CAA News Today

An Interview with Suzanne Preston Blier on CAA’s Code of Best Practices and Publishing with Fair Use

posted by CAA — May 19, 2020

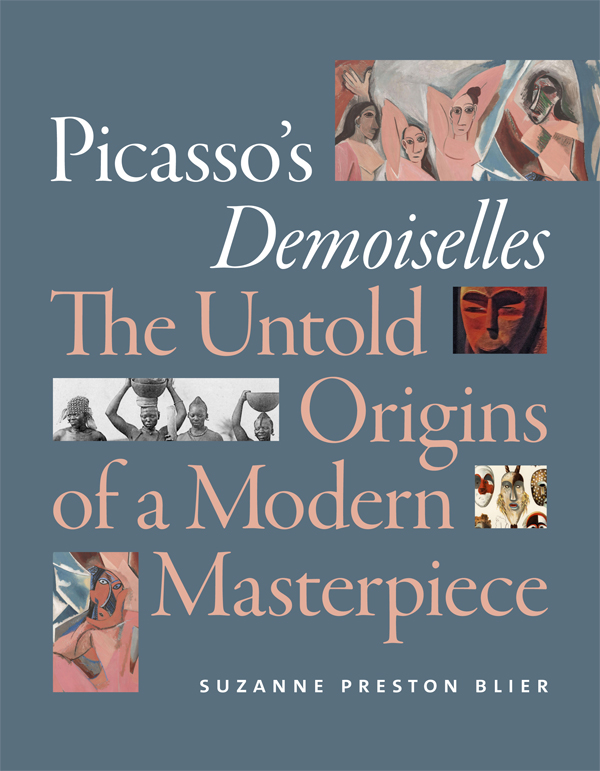

In 2019, Suzanne Preston Blier, professor of African art at Harvard University and former president of CAA, published a major book on Picasso’s use of global imagery, Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece. In addition to its scholarship the book is groundbreaking for its reliance on fair use, the principle within US copyright law that permits free reproduction of copyrighted images under certain conditions. CAA led the way among visual arts groups in calling for reliance on fair use, producing in 2015 its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

In 2019, Suzanne Preston Blier, professor of African art at Harvard University and former president of CAA, published a major book on Picasso’s use of global imagery, Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece. In addition to its scholarship the book is groundbreaking for its reliance on fair use, the principle within US copyright law that permits free reproduction of copyrighted images under certain conditions. CAA led the way among visual arts groups in calling for reliance on fair use, producing in 2015 its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

In this interview with Patricia Aufderheide, university professor and founding director of the Center for Media & Social Impact (CMSI) at American University, and a principal investigator in the CAA fair use project, Blier relates how she became an inadvertent pioneer of fair use in art history.

An Interview with Suzanne Preston Blier, Harvard University

By Patricia Aufderheide, American University

I met Prof. Blier, an award-winning art historian, when CMSI joined others in facilitating the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts for the College Art Association (CAA), with funding from the Samuel H. Kress and Andrew W. Mellon Foundations. Fair use is the well-established US right to use copyrighted material for free, if you are using that material for a different purpose (such as academic analysis, for instance) and in amounts relevant to the new purpose. Blier was the incoming president, as the Code launched.

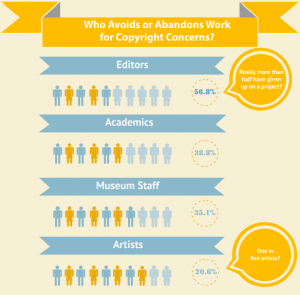

The project addressed a huge need. Art historians, visual artists, art journal and book editors, and museum staff all have faced major hurdles in accomplishing their work because of copyright. Art historians avoided contemporary art in favor of analyzing public domain material. Visual artists hesitated to undertake innovative projects that reuse existing cultural material. Editors, or sometimes their authors, faced monumental bills for permissions and sometimes those permissions depended on an artist or artist’s estate agreeing with what they say. Museums hesitated to do virtual tours, or use images in their informational brochures, or even to mount group exhibits, because of prohibitive permissions costs. All together, some people in the visual arts called this “permissions culture.”

Once the Code came out, some things changed immediately. Museums rewrote their copyright use policies. Artists made new work. CAA’s publications—some of the leading journals in the field—adopted fair use as a default choice.Yale University Press prepared new author guidelines for fair use of images in scholarly art monographs to encourage fair use. Blier was one of the Code’s champions.

And then she needed it herself. As she began work on her most recent book, which ultimately resulted in Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece (Duke University Press, 2019, winner of the 2020 Robert Motherwell Book prize for an outstanding publication in the history and criticism of modernism in the arts by the Dedalus Foundation), she realized the subject faced the stiffest possible copyright challenge. To tell her story, she would have to be able to show images from a variety of artists, most challengingly, Picasso. She thought of Duke University Press, a publisher that has been willing to go ahead of others on fair use. So Blier approached them. Duke was very supportive, and they ended up hiring extra legal counsel for this. In the end, Blier said, she had to rewrite certain sections, and redo some images at the suggestion of outside counsel, to strengthen the fair use argument.

Blier tells the story of how the book got out into the world (and won an award), below.

