CAA News Today

caa.reviews Seeks Field Editors for Books and Exhibitions

posted by Christopher Howard — October 31, 2016

caa.reviews invites nominations and self-nominations for individuals to join its Council of Field Editors, which commissions reviews within an area of expertise or geographic region, for a term ending June 30, 2019. An online journal, caa.reviews is devoted to the peer review of books, museum exhibitions, and projects relevant to art history, visual studies, and the arts.

The journal seeks field editors to commission reviews of books in museum studies and of exhibitions on the West Coast, in the Midwest, and in Europe. Candidates may be artists, art or design historians, critics, curators, or other professionals in the visual arts; institutional affiliation is not required.

Field editors select content to be reviewed, commissions reviewers, and reviews manuscripts for publication, working with the journal’s editor-in-chief, editorial board, and CAA staff editor as necessary. Field editors for books are expected to keep abreast of newly published and important books and related media in their fields of expertise, and field editors for exhibitions should be aware of current and upcoming exhibitions (and other related projects) in their geographic regions. The Council of Field Editors meets annually at the CAA Annual Conference.

Candidates must be current CAA members and should not serve concurrently on the editorial board of a competitive journal or on another CAA editorial board or committee. Nominators should ascertain their nominee’s willingness to serve before submitting a name; self-nominations are also welcome. Please send a statement describing your interest in and qualifications for appointment, a CV, and your contact information to: caa.reviews Editorial Board, College Art Association, 50 Broadway, 21st Floor, New York, NY 10004; or email the documents to Deidre Thompson, CAA publications assistant. Deadline: January 15, 2017.

New in caa.reviews

posted by CAA — October 28, 2016

Hollis Clayson reads The Work of Art: Plein-air Painting and Artistic Identity in Nineteenth-Century France by Anthea Callen. The “impressive book, chockablock with technical information,” views “the visible painted mark” as not only an “index of an artist’s working methods and tools, but also the inescapable sign of the painter’s aesthetic, social, and institutional allegiances.” Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Claire Grace discusses Taryn Simon: Paperwork and the Will of Capital, an exhibition hosted at Gagosian Gallery, New York. Grace focuses on twelve sculptures that feature plant specimens yet spring “from the world of geopolitics and trade.” Although sculpture “is a departure for Simon,” the series “extends the research-driven, post-documentary axis of her photography-based practice.” Read the full review at caa.reviews.

James Housefield reviews Ruth E. Iskin’s The Poster: Art, Advertising, Design, and Collecting, 1860s–1900s. This “engaging and readable book” “rethinks the role of print media in the creation and transformations of modern art.” Arguing “persuasively for renewed examination of posters” in visual culture, the volume “contributes to the history of modern art, writ large.” Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Jessica N. Richardson examines From Giotto to Botticelli: The Artistic Patronage of the Humiliati in Florence by Julia I. Miller and Laurie Taylor-Mitchell. “A long-awaited study,” the book “traces the entire span of Humiliati art at a single location.” It “provides another model for breaking down period boundaries and envisaging images and objects as communicating through the centuries.” Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Caa.reviews publishes over 150 reviews each year. Founded in 1998, the site publishes timely scholarly and critical reviews of studies and projects in all areas and periods of art history, visual studies, and the fine arts, providing peer review for the disciplines served by the College Art Association. Publications and projects reviewed include books, articles, exhibitions, conferences, digital scholarship, and other works as appropriate. Read more reviews at caa.reviews.

Staff Interview: Paul Skiff

posted by CAA — October 27, 2016

Paul Skiff

Paul SkiffAs part of the new myCAA campaign where we ask our members to share with us what CAA means to them, we thought it also makes sense to share with our members more about ourselves at CAA. In this spirit, every few weeks we will post an interview with a staff member at CAA. We want our members to know who we are also.

Our first interview in the series is with Paul Skiff, assistant director for Annual Conference.

How long have you worked at CAA?

Seventeen years.

What do you do at CAA?

I handle all space use for the Annual Conference: facility specification and coordinating with facility personnel, logistics, service providers, production, marketing, and sponsorships for the Book and Trade Fair, receptions, tours, onsite direction, and the task of working up budgets for all of this. Essentially I set up the arrangements that enable us at CAA to coordinate everyone and everything into and out of the conference.

What does CAA mean to you?

CAA is a leading international organization promoting visual art and culture in a way that has direct impact on society. The conference brings together the membership, along with related professions, for a large public event that gives a high profile to the cultural sector of the host city and contributes to defining the forward direction of culture in general.

Can you talk about one of your favorite member moments?

Too many to mention, really. CAA members are so frequently a great pleasure to work with no matter what the situation. At its base the organization is a collective, and that really guides so much of what members bring.

What do you like best about the arts and working in the arts?

Art, and culture in general, provides a basis for unity across social, cultural, national, and political boundaries. In the urban culture of the United States, cultural practice is seen as an open forum with authority to comment upon—and provide a way for coping with—the prevailing conditions of the time. Applied this way, cultural practices have as their main goal establishment of a democratizing equality. What I like about one part of the particular work I do in the arts with CAA is that my efforts serve to create opportunities for thousands of people involved in art and culture. Over my time working with CAA, this has amounted to providing a wide variety of opportunities for literally tens of thousands of people involved with art and culture.

Do you have a favorite moment from the Annual Conference each year?

The closing celebration for department staff after sessions conclude on the last day of the conference, when a year’s worth of hard work is complete and you know thousands of people had a pleasurable and fulfilling experience.

Video capture of Paul Skiff’s performance Blood Circle

Video capture of Paul Skiff’s performance Blood CircleWhat have your most recent performances consisted of?

My most recent performances have been straightforward presentations of texts and poetry spoken live, often with supplemental sound, and mostly presented for community-based cultural organizations with a vision for preserving, promoting, and strengthening local culture.

How do you feel about the differences between your art performed live or recorded on tape?

My live performance often incorporates recorded sound and images, so it is not that easy to separate the two modes of presentation. But to consider electronically recorded material separately, there is of course a vast difference with regard to the resultant sensory phenomenon. The main strength of actual live, spoken work is its generative quality, its immediacy, and its ability to create a “hearership” that can challenge existing listening institutions. With electronically recorded sound and/or images you have the rather endlessly deep toolbox of technology, which mostly amounts to applying exaggeration and distortion to live forms, and playing with time, as well as simply preserving information for transmission. I’m not saying anything profound by that, of course. Applying technology to a live performance enables an extension and transformation of form that allows for many different and new ways to present the work, seek a broader audience, and invent ever more creative solutions.

