give someone looking to partner with travel agencies and lead the sort of tours you do?

PC: A broad range of knowledge on the destination is essential. Though the focus is usually on the arts in terms of cultural travel companies, the tour leader will be asked about the other aspects of the country such as its politics, economy, technology, and other areas, so it’s not enough to simply know about fine art, music, and the performing arts.

Heian Shrine, Kyoto. Photo: Pauline Chakmakjian, MA

JTP: What is your top recommendation (such as a book, website, or resource) for people working in the arts right now?

PC: There are so many resources both offline and online depending on one’s particular focus or interest in the arts, but I do quite like the international edition of The Art Newspaper. It’s particularly handy for people who travel a lot.

JTP: Do you have a favorite artist or artwork?

PC: This is difficult to answer as there are so many talented people who have created beauty of various types in this world, but the moment that made me want to lecture on art was during my undergraduate studies after I gave a talk for over an hour on The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymous Bosch. This triptych is truly one of the most unique and extraordinary works of art ever made. The eccentricities within each section of the triptych as well as Bosch’s personal associations is what also partly made me curious about private, esoteric networks such as Freemasonry, which I also lecture on.

Pauline Chakmakjian is an independent lecturer on a variety of subjects related to the history, fine arts and culture of Japan. She lectures for private member societies, corporate entertainment, private homes, universities, cruises, charities and other related organizations including lecture tours in Australia and New Zealand. She holds a BA in English Literature during which she was also awarded a Merit Scholarship in Fine Art, a Diploma in Law, an MA in Modern French Studies and is a member of the Honourable Society of the Inner Temple. Pauline was elected onto the Board of the Japan Society of the United Kingdom from 2008–2014 and the Japan Society of Hawaii from 2015–2017. In 2014, Pauline was appointed a Visit Kyoto Ambassador by the Mayor of the City of Kyoto.

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by CAA — October 24, 2018

Want articles like these in your inbox? Sign up: collegeart.org/newsletter

Taco Dibbits, the Rijksmuseum director, viewing the Night Watch. The work, by Rembrandt, will be restored in what Mr. Dibbits called the museum’s “biggest conservation and research project ever.” Credit: Rijksmuseum/Kelly Schenk via The New York Times

The Met and Brooklyn Museum Opt to Reject Saudi Funds

As the international outcry over the fate of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi grows, ripple effects have reached the art world. (artnet News)

The Lawsuit Against Harvard That Could Change Affirmative Action in College Admissions, Explained

The trial is being closely watched for signs about the future of admissions processes across the country. (Vox)

‘Not Everything Was Looted’: British Museum to Fight Critics

The museum has faced criticism for displaying―and refusing to return―looted treasures, including the Parthenon Marbles, Rosetta Stone, and the Gweagal shield. (The Guardian)

Doctors Can Soon Prescribe Visits to Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

The museum says the one-year pilot project is the first such initiative in the world. (Montreal Gazette)

Rembrandt’s ‘Night Watch’ to Undergo Years of Restoration

The painting will remain on display so the public can observe the process. (New York Times)

How to Be Strategic on the Tenure Track

So how do you resist overworking when, in many instances, that seems the only path to tenure? (Chronicle of Higher Education)

Annual Conference Committee Chair Charlene Villaseñor Black on Why You Can’t Miss CAA 2019

posted by CAA — October 23, 2018

Charlene Villaseñor Black is Professor of Art History and Chicana/o Studies at UCLA and chair of the Annual Conference Committee for the 2019 Annual Conference in New York, February 13-16, 2019.

As a crucial player in the conference process, we asked Charlene to share her thoughts on the field, being a part of CAA, and what goes into making the conference a reality every year. Listen in or read her thoughts below.

So, chairing the Conference Committee is a huge job. We had a record number of submissions—there was a lot of reading—but it was also very exciting to see where our members are, and what kinds of things people are doing in terms of their artistic practice, what things art historians are thinking of. It was actually very exhilarating to read these submissions.