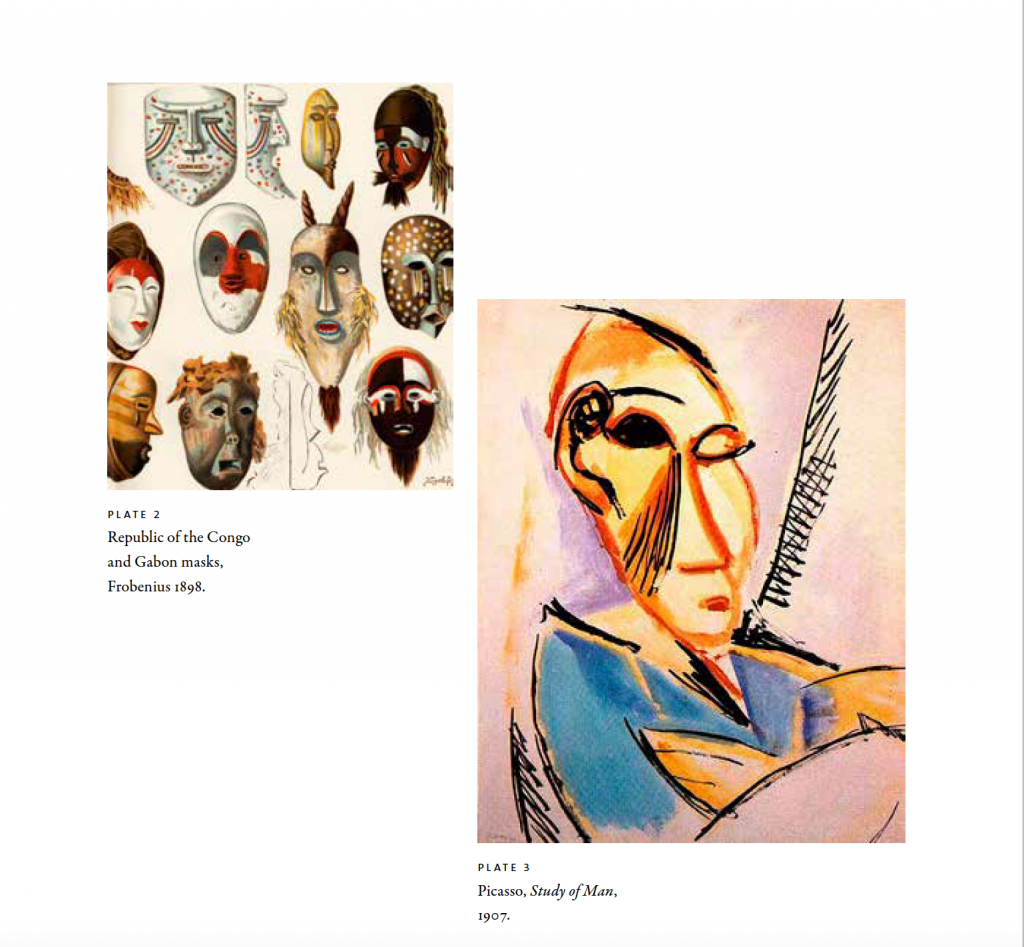

Figure 1. Congo masks published in Leo Frobenius’ 1898 Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas alongside Pablo Picasso’s Study of Man (1907). The Congo mask at the bottom, second from the left is the likely source for the crouching demoiselle. The mask at the top left shows tear lines from the eyes crossing diagonally down the cheeks similar to Picasso’s preliminary study for one of the men in an early compositional drawings for the canvas.

You’re an expert in African art. How did you end up writing a book about one of the most famous modernist artists?