The creation of electronic information along with storage and retrieval is the most expansive creative environment for us now. At this point in our history telelectricentrism is second nature. Humanity has adapted to this so that forms of experience based on electronic image and sound increasingly dominate everyday life. We are still discovering how this is an asset and liability. It has mixed results and risky implications for our ability to really communicate. But in this for me is a great and absorbing task of applying these distorting and exaggerating technologies to instill acts of rehumanizing our culture. It’s kind of like taking something inherently dangerous and reshaping or repurposing it to provide pleasure, fulfillment, and a greater sense of shared well-being—not to mention preserving and strengthening our sense of self-worth.

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by Christopher Howard — October 26, 2016

Each week CAA News summarizes eight articles, published around the web, that CAA members may find interesting and useful in their professional and creative lives.

Doubts about Date: 2016 Survey of Faculty Attitudes of Technology

Most faculty members say data-driven assessments and accountability efforts aren’t helping them improve the quality of teaching and learning at their colleges and universities, according to the 2016 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology. Instead, instructors and many academic technology administrators say the efforts are mainly designed to satisfy accreditors and politicians. (Read more from Inside Higher Ed.)

The Next Step in Diversifying the Faculty

These days there’s no escaping discussions about the need to diversify academe. So it should be. A recent addition to this brimming conversation was a widely discussed essay in The Hechinger Report from Marybeth Gasman, in which she argued that there aren’t more people of color on faculties for a simple reason: colleges and universities don’t want them. (Read more from the Chronicle of Higher Education.)

After a Decade of Growth, MFA Enrollment Is Dropping

Across the country, art schools have minted a growing number of visual art MFA programs over the last ten to fifteen years. Many of them now face a challenge, as application numbers and enrollment figures are falling, according to the better part of a dozen insiders who spoke to Artnet News, some of them on condition of anonymity. (Read more from Artnet News.)

David Salle’s How to See, a Painter’s Guide to Looking at and Discussing Art

The painter David Salle, in his new book How to See: Looking, Talking, and Thinking about Art, goes bravely in search of happiness. His quarry is aesthetic bliss. Salle’s mission is to seize art back from the sort of critics who treat each painting “as a position paper, with the artist cast as a kind of philosopher manqué.” (Read more from the New York Times.)

Toxic Art: Is Anyone Sure What’s in a Tube of Paint?

Artists get called many things—geniuses, madmen, rebels, unemployed—but rarely chemists. Painters, however, increasingly find that they need a degree in organic chemistry when they go to an art-supply store and try to buy a tube of paint. (Read more from the New York Observer.)

How to Work in the Art World without Selling Out Your Politics

What if you realized that an entire community of people were underrepresented in the arts, so you created your own area of study in college to push their work to the forefront? What if you spent the next thirty years trying to change the ratio? Would you have the perseverance to get there? (Read more from New York.)

Why Attend Conferences as a Freelance Academic?

Attending a conference without an institutional affiliation can feel alienating. That alienation, combined with the fact that many freelance academics are no longer searching for faculty positions, can make conferences seem like a colossal waste of time and money. What could you possibly contribute? (Read more from Vitae.)

Missing Out on the Fear of Missing Out

There are three openings tonight in three different parts of the city and it’s only possible to do one. Your old friend, your new friend, and the hip space that just opened. Now make a choice. Was it the right one? (Read more from Momus.)

New in caa.reviews

posted by CAA — October 21, 2016

Melanee C. Harvey reviews The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Purgatory and Hell Revisited by Contemporary Artists, an exhibition catalogue edited by Mara Ambrožič and Simon Njami. The volume expands on three exhibitions—each dedicated to a realm of the afterlife—and illuminates “the potential aesthetic and conceptual configurations in contemporary art that undermine parochial notions of African art.” Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Danielle Carrabino reads Faith, Gender and the Senses in Italian Renaissance and Baroque Art: Interpreting the Noli me tangere and Doubting Thomas by Erin E. Benay and Lisa M. Rafanelli. Comparing the two religious narratives, the authors combine “feminist theory and notions of reception” to argue that gender dictates the way Mary Magdalene and Thomas “experience the resurrected body.” Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Allison Myers discusses International Pop, a traveling exhibition organized by the Walker Art Center. The “ambitious show” aims to “overturn the idea of Pop as a primarily American and British movement by redefining it as a fluid sensibility with international reach.” At the Dallas Museum of Art, the layout “underscores the exhibition’s stakes in the conversation on global art history.” Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Caa.reviews publishes over 150 reviews each year. Founded in 1998, the site publishes timely scholarly and critical reviews of studies and projects in all areas and periods of art history, visual studies, and the fine arts, providing peer review for the disciplines served by the College Art Association. Publications and projects reviewed include books, articles, exhibitions, conferences, digital scholarship, and other works as appropriate. Read more reviews at caa.reviews.

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by Christopher Howard — October 19, 2016

Each week CAA News summarizes eight articles, published around the web, that CAA members may find interesting and useful in their professional and creative lives.

“All art is political”: A Conversation with Hank Willis Thomas

Cofounded in January by Hank Willis Thomas as the first artist-run super PAC, For Freedoms has been working tirelessly to engage the public in critical discourse about our political system. For those unfamiliar, a super PAC is an independent political action committee that can raise unlimited funds from corporations, unions, associations, and individuals. (Read more from Arts ATL.)

Make No Mistake, Art History Is a Hard Subject. What’s Soft Is the Decision to Scrap It

In the UK, art history A-level is to be scrapped in 2018. The decision taken by the exam board AQA seems related to the Conservative government’s policy of ranking subjects by perceived relative difficulty, using an analogy of “soft” and “hard” that may be designed to belittle students and teachers who have apparently taken the easy way out. (Read more from Apollo.)

Where Social-Media Sensation Kimberly Drew Sees the Art World in Ten Years

Kimberly Drew stands as one of black contemporary art’s most visible champions. With north of 100,000 followers subscribed to her Instagram handle alone—joined by thousands more across Twitter and Facebook—Drew’s presence is fortified by the type of institutional sheen that comes with running the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s social-media channels. (Read more from Artnet News.)