When I came on, agreed to do this, I had a couple of goals in mind, and the first one for me was diversifying CAA. Really broadening out what kinds of topics we were looking at. I was also interested in pulling in more people who are working on historic time periods. I’m someone who works on colonial, on early modern but I also work in contemporary Chicanx art. So I’m very much interested in seeing how differing fields can speak to each other, and I was also very much interested in studio art, and a little nervous about that because I actually think that dialogue with artists is extremely important for those of us who are historians.

The submissions that we read were very exciting. There are many different themes, a very diverse representation of subject areas. What was interesting to me was that several themes that transcend chronology or geography came out to me. There were a lot of panels on the politics of artistic production. There were a lot of panels looking at migration, immigration, globalism. There were a lot of panels looking at the environment, artistic practice in the environment. Materiality was another very important topic that I saw that’s still very popular.

So I was very attentive to the representation of historical panels for the annual conference. This is actually very important to me, and there were a lot of early modern panels. As someone who works on early modern colonial and contemporary, I really think about why history matters. And in this current political moment, I think we understand why history matters, and why facts matter. And thinking about the current migration crises in the world right now, the roots of those crises are really in the early modern period, during this period of European imperialism. So I actually think this is a moment when we can really speak to each other across time periods, across fields. It’s a really important moment for us to do that.

I hope that the biggest surprise about the conference is its incredible breadth, and the incredible range of interests that our members have, and people are working on in their studio practices, in their scholarship.

My very first CAA was in 1992. I was a graduate student. It was in Chicago, and I very clearly remember going to that first conference. I felt intimidated. I also remember very well, I think it was 1995, San Antonio. I was on the job market, but what I remember is that there were two Latin American panels. There were two colonial panels. They were scheduled at the same time unfortunately, but I remember presenting at that conference.

CAA is the major professional organization that I belong to. I’m also active in Latinx studies, but CAA for me feels like home. I was very fortunate to win one of the CAA Millard Meiss subventions early on for my first book. CAA to me is just fundamental in terms of you go to the conference, you see what everyone’s working on, what does the field look like at this moment? You see lots of old friends. You hopefully meet some new people.

The job market is a challenge right now for young scholars who are just finishing. Because of the fields I work in, I am very fortunate that my students have done really well. They tend to have multiple job offers. I had two people on the market this year, so I’m very grateful for that. I think it’s actually really important to broaden what it is we can teach and what we can talk about. Not just be highly specialized in twenty years of the 16th century, for example. It’s extremely important to have range, to be able to even move out of art history. A number of my students are also working in ethnic studies right now, and they’ve all done beautifully on the job market.

I think it’s also up to us to argue for the importance of what we do. Visual literacy could not be more important than it is at this particular moment. This is the most visual world that has ever existed, so that visual literacy argument is important for us to make, I feel.

So we had a record number of submissions this year, and I read a lot of them. I read hundreds of the submissions, and really allotted a lot of time to doing it, because you want to make sure you give every submission a fair read and a good read. You don’t want to be grouchy or tired when you’re reading someone’s submission. It’s their work. It’s very important. So I read I’m guessing 400 or 500 of the submissions. Yeah. I really wanted to get a sense of where everybody was.

The final decisions are made by a committee, by the Annual Conference Committee, and there were so many submissions this year that we pulled in extra readers. You want to have a very diverse group of readers because our knowledge tends to be very particular. For example, you want to make sure you have people who are in studio art reading studio art proposals. Somebody who understands maybe contemporary may not understand ancient pre-Columbian. So you want to have readers who are literate in a variety of areas able to read and fairly assess the submissions.

I think it’s really important, and I’m speaking as an advisor, as a mentor, as someone who’s also an editor, that I like it when we put our main idea out first or upfront. When we’re talking in a proposal submission, I think it’s important to not kind of unroll your way to the main point. So I think being direct can really help clarify what you’re talking about.

I think to be successful presenting, it is really important that you’re not just reading, looking down, reading your script. That even if you have to rehearse moments of engagement with the audience, that will really enliven the presentation. Take time to look at the images you’re talking about, to point out things in the images. Take time to engage directly with your audience, make eye contact with them. I know when I’m working with students, it’s very important to tell people that you need to do those things, and to rehearse the paper so that you’re not stumbling—you know what you’re going to say before you say it.