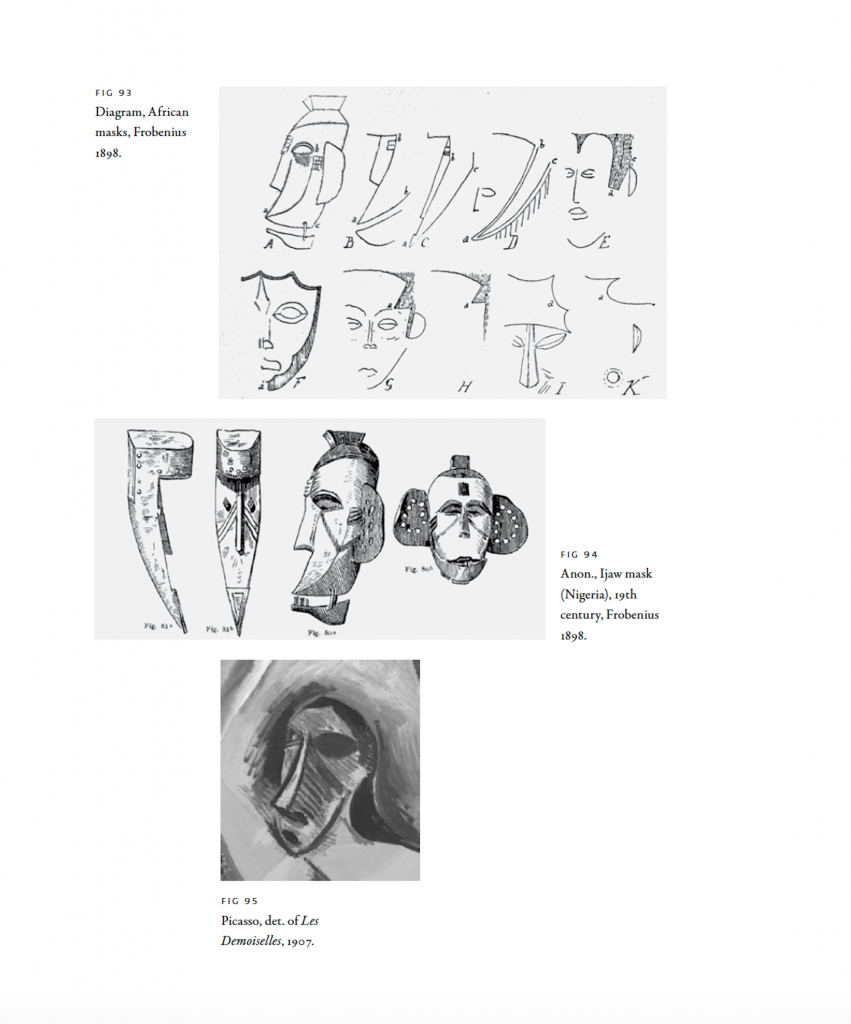

This is a book I never intended to write; it found me. For my previous book, Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba: Ife History, Power, and Identity, I was doing those last-minute bits of work in the library to check sources, and I pulled out a book adjacent to the book I was looking for, an old book by the German anthropologist, Leo Frobenius. I hadn’t read it since graduate school. As I opened it up, I looked down and I said, Wow, this is a book on African masks and they look like they’d be the ones Picasso used as models for his famous 1907 painting Demoiselles d’Avignon. At the time I had first read the book, Picasso’s drawings for the painting hadn’t been released. This time I saw it differently and as I was looking at it in the library, I saw there was tracing paper over the pictures. There was a line drawing covering each mask, and that seemed significant too.

The next thing I knew, I was hunting for a book from the Harvard library on Dahomey women warriors. It turned out it was in the medical school library, which should have been a sign. When I picked it up at the main library and flipped it open, I thought, Oh my god, it’s pornography! It was photos and line drawings of women around the world, in supposed “evolutionary” order. Photos of naked women begin with so-called “archaic,” in Papua New Guinea, right through to southern Europe, then Denmark. In the library I’m bending over, kind of hiding it, out of embarrassment. I bring it home and realize, Ohhhh! Here’s another key source for Demoiselles. This volume, which was by Karl Heinrich Stratz, had gone through multiple editions, and one was published about the same time Picasso stopped using living models. Then I found another book, by Richard Burton, which had a rendering that Picasso clearly used for his 1905 sketch Salomé.

What happened next was the clincher. I went to Paris to lecture at Collège de France. The week before my lectures, I went to hear another speaker at the Collège, a medieval historian. One of the first slides he presented was a work from a medieval illustrator, Villard De Honnecourt. This book was a modern edition of an illustrated medieval manuscript, published in the right time frame for Picasso to have seen it. And I thought, Well, here’s another source Picasso used.

Later I was also able to rediscover a photo that allowed me to date the painting to a single night in March 1907. The scene is often identified as a brothel, but bordel in French doesn’t mean bordello, but rather a chaotic or complex situation. It was my belief that Picasso was creating a time-machine kind of image of the mothers of five races, as he understood them from the Stratz ethno-pornography book and other sources, each depicted in the art style of that region or period. My larger argument is not only that Picasso was using book illustration sources, but also that these books invite us to see the canvas in a new light, and that, for Picasso, the painting has its intellectual grounding in colonial-era ideas about human and artistic evolution.

Figure 2. Illustrations from Leo Frobenius’ 1898 Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas showing (top two rows) the visual development of a mask into a human face. The middle illustration ,from the same Frobenius book shows line drawings of ijaw masks from Nigeria. The bottom image is a detail of the standing African figure from Picasso’s 1907, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon which appears to be based on a combination of these two masks.

What a sleuthing job! And so you decided to write the book then?

I wrote the first two chapters while I was in Paris doing the lecture. I saw it not as a coffee-table art book, but the kind of book you put in your knapsack as you head off to a long ride on the subway.

It was easy to write, but it was a very different story for the images. I immediately got a trade publisher in Britain to agree to publish it, and then they said they could not do it, because of problems getting permission to reproduce images from the Picasso Foundation.

The Picasso Foundation is notorious for making it difficult to access Picasso images, isn’t it?

The price of permissions is high, and this Foundation like many estates is interested in guarding the artist’s reputation as well. The difficulties of publishing on Picasso have been manifested in how little publishing was being done, and how scarce the images were in that work. Since 1973, there have been few heavily illustrated books about Picasso, except by wealthy individuals or museums in relation to an exhibition. I had heard about Rosalind Krauss publishing a work without permissions—at least that’s what I heard—anyway, she used very few images. Leo Steinberg apparently had not been able to arrange the rights for a work he wanted to do, a book edition of his two seminal articles on Les Demoiselles.

Although I hadn’t realized it until recently, in September 2019 there was an important case in the US, about a set of illustrated books by Christian Zervos with a wide array of Picasso illustrations. The case was started in France, but a US judge has allowed fair use.

But generally, yes, there’s common wisdom among art historians that the Picasso Foundation is a formidable challenge.

So how did you proceed when the first publisher backed out?

I was disheartened, but I got an agent. He sent it off to ten or twelve trade publishers worldwide—and came up with nothing.

Then I realized I was going to have to go to a university press. That was a big decision. The trade publication will pay for the images, and do all the work on the rights clearance. But with a university press, you’re on your own.