How Many Hours a Week Should Academics Work?

How many hours do you work in a week? Many academics feel overworked and exhausted by their jobs. But there is little evidence that long hours lead to better results, while some research suggests that they may even be counterproductive. (Read more from Times Higher Education.)

Tasked with Creating a Catalogue Raisonné, These Art Historians Become Detectives

“Something like provenance is the most time-consuming aspect of a catalogue raisonné because, basically, it is detective work,” said Katy Rogers, who coauthored the Robert Motherwell catalogue raisonné and currently serves as the project’s director. “You’re tracking down people, and you’re finding out their stories.” (Read more from Artsy.)

Data Ethics Is a Challenge That Major Foundations Can’t Afford to Ignore

If I ask you to picture “big data,” what do you think of? You probably didn’t think first of a grant-making foundation, social-justice group, or humanitarian-assistance organization. Compared to government agencies and large companies, key players in the social sector lag far behind in realizing the potential of data-intensive methods. (Read more from Equals Change Blog.)

Should We Kill the Conference Panel?

The reality is that the room dynamics of panels just don’t work all that well. It is difficult for panelists to build a narrative that will capture the audience’s attention. Panel discussions become performative rather than enlightening or challenging, and none of us is as good at speaking extemporaneously as we think we are. (Read more from Inside Higher Ed.)

The Middle Market Squeeze, Part II: A Reality Check for Art Galleries

If a flush but lopsided art economy invites confusion, it also demands takeaways. The against-all-economic-odds gallery once begun with boundless ambition and maxed-out credit cards is no more. Here’s the same idea put differently: the era of undercapitalized, illiquid, labor-of-love galleries that rely mostly or exclusively on the primary market for sales is over. (Read more from Artnet News.)

South African Diary

posted by Janet Landay, Project Director, CAA-Getty International Program — October 18, 2016

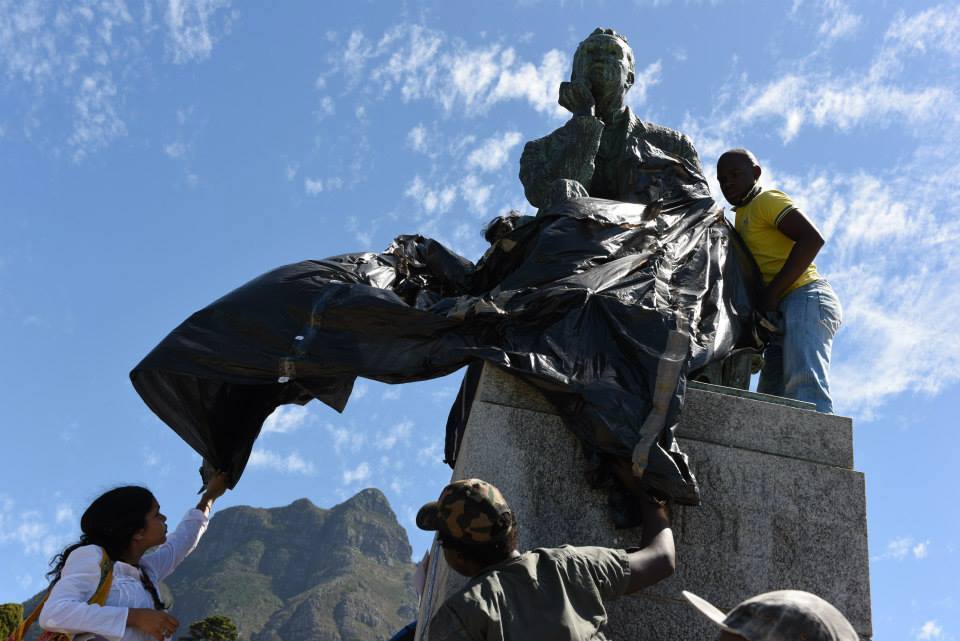

Rhodes Must Fall, downloaded from https://www.facebook.com/RhodesMustFall/photos

Posted by Janet Landay, Project Director, CAA-Getty International Program (for CAA News and the International Desk)

This summer I was invited by two alumni of the CAA-Getty International Program—Karen von Veh and Federico Freschi, both from the University of Johannesburg—to attend the 31st Annual Conference of the South African Visual Arts Historians (SAVAH). In the first five years of the CAA-Getty program, seven art historians from South Africa have participated—the most from any single country. Their strong presence at CAA’s Annual Conferences suggests a robust community of scholars, and I was eager to witness it firsthand.

In late July I flew to Johannesburg, where I met up with Rosemary O’Neill, associate professor of art history at Parsons the New School of Design and chair of CAA’s International Committee, who was also participating in the conference. On the day we arrived there was an intense thunderstorm followed by large hail. Our hosts, Karen von Veh and her husband Bengt, assured us that this was not normal for a Johannesburg winter. By the next day the sun had come out, and it remained sunny and pleasantly cool for the rest of our stay.

The weather may well serve as a metaphor for the abnormal state of affairs in South Africa: unusually stormy one day, seemingly calm the next. Twenty-two years after the end of apartheid, the country, and especially its university system, is in an enormous state of flux. Since March 2015, students have militated against South Africa’s twenty-three government-funded universities in two related protests. The first was Rhodes Must Fall, which demanded the removal of a sculpture of Cecil Rhodes, the embodiment of British racist colonial imperialism, from the University of Cape Town (UCT), and included the broader demand for decolonizing the university system, including curricula, language of instruction, and workers’ rights.

In October 2015 came Fees Must Fall, prompted by the announcement of a steep increase in fees at the University of Witwatersrand. Both movements have had successes: the UCT sculpture of Rhodes was removed, and many other public symbols of colonial rule have been taken down or defaced; students at Rhodes University persuaded authorities to consider renaming the school; and the government announced there would be no tuition increase for 2016. (This issue is being debated again, as increases for 2017 have elicited renewed protests.) These events are taking place at the same time that the government is reducing financial support for the universities.