I love the opportunity to connect with people that I haven’t seen since the last conference. I love seeing the latest work that’s happening in art history, and I love hearing artists talk about what they’re doing.

Charlene Villaseñor Black, whose research focuses on the art of the Ibero-American world, is Professor of Art History and Chicana/o Studies at UCLA. Winner of the 2016 Gold Shield Faculty Prize and author of the prize-winning and widely-reviewed 2006 book, Creating the Cult of St. Joseph: Art and Gender in the Spanish Empire, she is finishing her second monograph, Transforming Saints: Women, Art, and Conversion in Mexico and Spain, 1521-1800. Her edited book, Chicana/o Art: Tradition and Transformation, was released in February 2015. She is co-editor of a special edition of The Journal of Interdisciplinary History entitled Trade Networks and Materiality: Art in the Age of Global Encounters, 1492-1800, with Dr. Maite Álvarez of the J. Paul Getty Museum; and editor of a forthcoming issue of Aztlán focused on teaching Chicana/o and Latina/o art history. She has held grants from the Getty, ACLS, Fulbright, Mellon, Woodrow Wilson Foundations and the NEH. While much of her research investigates the politics of religious art and global exchange, Villaseñor Black is also actively engaged in the Chicana/o art scene. Her upbringing as a working class, Catholic Chicana/o from Arizona forged her identity as a border-crossing early modernist and inspirational teacher.

Join a Jury for CAA Professional Development Fellowships

posted by CAA — October 23, 2018

The CAA Professional Development Fellowships in Visual Art and Art History jury is currently looking for members.

The deadline is October 26, 2018.

CAA Professional Development Fellowships in Visual Art and Art History

The fellowship juries award $10,000 each to one visual artist completing an MFA and one art historian completing a PhD in the coming year. There are currently two vacancies on the jury awarding the fellowship in art history and three vacancies on the jury awarding the fellowship in visual art. Candidates for the art history jury must be actively publishing scholars with demonstrated seniority and achievement; candidates for the visual arts jury must be actively producing artists with a track record of exhibitions. Institutional affiliation is not required.

Jury members review applications once per year and confer by conference call. All jurors serve for a three-year term. Candidates must be CAA members and should not currently serve on another CAA editorial board or committee. CAA’s president and vice president for committees appoint jury members for service. Jury members may not themselves apply for a grant in this program during their term of service. This is a volunteer position without compensation.

Nominators should ascertain their nominee’s willingness to serve before submitting a name; self-nominations are also welcome.

Please send a letter describing your interest in and qualifications for appointment, along with a CV (two pages maximum) to nyoffice@collegeart.org.

Explore the Latest Issue of The Art Bulletin

posted by CAA — October 22, 2018

Print copies have been shipped. Click here to explore the digital version.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Touch and Remembrance in Greek Funerary Art

Nathan T. Arrington

Iconoclasm’s Legacy: Interpreting the Trier Ivory

Paroma Chatterjee

Ingenuity in Nuremberg: Dürer and Stabius’s Instrument Prints

Alexander Marr

Portrait of a Renaissance Dwarf: Bronzino, Morgante, and the Accademia Fiorentina

Robin O’Bryan

Decolonizing Modernism: Robert Henri’s Portraits of the Tewa Pueblo Peoples

Allan Antliff

REVIEWS: Antiquities and Heritage

Marisa Anne Bass, Jan Gossart and the Invention of Netherlandish Antiquity

Stephanie Porras

Peter N. Miller, History and Its Objects: Antiquarianism and Material Culture since 1500

Ulf R. Hansson

Zeynep Çelik, About Antiquities: Politics of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire

Frederick N. Bohrer

Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Building Histories: The Archival and Affective Lives of Five Monuments in Modern Delhi

Santhi Kavuri-Bauer

Not a member? Click here to join CAA and explore the issue in full.