One of the first people I contacted was legendary editor Ken Wissoker at Duke University Press. He was interested, but then came the issue of the images. I may have broached fair use with him from the start. The manuscript had gone through peer review and it was in great shape except for this copyright issue. I had quite a number of images—in the end, it was 338. At Duke, they won’t begin the editorial process until you have all the copyright clearances on images done. So I began the difficult process of deciding how to get the images.

Were you in contact with the Picasso Foundation directly?

I did contact them, in order to let them know about the project in general. I was doing final research work in Paris. I had framed the book as a travelogue in part addressing my discovery of these sources. I also wanted to find out so much more about Picasso. I’m not a modernist, I’m an outsider to the field. So I worked hard to get as much insight and criticism of the manuscript from specialists as I could.

I made it a point to meet with people at the Picasso Foundation. I had a Powerpoint of the images, which I showed to one of the key people there. Later I wrote to them, “here’s the manuscript, let me know if you have any thoughts.” And I heard nothing back. I had heard that with some manuscripts, they have been concerned one way or another. I didn’t want their permission for the intellectual content, but since they knew this artist and his life and family better than any academic could, I wanted their insights.

And then you started to look for permissions?

Well, I began to think about the cost of acquiring the images. The process is such that you have to go through the Artists Rights Society (ARS, a US licensing broker). And to get a price, you have to furnish the number of images, how many are color, the size of the print run, the prospective profit, and a whole series of things we could not know. Duke wouldn’t even look at the project editorially without having the rights in hand. I had heard difficult stories—that they were interested in looking at the galleys along the way, and requesting changes, for quality control, but it wasn’t possible to do this and work with the press.

If I had to guess, I would say that it might have cost me something like $80,000 of my own money to purchase the minimum number of images for this scholarly book, from which I expect to make no money, or very little.

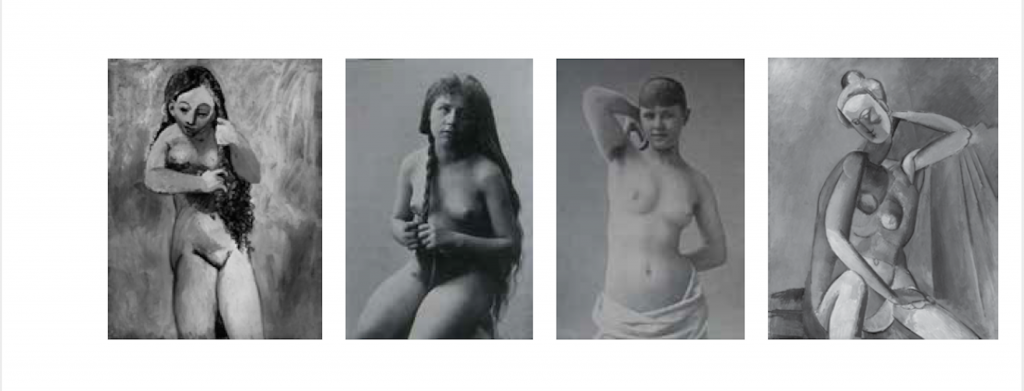

Figure 3 from left to right: Pablo Picasso, Nude Combing Her Hair, 1906; Girl braiding hair from C. H. Stratz, La beauté de la femme, 1900 (Paris); Girl from Vienna from C.H. Stratz, La beauté de la femme, 1900; Picasso Seated Female Nude, 1908. Over the course of his long career Picasso would continue to use key visual insights from Frobenius, Stratz, and other illustrated sources he was exploring in this late 1906 to early 1907 period.

So how did you come to the decision to use them under fair use?

I had been president of CAA in 2016-17, and a longtime promoter of fair use and IP issues more generally. I was involved in the creation of the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. For me, CAA’s role in fair use is one of the most important and radical (in a positive way) things that it has ever done.

I decided that fair use would make the most sense in this context. This was a book about an important modern artist. In addition, I’m a senior scholar—this was not my first publication. If the worst happened, if I had problems, well, I’ve had a great career and this would not harm it. I have tenure and so on. Also, as the then-president of CAA, I thought it was important to do this.

Besides, this to me was part of a larger picture of what I had done in my larger career. I’m very active locally in civic affairs, and really interested in promoting transparency, and democratic ideals. I was also very fortunate to have Peter Jaszi, a foremost legal scholar on fair use (and another principal investigator on the CAA project), working with me. At his suggestion, I took out an insurance policy, which for a fee—I think about $5,000—(with a $10,000 deductible) I was able to lower my anxiety level. I also paid $400 for an attorney to look over the insurance contract. And I had good friends like you, who when I got cold feet assured me it was the right thing to do. And of course, Duke is a publisher that has been willing to go ahead of others on fair use.

Can you give me an example of something you had to change in the text to strengthen the fair use argument?

With a museum photograph of an African mask, for example, I had to explain why this particular way of photographing the work was critical to the argument in my book. I had to ad a few sentences to justify my selection of several Picasso works as well. I also had to give reasons in my text for why each of the chapter epigraphs was necessary.

Did you have to alter the use of imagery in any way to accommodate fair use?