Art, Design and Architecture Building at the University of Johannesburg, downloaded from university website, https://www.uj.ac.za/faculties/fada/Pages/Facilities.aspx

This was the context for SAVAH’s Annual Conference, as approximately sixty professors of art history, visual culture, and studio art gathered at the University of Johannesburg for three days of papers and discussion. Organized by Federico Freschi (executive dean), Brenda Schmahmann (research professor), and Karen von Veh (associate professor), all from the Faculty of Art, Design, and Architecture at the University of Johannesburg, the conference was titled “Rethinking Art History and Visual Culture in a Contemporary Context.” The ongoing crisis in higher education charged the sessions and discussions with particular intensity. The subjects addressed, whether historical, pedagogical, or political, were not chosen solely for theoretical considerations; speakers were seeking practical solutions to the immediate challenges they face as scholars and teachers in post-apartheid South Africa.

An underlying theme of the conference—how can art history be relevant and useful to scholars and students at this charged moment in time?—was a subtext in Steven Nelson’s eloquent keynote address. In a discussion of works by Houston Conwill, Moshekwa Langa, and Julie Mehretu, Nelson—a professor of African and African American art and director of the Center for African Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles—considered how the use of mapping and geography by these artists has reshaped our understanding of African ancestry, notions of diaspora, and urban spaces. The weaving of past and present, continental Africa and the African diaspora, and art-historical analyses of traditional forms and new media exemplified the ongoing relevance of the art-historical discipline to understanding contemporary art and culture.

Session topics during the two-day conference ranged from “International Curatorial Practices” to “The Politics of Display in South Africa” and “Decolonizing Education (Parts I and II)” to “Postcolonialism beyond South Africa.” Alison Kearney, a lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand, delivered a paper titled “Art history is dead—long live art history!” in which she explored the deeper meaning of decolonizing the university, beyond the tokenistic call for more black authors and artists. This decolonization will lead to “the inevitable end of art history” and a return to the work of art and an interdisciplinary approach as a “deliberate means of destabilizing a single disciplinary gaze.” Fiona Siegenthaler, a senior lecturer at the Institute for Social Anthropology, Universität Basel, compared the call for decolonization in South Africa to the one in Uganda. Because the population in Uganda is overwhelmingly black, the call for decolonization has little to do with the racial profile of its teachers or students. Rather, the country is focused on rewriting curricula to be more relevant to their students’ lives. Both countries, she stated, are skeptical about the hegemony of neoliberalism as a form of neocolonialism, on the one hand, and the need for access to international contemporary art, art institutions, art markets and funding organizations, on the other.

Several speakers explored alternative approaches to current studies in South African art history. Lize van Robbroeck, from the University of Stellenbosch, spoke about “settler colonial studies” and a multinational research project she is part of that examines settler life in five former British dominions: New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, Australia, and the United States. The cultural, economic, and political circumstances in each of these colonies, in spite of particular dynamics in each, created comparable artistic products in the early to mid-twentieth century. The group’s research suggests that the demands to establish national art canons in each of these locations led to a corresponding art-historical neglect of the striking cross-national similarities in the art produced by artists in each place.

A paper by Jackson Davidow, from the Department of Architecture at MIT, called on the discipline of art history to enlarge its approach to “traverse geographies, temporalities, environments, and communities.” He made the case by discussing a global history of AIDS activist art, which must still be historically contextualized within local landscapes. His paper posed a crucial question to contemporary scholars: “How can global art histories work to decolonize and deconstruct the practices of our discipline rather than perpetuate its oppressive structuring?”

The conference ended with two papers from other humanities disciplines. The first one, by Brett Pyper from the University of the Witwatersrand, was about curating indigenous musical performances at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown. Leana van der Merwe, of the University of Pretoria, delivered the second, which was about an “African” feminist philosophy of art. Many of the conference papers will be published in an upcoming issue of De Arte, a peer-reviewed South African journal on visual arts, art history, and art criticism.

The SAVAH conference was not the only significant art event taking place in Johannesburg during my visit. The meetings coincided with a historic exhibition held downtown at the Standard Bank Gallery: the first-ever presentation on the African continent of paintings and works on paper by Henri Matisse.

Henri Matisse, The Horse, the Rider and the Clown,1947, fifth plate of the book Jazz, Musée Matisse in Le Cateau-Cambrésis

Juxtaposed against the topic of the conference—rethinking art history in a contemporary context—this major exhibition provided another bellwether of the state of art history in South Africa. The absence of Matisse exhibitions in the entire continent until now can partially be explained by practical reasons related to insufficient resources (shipping and insurance costs, museum-quality exhibition spaces, etc.), but it is also likely due, in part, to a reluctance or lack of interest on the part of European and American collections and African-based organizers to bring the artist’s work to African audiences, in spite of Matisse’s great interest in African art. During my visit to South Africa, I was struck by the lack of Western art displayed in the museums, with the exception of a small collection on view at the National Museum in Cape Town. Little access to this art is yet another challenge for professors of art history, and it must relate to the absence of Matisse exhibitions as well. Why should South Africans be interested in his work if, for many, he is an unknown, dead white European artist? There is an audience for Matisse in South Africa, including the well-educated professional class and an active, sophisticated group of collectors who support a growing number of commercial galleries. There is also a vibrant community of artists in South Africa whose work characteristically draws on indigenous artistic traditions as well as global art. In spite of the limited audience—or perhaps because of it—a Matisse exhibition in Johannesburg is an important event, a major step toward broadening an appreciation of global art and its history.

In Johannesburg, the Matisse exhibition was the fourth in a series of presentations at the Standard Bank Gallery of works by twentieth-century modern European masters. Previous projects focused on Mark Chagall, Joan Miró, and Pablo Picasso. Through the curatorial efforts of Federico Freschi and Patrice Deparpe, director of the Musée Matisse in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, the exhibition Henri Matisse: Rhythm and Meaning was on view at the Standard Bank Gallery from July 13 to September 17, 2016. It included significant paintings, drawings, collages, and prints covering all the dominant themes in the artist’s oeuvre, from his early Fauvist years to the paper cut-outs produced in the last years of his life. As Freschi noted in introductory remarks, “Of particular interest to South African audiences is the inspiration Matisse took from African and other non-Western art forms during the early 1900s while struggling to find a new visual language to express the particular experience of the new, modern age.”

Patrice Deparpe, Director of the Musée Matisse in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, in the exhibition Henri Matisse: Rhythm and Meaning, downloaded from website of the Embassy of France in South Africa.