There are changes the press made, design-wise, that reflected in part the decision to employ fair use. Many of the photos are shown in black-and-white and the majority are reduced in size. I was constrained by the fact that I could only employ fair use if I could get access to the materials without going through the Picasso Foundation. So I had to acquire nearly all the images from published books, and many of the Picasso images were published in black and white and at a very small size, in a grainy context. I had to spend a lot of time hunting down the best possible images to use. In my book they are shown in relatively small size, along with information on where you can find color versions online.

That didn’t bother me too much, though. For readers and viewers at this juncture in the Internet era, we have become expert at extrapolating the fuller figure from a small image.

There is also a small spread of color images, a couple Picasso works as well as from other artists. For these images color was central to the book.

The decision to publish largely in black-and-white was, I think, also related to the fact that the Picasso Foundation and others are concerned that color representations be incredibly accurate, and it is very hard to get the color exactly right, when copying from books. You also have an issue with paper quality in getting accurate representation.

The cover is a handsome design, and very clever. They broke up the images into thumbnail-like sections, requiring you as a viewer to put them together as one image, similar to how Picasso was thinking in the early stages of cubism, where you as a viewer of an assemblage have to assemble them in your own mind, to make it work for you as a whole.

How was the book received?

It was a finalist for the Prose Prize, a prize of publishers to authors. My previous book won it in 2016. I didn’t expect to win it this time again, in 2019. I was very honored that it was a finalist. It was also featured in the Wall Street Journal’s holiday art book list. And then, just recently, it won the Robert Motherwell Book Award.

Has the Picasso Foundation seen the book?

To date I’ve heard nothing. I was thinking earlier that the Picasso Foundation might want to stop it pre-publication. So much so that when I came back from travel in Africa, I went first to my academic mailbox, and was relieved when I saw no big legal envelope. But there has been no pushback. I certainly gave them the opportunity to comment on the content while it was still in manuscript. And last April or May, I went to France to meet with the curators at Musée Picasso about contributing an essay to a catalog. I sent them an article draft which they decided not to publish, which is fine, but also sent them a copy of the manuscript, and of course the Musée speaks to the Foundation.

Interestingly, the two cases where the Foundation has sued or prevented publication that I know of have to do with children’s books about Picasso. I don’t know what that means.

Does the wider art history community know about this?

I hope this personal story makes a difference. We still have a lot of educating to do, in spite of the work we did around the Code. I continually get, on the art history listservs, questions—How can I get permission, and I always say, Use fair use. People still don’t trust it or believe it’s more difficult than it is.

At the CAA conference I just went to in Chicago, there seems to be a division between presses. Presses at private universities–Yale, Princeton, MIT, Duke—seem to feel more comfortable exploring this. But for university presses at some public institutions, these legal issues have to be taken up with the state attorney general, and there can be real nervousness stepping outside a narrow parameter. I learned this speaking to an editor at a state university press in a progressive state, who believes they’re being held back because of this fear.

I was pleased to see at this same conference a pamphlet on fair use by Duke University Press’s former Director, Steve Cohn. In his essay, he mentions my Picasso book and how happy he is that Duke chose to publish it this way. I figured, if Steve is openly talking about this fair use project, then the proverbial cat is out of the bag, and I could be more open and provide some of the back story from my end.

CAA’s scholarly publications, The Art Bulletin, Art Journal, and Art Journal Open rely on fair use as a matter of policy, and indicate when they do so in their photo credits. View a complete discussion of fair use and CAA’s Code of Best Practices.

CAA Fair-Use Events in Los Angeles and Saint Louis

posted by CAA — May 19, 2017

A scene from the fair-use workshop at the UCLA Library (photograph by Sharon E. Farb)

On May 5, 2017, CAA hosted “Fair Use and the Visual Arts,” a presentation and panel discussion at the UCLA Library. The event was made possible by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Speakers on the panel included Peter Jaszi, the lead investigator on the CAA Code of Best Practices in Fair Use in the Visual Arts and Professor at American University Washington College of Law in the Program on Information Justice and Intellectual Property, and Janet Landay, Program Manager of the Fair Use Initiative at CAA. The pair, who have given presentations across the U.S. and internationally as part of the CAA Fair Use Initiative, talked about why it was important for CAA to undertake the project, their methodology, and the resulting Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

The second half of the event was devoted to a Q&A with the audience of approximately fifty-five people. Question topics ranged from addressing the issue of how the size at which an illustration is produced impacts fair use to indicating in a caption or illustration credits section that I am claiming fair use in the reproduction of an illustration.

A second discussion on CAA’s Fair Use Initiative took place at the American Alliance of Museum’s 2017 Annual Meeting and MuseumExpo in Saint Louis, Missouri. The panel discussion, titled “Copyrighted Material in the Museum: A Path to Fair Use,” took place on May 9. The panel brought together esteemed colleagues from the museum and publishing worlds and was comprised of Patricia Fidler, publisher of art and architecture at Yale University Press; Anne Collins Goodyear, codirector of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art; Judy Metro, editor in chief for the National Gallery of Art; and Joseph Newland, director of publishing for the Menil Collection. Hunter O’Hanian, CAA executive director, was the chair and moderator.

A presenter at AAM’s annual meeting discussed Andrea Wallace’s Still Life Pixel + Metadata Dress (photograph by Anne Young)

About seventy-five to one hundred people attended the standing-room only session and discussion revolved around fair-use issues for museums who want to use their own materials: catalogues, brochures, websites—even wall texts. A key takeaway from the session: museum representatives need to maintain good relations with donor and lenders, and getting approval from their own legal counsel, who tend to approach these matters with caution.

Later in the day Hunter O’Hanian spoke to faculty and students in the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Washington University in Saint Louis.

Learn more about the CAA Fair Use Initiative

Learn more about the 106th CAA Annual Conference in Los Angeles, February 21-24, 2018

CAA Goes to France

posted by CAA — May 08, 2017

The College Art Association has been invited to speak about its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts at two conferences taking place in France in early June. On June 4 in Fontainebleau, executive director Hunter O’Hanian will participate in a session on “Fair Use and Open Content” at the seventh annual Festival of Art History, along with speakers from the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art (UK), the J. Paul Getty Trust, and the French Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art.

The College Art Association has been invited to speak about its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts at two conferences taking place in France in early June. On June 4 in Fontainebleau, executive director Hunter O’Hanian will participate in a session on “Fair Use and Open Content” at the seventh annual Festival of Art History, along with speakers from the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art (UK), the J. Paul Getty Trust, and the French Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art.

Two days later, on June 6, Hunter will join Peter Jaszi, lead principal investigator on the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, in Paris to speak at a session on fair use during the annual conference of ICOM Europe. They will be joined by speakers from England, France, and Germany, to discuss “Copyright Flexibilities in the US and EU: How Fair Use and Other Flexibilities are Helping Museums to Fulfill their Mission.”

Both conferences provide opportunities for CAA to share its work on fair use with EU visual arts professionals. Though this feature of copyright law is virtually unique to the United States, there is increasing interest in Europe to provide greater access to copyrighted materials, especially in the cultural sectors of these countries. Travel costs for CAA’s participation are underwritten by a generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Presentation on Fair Use at UCLA

posted by CAA — April 19, 2017

CAA is hosting “Fair Use and the Visual Arts,” a presentation and panel discussion led by Peter Jaszi, Professor, Washington College of Law, American University, on Friday, May 5, 2017. The event will focus on the College Art Association’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts and will take place at the UCLA Library from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM. Lunch will be served.

Come join the conversation! Please RSVP to give us your lunch preferences, and when you do, please share your specific Fair Use questions so our presenters can break it down for you.

For more information: https://www.library.ucla.edu/events/code-best-practices-fair-use-visual-arts.

This event is made possible by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

CAA Presents a Fair Use Workshop in Richmond

posted by CAA — April 10, 2017

Peter Jaszi speaks to participants at a fair use workshop in Richmond, Virginia, March 24, 2017.

On Friday, March 24, the University of Richmond Museums, Virginia, hosted a CAA Fair Use Workshop, co-sponsored with the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Statewide Program, and made possible with a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Elizabeth Schlatter, CAA Vice President for the Annual Conference, and Deputy Director and Curator of Exhibitions at the University of Richmond Museums, led the planning effort to bring over 40 artists, museum professionals, archivists, professors, librarians, and communications experts to the daylong workshop.

The program was led by Hunter O’Hanian, CAA’s Executive Director, and Peter Jaszi, Professor of Law at American University, and one of the two lead principal investigators on the project. After a round of introductions by attendees, Jaszi began the day with an introduction to the doctrine of fair use, followed by a presentation by O’Hanian about CAA’s four-year fair use initiative and the methodology employed to develop the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. The workshop continued with a focus on fair use in art museums, including when it can be invoked in exhibition projects, publishing, and online activities. During a working lunch, Jaszi and O’Hanian led discussions on reliance on fair use in teaching, publishing, and making art, and concluded the day with a discussion about fair use in libraries and archives.

Catherine G. OBrion, the Librarian-Archivist at the Virginia State Law Library, wrote afterwards, “I have a much better understanding of the legal standing of fair use, its intent, and how I can defend relying on it to my in-house counsel and others….One of the most useful workshops I’ve attended.” The workshop was followed by a reception at the University Museums for all CAA members in the local area.

CAA executive director O’Hanian also met with two University of Richmond classes the day before, one a museum studies seminar and the other a class on contemporary art and theory. The undergraduates benefited from O’Hanian’s advice on curating exhibitions, organizing public programs, surviving and thriving as a visual artist, and applying for artists’ residency programs.

Learning from Experience: Fair Use in Practice

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — March 14, 2017

We are eager to learn how individual CAA members are relying on fair use. Please take the following survey to let us know if, how, and to what extent you rely on fair use! Link here.

At last month’s Annual Conference, CAA’s Committee on Intellectual Property (CIP) organized “Learning from Experience: Fair Use in Practice,” a panel addressing fair use and how reliance on this aspect of copyright law has increased since CAA published its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts two years ago. The CIP session featured leading visual arts professionals in four areas: the academic art library, publishing, art-making, and artist-endowed foundations, each of whom described the importance of fair use in her work. The session, which was attended by more than ninety conference-goers, was led by CIP’s new chair, Anne Collins Goodyear, co-director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, and CAA president emerita, during whose tenure CAA undertook its fair use project, which culminated in the publication of the Code.