To open the SAVAH conference, a lecture, gallery talk and reception for the exhibition was held the evening before the conference proceedings began. Rosemary O’Neill presented a thought-provoking lecture titled, “Henri Matisse: Fluid Memory, Embodied Signs.” Her paper considered aspects of Matisse’s work in relation to the construct of memory, time, and intuitive expression, as well as the influence of the ideas of philosopher Henri Bergson. In discussing Jazz, O’Neill identified ways in which his Tahitian memories from 1930, as well as his own cultural context and artistic trajectory, resulted in the realization of the innovative process and expression soon evident in Matisse’s late cut-outs; their importance in relation to a revival of the decorative impulse in postwar France; and their analogous relationship to poetic and musical phrasing—that is, a system of ensemble signs—as articulated in the writings of the poet Louis Aragon. Freschi’s subsequent gallery talk elaborated on Matisse’s exploration of African modes of representation in his early works; then, calling special attention to the series of prints that comprise the artist’s book, Jazz, he emphasized the influence of his travel to Tahiti and the archipelago islands that appear in his use of patterns and rhythms, ephemeral materials, and a conceptual rather than perceptual approach to image making.

For an American visitor, the conference and exhibition provided much food for thought. It was impossible to ignore similarities in the dissatisfactions of university students in both countries. Like their South African counterparts, U.S. students are demanding a greater diversity of voices in the curriculum, on the faculty, and in the administrations of colleges and universities. In both countries, growing complaints about racial inequality and ties to apartheid or slavery have resulted in important, if mostly symbolic, changes. At about the same time that South African authorities were removing sculptures of Cecil Rhodes and suspending tuition hikes, leaders at Georgetown University announced efforts to make amends for its complicity in the nation’s slave trade, including preferential admissions for descendents of slaves sold in 1838 by Maryland Jesuits to stave off the college’s bankruptcy. Other schools, such as Brown University, Harvard University, Emory University, and the University of Virginia, have made their historical ties to slavery public and announced plans such as renaming buildings, creating racial justice programs, and erecting memorials acknowledging their ties to the transatlantic slave trade.

[Just last week in New York City, as part of an anti-Columbus Day protest, a diverse group of protesters, united under the banner “Decolonize This Place,” demanded the removal of an equestrian sculpture of Theodore Roosevelt (flanked on either side by a Native American and an African American) at the entrance to the American Museum of Natural History. The crowd included activists from the Black Lives Matter, Indigenous rights, and other labor and social justice movements. Calling it “the most visible symbol of white supremacy in New York,” the group also called for “decolonizing of the museum,” citing specific exhibits within the museum that highlight its history of white supremacy and colonialism. The demonstration was one of many across the country protesting the continued observance of Columbus Day, demanding that it be replaced by Indigenous People Day.]

From my vantage point as a participant at the SAVAH conference, the most striking similarity between the two countries was the paucity of people of color among art history professors and students. This was the great unspoken problem at the conference, evidenced by the prevalence of white faculty and students at a gathering focused on decolonization, art and activism, and keeping art history relevant. There were a small number of people of color at the conference among both speakers and attendees, but much like at a CAA Annual Conference, the dominant color was white. The answer is not, as some radical South African students demand, to rid the curriculum of all European content, or to replace all white professors with black ones; rather, it lies both in a multiplicity of voices and a questioning of assumptions rooted in the foundational texts of the field. Solving this problem may be the greatest challenge to art history’s relevance, even as progress is made alongside the slow path to racial equality.

South Africa is sometimes called a Petri dish for studying race relations. Only twenty-two years away from government-enforced racism, the country’s efforts in building a democratic, racially equal society offer many lessons about effective and less effective ways to accomplish radical change. The art historians I met in Johannesburg have created a vital community in which to study and struggle with these lessons. They are keeping the discipline of art history alive and relevant to the cultural and political challenges they face. But how they do it may provide important guidelines for scholars in the United States. In spite of numerous differences between the two countries—especially in scale, resources, and history—both South African and U.S. art historians are grounded in the same antecedents. How to retain the strengths of a discipline born in nineteenth-century Germany while stretching its geographic parameters to include all cultures is a challenge we all face.

Comment on this article in the Diversity in the Arts community on CAA Connect.

A CAA Road Trip

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — October 18, 2016

Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine (photograph by Janet Landay)

Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine (photograph by Janet Landay)In late September, Hunter O’Hanian and I had the pleasure of spending a weekend at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, to attend two CAA events hosted by Anne Goodyear, codirector of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and a former CAA president. We arrived at the picturesque New England campus on a beautiful fall day. The college’s art museum, one of the oldest in the country, anchors the western edge of the quad, its neoclassical façade presiding gracefully over green lawns and majestic trees where students played Frisbee, read, or walked across campus. It was a perfect weekend to welcome CAA members to campus.

The first group arrived that Saturday afternoon to attend a CAA member reception, the first of several Hunter has planned around the country to provide an opportunity for him to meet with members in a relaxed setting and talk about CAA. The event began with a tour of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art given by Anne and her husband, the museum’s codirector, Frank Goodyear. Immediately following, we all walked a block away to Anne and Frank’s house to enjoy some wine and cheese on their back patio. The fifteen or so participants hailed from several schools and museums in addition to Bowdoin—Colby College, Bates College, the Portland Museum of Art, and the Farnsworth Art Museum—and included art historians, artists, librarians, and independent scholars.

Members spoke in turn about their most memorable CAA experiences: attending a first conference, interviewing and getting a job, meeting old friends, or networking with scholars in their fields. Hunter then shared thoughts about his goals for CAA based on what he has learned from members since he became executive director in July. He observed the importance of connectivity—how to keep CAA members in touch with issues in the field, but especially how to keep them in touch with each other. And he described many of the changes members will experience at the next Annual Conference, including a focus on personal experience, captured by a new theme for the meetings, myCAA.

On Sunday morning, several of the same CAA members returned, joined by others from around the state, for a half-day workshop about copyright and fair use. Peter Jaszi, a co–lead investigator on CAA’s Fair Use Initiative, came from Washington, DC, to Bowdoin to lead the program, which focused on how visual-arts professionals can use CAA’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts in their work. Following an introduction to copyright and fair use, the workshop began with a look at how museum professionals can use the Code when employing copyrighted materials in their work.