The panel opened with a brief overview of CAA’s fair use initiative by Goodyear, and then offered compelling examples of the Code’s application. Carole Ann Fabian, the Director of the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University reported that Columbia advances the principal of open access policy where possible, and that Avery librarians draw upon three fair use codes when advising library users about quoting from or reproducing copyrighted materials: that developed by the Association of Research Libraries (2012), CAA’s Code of Best Practices (2015), and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) Guidelines (2016). The shared norms of the CAA and AAMD codes, both of which champion a liberal assertion of fair use, provide particularly helpful guidance on fair use applications related to copyrighted images. Avery is often the first point of contact for students and faculty who have questions about these issues, and as a collecting organization, is also a provider of primary content (and their digital surrogates) to scholars worldwide. Fabian noted that the work librarians perform educating users about copyrights and the doctrine of fair use is ongoing with each year’s influx of new students and faculty. Having a concise resource like CAA’s Code, makes it infinitely easier to introduce library users to this essential feature of American copyright law.

Victoria Hindley, Associate Acquisitions Editor, MIT Press, reported that discussions about fair use at last year’s CAA Annual Conference motivated her to work with her colleagues at MIT Press to pursue a fair use initiative of their own. With support from Executive Editor Roger Conover, Press Director Amy Brand, legal counsel, and others, Hindley helped to define a progressive position in support of responsible fair use. “One of our primary goals,” she said, “was to figure out how to reduce the burden of clearing permissions placed on the author.” The resulting proposal, which is undergoing final Institute approval, is a robust document that most notably, as she explained: “would no longer require authors to indemnify the press when they have made a reasonable good faith determination of fair use.” MIT Press has developed proposed new contract language in support of this position; and, to further empower authors, the Press has crafted permissions guidelines that take advantage of the CAA Code and also refer authors to it. “The CAA Code of Best Practices has proven to be an invaluable guide for us as we’ve held these discussions and made decisions about our own guidelines,” noted Hindley. The new policy pending adoption at MIT Press would provide protections similar to those that CAA grants contributors to its publications.

The third speaker was the distinguished artist Martha Rosler, who received a Lifetime Achievement Award during the conference from the Women’s Caucus for Art. Rosler has for decades incorporated into her work images circulating in what she has called the public sphere of mass media, including newspapers, magazines, and television, without stopping to consider copyright. While showing examples of her work, Rosler described the importance of processes like hers, which, she said, for many artists “constitute an essential form of critique.” Although Rosler’s practice predates the publication of CAA’s Code of Best Practices, she acknowledged that the Code serves to clarify the principles on which such a practice is based. She also noted that the Code has the potential to offer support and encouragement to other artists who might otherwise shy away from the legitimate use of copyrighted material in their work, for fear of adverse consequences. She also observed, with regret, that many artists, particularly those working in video, have deliberately abandoned or failed to undertake projects involving appropriation precisely because the legal departments of broadcast entities bar the airing of such works, out of fear of reprisal for purported infringements.

Francine Snyder, Director of Archives and Scholarship at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, was the fourth speaker in the CIP session. She talked about the positive effect on the Foundation of a proactive fair use policy in the year since it was introduced. The main goal of the policy has been to foster scholarship about Rauschenberg, disseminate knowledge, and enhance educational initiatives. In this regard, Snyder reported, the policy has proven a great success, generating more scholarship and innovative projects. Among the outcomes to which she referred is an online gallery for children that includes images of Rauschenberg’s work. Snyder indicated that one of the most important values of the Foundation’s public turn to fair use has been to reduce anxiety on the part of those who want to reproduce the artist’s work for creative and scholarly purposes. Snyder mentioned that the fair use policy does not apply to commercial uses, for which the Foundation relies on licensing through VAGA. By way of conclusion, she explained that the Foundation is committed to an open dialogue as interpretations of fair use continue to evolve, as seen in the multiple applications of CAA’s Code of Best Practices.

Following the formal presentations, Jeffrey P. Cunard, CAA’s counsel, and Co-Chair of its Fair Use Task Force, moderated a discussion with the speakers and audience. Cunard noted the importance of the Rauschenberg Foundation’s turn to the doctrine of Fair Use in making work by Rauschenberg available for scholarly and creative purposes, and the relationship between fair use and an open approach to licensing images. He also clarified, in conversation with Rosler, that copyright holders had not objected to her pioneering work, which may not have been surprising, given the transformative nature of her use of appropriated material.

The talks by each of the speakers on this panel, along with the great interest expressed by the audience, point to increased awareness of the application of fair use since CAA published the Code of Best Practices two years ago. While detailing the many ways in which fair use is benefitting scholarship and creative practice, the session also makes clear the need for ongoing education about the Code, and the importance of publicizing and encouraging its use. We invite further examples of fair use in action, and any suggestions for the continued dissemination of the Code and the guidance it provides.

A CAA Road Trip

posted by Janet Landay, Program Manager, Fair Use Initiative — October 18, 2016

Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine (photograph by Janet Landay)

Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine (photograph by Janet Landay)In late September, Hunter O’Hanian and I had the pleasure of spending a weekend at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, to attend two CAA events hosted by Anne Goodyear, codirector of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and a former CAA president. We arrived at the picturesque New England campus on a beautiful fall day. The college’s art museum, one of the oldest in the country, anchors the western edge of the quad, its neoclassical façade presiding gracefully over green lawns and majestic trees where students played Frisbee, read, or walked across campus. It was a perfect weekend to welcome CAA members to campus.

The first group arrived that Saturday afternoon to attend a CAA member reception, the first of several Hunter has planned around the country to provide an opportunity for him to meet with members in a relaxed setting and talk about CAA. The event began with a tour of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art given by Anne and her husband, the museum’s codirector, Frank Goodyear. Immediately following, we all walked a block away to Anne and Frank’s house to enjoy some wine and cheese on their back patio. The fifteen or so participants hailed from several schools and museums in addition to Bowdoin—Colby College, Bates College, the Portland Museum of Art, and the Farnsworth Art Museum—and included art historians, artists, librarians, and independent scholars.

Members spoke in turn about their most memorable CAA experiences: attending a first conference, interviewing and getting a job, meeting old friends, or networking with scholars in their fields. Hunter then shared thoughts about his goals for CAA based on what he has learned from members since he became executive director in July. He observed the importance of connectivity—how to keep CAA members in touch with issues in the field, but especially how to keep them in touch with each other. And he described many of the changes members will experience at the next Annual Conference, including a focus on personal experience, captured by a new theme for the meetings, myCAA.

On Sunday morning, several of the same CAA members returned, joined by others from around the state, for a half-day workshop about copyright and fair use. Peter Jaszi, a co–lead investigator on CAA’s Fair Use Initiative, came from Washington, DC, to Bowdoin to lead the program, which focused on how visual-arts professionals can use CAA’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts in their work. Following an introduction to copyright and fair use, the workshop began with a look at how museum professionals can use the Code when employing copyrighted materials in their work.

Participants had been asked to bring real-life questions with them. Thus, a museum director wanted to know whether his museum could allow photography in the galleries of works still protected by copyright. A curator described a challenge she had in getting an image for a catalogue from a museum in central China. When she received no reply from the museum, she resorted to scanning the image from another book. Is that fair use? Other questions involved loan forms, credit lines, and online projects.

As the day continued, the program moved on to address questions from professionals in other areas: librarians and archivists, professors and teachers, artists and independent scholars. Can a faculty member use images in class that she got from a flash drive she had received from a foreign museum? What kind of credit information is necessary for a blog about films? Is Shepard Fairey’s image of Obama a good case study for students learning about fair use? How should the institutional repository on a college campus view the copyright protection of yearbook photographs? By the end of the afternoon, a remarkable range of questions had been discussed, and the forty participants came away with a much greater understanding of fair use and how to rely on it in their work.

Peter Jaszi and Kyle Courtney at CAA’s fair-use town hall at Harvard University (photograph by Janet Landay)

Peter Jaszi and Kyle Courtney at CAA’s fair-use town hall at Harvard University (photograph by Janet Landay)On Monday, Hunter, Peter, and I were in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to join Kyle Courtney, a copyright specialist in Harvard’s Office for Scholarly Communication, for a fair-use town hall on the campus of Harvard University. As in Maine, Peter began the program with an introduction to fair use, and I followed with a description of CAA’s Fair Use Initiative. Kyle spoke about a program he directs at Harvard that trains librarians to be “first responders” to users’ questions about fair use. Although relatively new, the program has proven to be an effective way to support and teach visual-arts professionals about fair use. It is now being replicated on other university campuses. The event was then opened to questions from the sixty-five members of the audience, which Peter and Kyle discussed in depth.

Many of the topics were similar to those that had been addressed at the Bowdoin workshop, but a new subject emerged as well: advocacy. Does a professor who has had a manuscript accepted have any recourse when her publisher requires signed author agreements stating that all images had been cleared for publication and all fees paid? The answer is yes; she can ask her publisher to read CAA’s Code and explain that many, if not all, of her uses of images comply with the doctrine of fair use. While the effort may not succeed (though CAA has several success stories on file), over time it will familiarize publishers with the principles outlined in the Code. Changes have already taken place, in large part due to this kind of challenge from users. Yale University Press now accepts fair-use defenses from its authors who are publishing monographs; the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation embraced a fair use policy for that artist’s work; and CAA not only encourages its authors to consider whether or not their uses are fair, but it also indemnifies authors against lawsuits about works used under fair use.

The program concluded with a reminder that CAA is happy to answer questions about fair use; please don’t hesitate to contact us at nyoffice@collegeart.org.

The CAA member reception at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (photograph by Janet Landay)

The CAA member reception at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (photograph by Janet Landay)Later on Monday, Hunter and I joined another group of CAA members at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design for a wine-and-cheese reception at the school’s President’s Gallery and Bakalar and Paine Galleries. Attendees included a wide range of members, from professors who have belonged to the association for thirty years to new members just graduating from MFA programs. Lisa Tung, the gallery’s director and curator, kicked off the event with a tour of two exhibitions currently on view, Encircling the World: Contemporary Art, Science, and the Sublime and Women’s Rights Are Human Rights: International Posters on Gender-Based Inequality, Violence, and Discrimination. Hunter, who is a former vice president for development at MassArt, then invited participants to speak about how CAA is valuable to them. He emphasized the importance of hearing from members so that CAA can support them as fully as possible in this rapidly changing world.

CAA’s road trip continued in early October with another member’s reception in Portland, Oregon. Later this month we will convene a fair-use workshop in Seattle, Washington. More events are planned for early next year in Georgia and Virginia. Stay tuned!

The Bowdoin College fair-use event was organized by the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and CAA, with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The Harvard University fair-use event was organized by Harvard’s Office for Scholarly Communication, thanks to the generous support of the Arcadia Fund, and by CAA, with funds provided by the Mellon Foundation.