Participants had been asked to bring real-life questions with them. Thus, a museum director wanted to know whether his museum could allow photography in the galleries of works still protected by copyright. A curator described a challenge she had in getting an image for a catalogue from a museum in central China. When she received no reply from the museum, she resorted to scanning the image from another book. Is that fair use? Other questions involved loan forms, credit lines, and online projects.

As the day continued, the program moved on to address questions from professionals in other areas: librarians and archivists, professors and teachers, artists and independent scholars. Can a faculty member use images in class that she got from a flash drive she had received from a foreign museum? What kind of credit information is necessary for a blog about films? Is Shepard Fairey’s image of Obama a good case study for students learning about fair use? How should the institutional repository on a college campus view the copyright protection of yearbook photographs? By the end of the afternoon, a remarkable range of questions had been discussed, and the forty participants came away with a much greater understanding of fair use and how to rely on it in their work.

Peter Jaszi and Kyle Courtney at CAA’s fair-use town hall at Harvard University (photograph by Janet Landay)

Peter Jaszi and Kyle Courtney at CAA’s fair-use town hall at Harvard University (photograph by Janet Landay)On Monday, Hunter, Peter, and I were in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to join Kyle Courtney, a copyright specialist in Harvard’s Office for Scholarly Communication, for a fair-use town hall on the campus of Harvard University. As in Maine, Peter began the program with an introduction to fair use, and I followed with a description of CAA’s Fair Use Initiative. Kyle spoke about a program he directs at Harvard that trains librarians to be “first responders” to users’ questions about fair use. Although relatively new, the program has proven to be an effective way to support and teach visual-arts professionals about fair use. It is now being replicated on other university campuses. The event was then opened to questions from the sixty-five members of the audience, which Peter and Kyle discussed in depth.

Many of the topics were similar to those that had been addressed at the Bowdoin workshop, but a new subject emerged as well: advocacy. Does a professor who has had a manuscript accepted have any recourse when her publisher requires signed author agreements stating that all images had been cleared for publication and all fees paid? The answer is yes; she can ask her publisher to read CAA’s Code and explain that many, if not all, of her uses of images comply with the doctrine of fair use. While the effort may not succeed (though CAA has several success stories on file), over time it will familiarize publishers with the principles outlined in the Code. Changes have already taken place, in large part due to this kind of challenge from users. Yale University Press now accepts fair-use defenses from its authors who are publishing monographs; the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation embraced a fair use policy for that artist’s work; and CAA not only encourages its authors to consider whether or not their uses are fair, but it also indemnifies authors against lawsuits about works used under fair use.

The program concluded with a reminder that CAA is happy to answer questions about fair use; please don’t hesitate to contact us at nyoffice@collegeart.org.

The CAA member reception at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (photograph by Janet Landay)

The CAA member reception at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (photograph by Janet Landay)Later on Monday, Hunter and I joined another group of CAA members at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design for a wine-and-cheese reception at the school’s President’s Gallery and Bakalar and Paine Galleries. Attendees included a wide range of members, from professors who have belonged to the association for thirty years to new members just graduating from MFA programs. Lisa Tung, the gallery’s director and curator, kicked off the event with a tour of two exhibitions currently on view, Encircling the World: Contemporary Art, Science, and the Sublime and Women’s Rights Are Human Rights: International Posters on Gender-Based Inequality, Violence, and Discrimination. Hunter, who is a former vice president for development at MassArt, then invited participants to speak about how CAA is valuable to them. He emphasized the importance of hearing from members so that CAA can support them as fully as possible in this rapidly changing world.

CAA’s road trip continued in early October with another member’s reception in Portland, Oregon. Later this month we will convene a fair-use workshop in Seattle, Washington. More events are planned for early next year in Georgia and Virginia. Stay tuned!

The Bowdoin College fair-use event was organized by the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and CAA, with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The Harvard University fair-use event was organized by Harvard’s Office for Scholarly Communication, thanks to the generous support of the Arcadia Fund, and by CAA, with funds provided by the Mellon Foundation.

Committee on Women in the Arts Picks for October 2016

posted by CAA — October 16, 2016

Each month, CAA’s Committee on Women in the Arts selects the best in feminist art and scholarship. The following exhibitions and events should not be missed. Check the archive of CWA Picks at the bottom of the page, as several museum and gallery shows listed in previous months may still be on view or touring.

October 2016

Marking the Infinite: Contemporary Women Artists from Aboriginal Australia

Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane

Woldenberg Art Center, No. 202, 6823 St. Charles Avenue, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118

August 20–December 30, 2016

The Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane presents Marking the Infinite: Contemporary Women Artists from Aboriginal Australia, which offers a unique opportunity to appreciate the diverse practices of Aboriginal Australian women artists today. The exhibition features works by Nonggirrnga Marawili, Wintjiya Napaltjarri, Yukultji Napangati, Angelina Pwerle, Carlene West, Regina Pilawuk Wilson, Lena Yarinkura, and Gulumbu Yunupingu. Coming from remote areas of the island, these respected matriarchs and leaders use art to empower their respective communities.

Immersed in ancient cultural traditions, the presented artworks speak with individual voices to universal contemporary themes. Their subject matter range from remote celestial bodies and native flowers to venerable crafts traditions and women’s ceremonies. Each work is unique in facing fundamental questions of existence, asserting both our shared humanity and differences in experiencing and valuing the same planet. As a whole, this exhibition of contemporary women artists from Aboriginal Australia emerges as an evidence of the relevance of indigenous knowledge in the twenty-first century.

Contemporary Aboriginal Australian women’s painting emerged later than the men’s practice, attracting global attentio—especially since the 1990s. Since women began to paint later, they were exposed to a broader range of global cultures. As Hetti Perkins mentions in her catalogue essay for Marking the Infinite, “While cultural activity has always been central to the secular and sacred lives of women, art making in recent decades has offered a key means for women to also maintain their social and economic independence.”

Eleni Panouklia: Its Luminous Saying Must be Left a Conjecture

Palaio Elaiourgeio

Eleusis, Greece

September 4–November 15, 2016

Palaio Elaiourgeio presents Its Luminous Saying Must be Left a Conjecture, a large-scale installation by Eleni Panouklia. Throughout this site- and time-specific mixed-media intervention that is meant to be experienced at night, Panouklia (born in Agrinio, 1972) converts industrial ruins of Palaio Elaiourgeio (Old Oil Mill) of Eleusis into an evocative earthy soundscape of dark paths and inaccessible sanctuaries.

The installation begins and ends in the backyard of the derelict factory, and it consists of two cyclically communicating outdoor and indoor environments allowing individual and collective explorations. The work immerses the viewer in a contrapuntally structured experience of darkness by transforming the backyard of Palaio Elaiourgeio into a disorderly, pulsating landscape of powerful sonorous enclosure and combining that with a lonely ritual itinerary through the silent passageway of a long building, where an interactive event awaits each viewer. Together, the two environments seek to affectively advance both timely critical and timeless existential realizations through distinct bodily and reflective enlightenments, or, better yet, “un-concealments” of the wholeness of being in darkness.

Curated by Kalliopi Minoudaki, Its Luminous Saying Must be Left a Conjecture orchestrates the awakening of multisensory explorations through the creative collaborations with the sound designer Coti K., the light designer Katerina Maragoudaki, the photographer Vassilis Xenias, and the production organizer and design consultant Georgia Voudouri.

Candice Lin: A Body Reduced to Brilliant Colour

Gasworks

155 Vauxhall Street, London SE11 5RH, UK

September 22–December 11, 2016

Gasworks presents A Body Reduced to Brilliant Colour, the first UK solo exhibition by the American artist Candice Lin. Born in Massachusetts in 1979, Lin makes work that engages with notions of gender, race, and sexuality by examining discrepant bodies, vibrant material, and disobedience. In A Body Reduced to Brilliant Colour, the artist explores how histories of slavery and colonialism have been shaped by human attraction to particular colors, tastes, textures, and drugs. Drawing from scientific theories, anthropology, and queer theory, Lin traces the materialist urges at the root of colonial violence.

The exhibition includes a low-tech installation of tubing, plastic and glass containers, porcelain filters, hot plates, and other hacked household objects; her work boils, ferments, distils, dyes, and pumps liquid containing colonial trade goods such as cochineal, sugar, and tea. Transforming prized, historically loaded commodities into a stain reminiscent of murder, feces, or menstrual blood, the exhibition speaks to these fraught histories of conquest, slavery, torture, and theft, while exploring what happens when materials so loaded with history and meaning are situated in new systems of relations.

The exhibition is accompanied by a series of events, including Eating the Edifice, an illustrated lecture/demonstration by the food historian and artist Ivan Day that will outline the evolution of edible table art from the early Renaissance to the nineteenth century.

Complaints Department: Workshop operated by the Guerrilla Girls

Tate Exchange / Switch House

Level 5, Tate Modern, Bankside, London SE1 9TG, UK

October 4–9, 2016

From October 4 to 9, the Guerrilla Girls will operate a Complaints Department. Individuals and organizations are invited to Tate Exchange to conspire with the girls and to post complaints about art, culture, politics, the environment, or any other issue they care about. Throughout the week, a series of workshops and thematic discussions will be presented, encouraging participation and assisting the public in creating statements to post on rolling bulletin boards. The week culminates in a special public event documenting and exploring what has been collectively complained about.

Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s

Photographers’ Gallery

16-18 Ramillies Street, London, UK

October 7, 2016–January 8, 2017

Featuring forty-eight international female artists, the Photographers’ Gallery opens its new exhibition, Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s, wholly curated from the Verbund Collection in Vienna. “The exhibition highlights groundbreaking practices that shaped the feminist art movement and provides a timely reminder of the wide impact of a generation of artists.” Works in photography, collage, performance, film, and video by well-known feminist trailblazers such as Cindy Sherman and Martha Rosler will be on view, along with overlooked artists such as Katalin Ladik and Birgit Jürgenssen. In fact, the exhibition includes many artists from areas of the world lesser known for feminist art.

“Through radical, poetic, ironic and often provocative investigations,” these artists used their work to question identities, gender roles, and the sexual politics of the 1970s. The exhibition is curated by Gabriele Schor from the Verbund Collection and Anna Dannemann of the Photographers’ Gallery.

The Listen Conference 2016: Feminist Futures

Bella Union

Level 1, Trades Hall, 54 Victoria Street, Melbourne, Australia

October 14–16, 2016

The three-day feminist music conference Listen returns this October with presentations, panel discussions, workshops, and live performances. “The Listen Conference provides a unique opportunity to engage in constructive discussion on ideas relating to gender, feminism, creativity, intersections within communities, writing, and performance.” Keynote speakers include the writer and feminist activist Clementine Ford and the New York–based performer and activist Alok Vaid-Menon (from the trans South Asian performance art duo Darkmatter).

Focusing on raising awareness and equality in the Australian music industry, “Listen” will cultivate “conversations from a feminist perspective around the experiences of marginalised people in Australia music.” Panels will encourage conversations on issues ranging from music making, the pros and cons of “call out culture,” race and sexism in music, and gender binaries in music and art, among other topics. The conference also features three nights of live music and movement-based performances, including experimental punk, Aboriginal mixes, dark techno, and poetry.

Adriana Marmorek: Love Relics

Nohra Haime Gallery

730 Fifth Avenue, 7th Floor, New York

September 14–October 15, 2016

Love Relics at Nohra Haime Gallery features photographs and videos by the Colombian artist Adriana Marmorek that document the ceremonial burning of twelve treasured objects associated with love. Most notable is the burning of Relic #16 and Relic #17, both wedding gowns, “showcasing the destruction of these institutional flags.”

The project originated at the end of another exhibition Reliquia, for which Marmorek exhibited fifty-one donated relics or treasures that represented memories of love or loved ones. When the exhibition finished, the artist chose to burn several of the relics, “digging deeper into the concept of eternity and ephemerality.” A ceremony was conducted for the owners of the objects, as she burned each and filmed them. “Some treasures—of love, happiness, sorrow and anger—had associated memories so deep that they had replaced the physical and enveloped an intense spiritual being.”

In addition to the videos, photographs are also on view, “capturing a split second in time,” while mementos such as an appointment book, a box of condoms, a matchbook, and a bridal bouquet are engulfed in flames.

Solo Exhibitions by Artist Members

posted by CAA — October 15, 2016

See when and where CAA members are exhibiting their art, and view images of their work.

Solo Exhibitions by Artist Members is published every two months: in February, April, June, August, October, and December. To learn more about submitting a listing, please follow the instructions on the main Member News page.

October 2016

Abroad

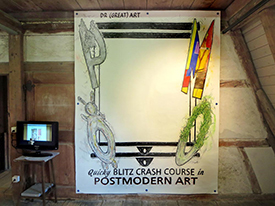

Mark Staff Brandl. Remise Kunsthalle, Weinfelden, Switzerland, August 20–September 10, 2016. Before Tomorrow: Eine Inszenierung der Postmodernen Kunst. Book project, performance-lecture, and painting-installation.

Virginia Maksymowicz. SACI Gallery, Studio Arts College International, Florence, Italy, September 5–October 16, 2016. Architectural Overlays/Sovrimpressioni Architettoniche. Photography, drawing, printmaking, and sculpture.

Blaise Tobia. ARCI Arcobaleno, Rome, Italy, September 12–October 8, 2016. La Scomparsa: The Disappearance of Italy.

Midwest

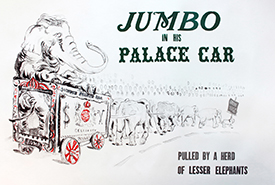

Ruthann Godollei. Soo Visual Arts Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, September 10–October 22, 2016. Herd Mentality: New Work by Ruthann Godollei. Printmaking and installation.

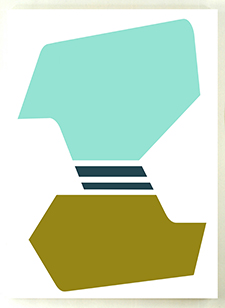

Jason Hoelscher. Hoffman LaChance Contemporary, Saint Louis, Missouri, September 2–24, 2016. Iconographic Overdrive. Painting.

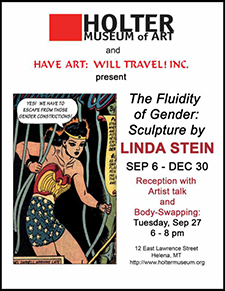

Linda Stein. Holter Museum of Art, Helena, Montana, September 6–December 30, 2016. The Fluidity of Gender: Sculpture by Linda Stein. Sculpture.

Linda Stein. Alverno College, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, August 23–October 1, 2016. Holocaust Heroes: Fierce Females; Tapestries and Sculpture by Linda Stein. Tapestry and sculpture.

Northeast

Theresa Antonellis. 42 Maple Contemporary Art Center, Bethlehem, New Hampshire, October 7–30, 2016. One Breath One Line. Breath-generated drawing.

Colleen Fitzgerald. Foster Gallery, Dedham, Massachusetts, September 12–October 14, 2016. and over again. Photography.

Angela Fraleigh. Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York, September 24–December 31, 2016. Angela Fraleigh: Between Tongue and Earth. Painting and sculpture.

Sharon Louden. Morgan Lehman Gallery, New York, September 8–October 8, 2016. Windows. Painting.

Michael Rich. Old Spouter Gallery, Nantucket, Massachusetts, July 29–August 10, 2016. All the Dawns of Summer. Painting.

South

Linda Stein. Museum of Biblical Art, Dallas, Texas, October 26–December 16, 2016. Holocaust Heroes: Fierce Females; Tapestries and Sculpture by Linda Stein. Tapestry and sculpture.

Installation view of Mark Staff Brandl’s exhibition Before Tomorrow (artwork © Mark Staff Brandl)

Installation view of Mark Staff Brandl’s exhibition Before Tomorrow (artwork © Mark Staff Brandl)

Ruthann Godollei, Jumbo’s Palace Car, 2016, lithograph, 32 x 43 in. (artwork © Ruthann Godollei)

Ruthann Godollei, Jumbo’s Palace Car, 2016, lithograph, 32 x 43 in. (artwork © Ruthann Godollei)

Jason Hoelscher, Sci-Fi Rothko, 2016, Benjamin Moore interior acrylic latex on canvas, 50 x 36 in. (artwork © Jason Hoelscher)

Jason Hoelscher, Sci-Fi Rothko, 2016, Benjamin Moore interior acrylic latex on canvas, 50 x 36 in. (artwork © Jason Hoelscher)

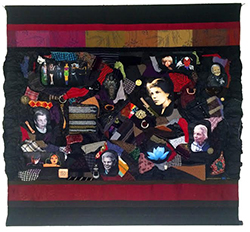

Linda Stein, Gertrud Luckner 843, 2015, leather, archival pigment on canvas, fabric, metal, and zippers, 54½ x 59 x 2 in. (artwork © Linda Stein)

Linda Stein, Gertrud Luckner 843, 2015, leather, archival pigment on canvas, fabric, metal, and zippers, 54½ x 59 x 2 in. (artwork © Linda Stein)

Theresa Antonellis, installation view of One Breath One Line at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, 12 ft. tall (artwork © Theresa Antonellis)

Theresa Antonellis, installation view of One Breath One Line at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, 12 ft. tall (artwork © Theresa Antonellis)

Colleen Fitzgerald, K, 2016, pigment print, 29½ x 23¼ in. (artwork © Colleen Fitzgerald)

Colleen Fitzgerald, K, 2016, pigment print, 29½ x 23¼ in. (artwork © Colleen Fitzgerald)

Angela Fraleigh, the breezes at dawn have secrets to tell, 2015, oil and silver metal leaf on linen, 90 x 66 in. (artwork © Angela Fraleigh)

Angela Fraleigh, the breezes at dawn have secrets to tell, 2015, oil and silver metal leaf on linen, 90 x 66 in. (artwork © Angela Fraleigh)

Sharon Louden, Windows, 2016, oil on paper, 8¼ x 11¾ in. (artwork © Sharon Louden)

Sharon Louden, Windows, 2016, oil on paper, 8¼ x 11¾ in. (artwork © Sharon Louden)

Michael Rich, Moksha, 2016, oil and wax on canvas, 28 x 26 in. (artwork © Michael Rich)

Michael Rich, Moksha, 2016, oil and wax on canvas, 28 x 26 in. (artwork © Michael Rich)

Linda Stein, Protector 841 with Wonder Woman Shadow, 2014, leather, metal, and mixed media, 78 x 24 x 8 in. (protector only) (artwork © Linda Stein)

Linda Stein, Protector 841 with Wonder Woman Shadow, 2014, leather, metal, and mixed media, 78 x 24 x 8 in. (protector only) (artwork © Linda Stein)