CAA News Today

International Review: The Many Faces of Human Impacts in The Seventh Continent, 16th Istanbul Biennial

posted by CAA — Dec 17, 2019

THE MANY FACES OF HUMAN IMPACTS: Exhibition Review of The Seventh Continent, 16th Istanbul Biennial, curated by Nicolas Bourriaud, September 14–November 10, 2019.

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Madeleine Kelly, an artist based in Sydney, Australia.

When artists work with archaeology and anthropology it is easy to imagine their work as a labor entrenched in the past. Yet, in the 2019 Istanbul Biennial—an enormous exhibition in three venues that presented the work of fifty-six artists and art collectives from twenty-six countries—artists engaged with the descriptive capacity of archaeological methods by reinvesting them in the metaphorical dimension of imaginative artifacts and languages. New and complex ways of signifying humanity’s traces, marks, and interactions with the non-human universe emerged, blurring the traditional separation between nature and culture. Following from this, the division between subjects and objects also breaks down, granting subjective agency to stones, plants, and other non-human voices. The most powerful works invented an “inter-subjective relation” (see discussion below) that proceeded by way of the form of the face. As othered subjects are often faceless, the mediums in which they are embodied configure them as anthropological concepts. Entitled The Seventh Continent after the drifting mass of plastic waste that contaminates the world’s oceans, this year’s Istanbul Biennial explored the complex entanglements of anthropogenic climate change and the human impact on the planet.

French curator and art historian Nicolas Bourriaud is known for his controversial book, Relational Aesthetics (1998, English translation 2002), which revitalized the discussion on aesthetics at the time. In it, film critic Serge Daney suggested that the invention of “inter-subjective relation” proceeds by way of the form of the face, an exchange that denotes the consideration we have towards others. Further, to produce a form is to partake in a transitive ethic in which an image mediates the longing to be looked at. He states that “all form is a face looking at me.” In the biennial, Bourriaud drew attention to “the primacy of encounter over form,” arguing that dynamic encounters between different types of beings–and by extension forms–constitute relational formations. I propose that an echo of his early citation of inter-subjective relation is present in forms with subject-like qualities–in particular faces– and that these especially address our relation to dwindling diversity and mounting waste generated by industrial capitalism.

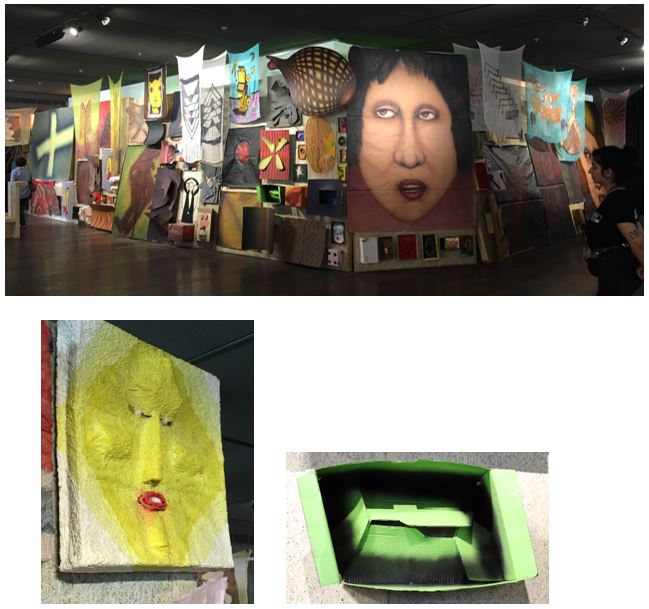

Figure 1: HaZaVuZu art collective, Worlbmon, 2019, installation view and details; Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture (photograph provided by the author)

In the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture, located in the heart of the city, the Istanbul-based HaZaVuZu art collective presented an alluring grotto-like installation of animated surfaces and faces inspired by everyday packaging, inkblots, and grotesque figures that “look back at us” (Fig. 1). The myriad images recall the semiotic wonderland of Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia Museum, weaving its historical thread of the iconophilic and iconoclastic, but the HaZaVuZu seems to riff on this legacy with forms that oscillate between iconic, indexical, and symbolic sign systems. Bourriaud’s statement (in an introduction to the exhibition) that “the work of art is a signal, akin to those all living organisms emit” seems to crystalize in these works where the artists breathe life into inanimate materials composed of matter seemingly evolving into being.

Figure. 2: Hale Tenger, Appearance (detail), 2019, mixed-media and sound installation, black obsidian mirrors, iron, epoxy resin based paint, water, audio-spotlight speaker, Büyükada Island (photograph provided by the author)

Along with the trope of the living work is that of art as a mirror to the world, reflecting the ineffable operations of nature. Yet in the context of the exhibition, an ideal nature is displaced to expose, as Bourriaud states, “the reverse mirror-image of our societies, the seventh continent is the country we don’t want to inhabit, made up of everything we reject.” On the island venue of Büyükada, a ferry ride from town, Istanbul-based artist Hale Tenger presented a mixed-media and sound installation entitled Appearance (Fig. 2). The viewer entered an apple orchard on the grounds of the dilapidated Sophronius Palace in which round black obsidian mirrors and pools of water reminiscent of black oil reflected skyscapes and trees. A voice from the house hoarsely whispered a poem by the artist: “I was a fruit tree . . . I gave, without expecting reciprocity . . . can you be by not doing?” And when we saw our faces reflected in the black mirrors we felt caught up in the quotidian complicities conjured by the question.

Another compelling work, this time the face of the deep, was also on the island. Armin Linke’s investigative film Prospecting Ocean (2018) transported viewers to the world of deep-sea politics where activists organize protests against seabed mining and the technocratic entanglement of industry, science, politics, and the economy. In the accompanying installation of documents related to Italian and Turkish marine history, a book chapter entitled “Ion by Ion,” by marine scientists Bruce Heezen and Charles Hollister, beautifully describes the evolution of mineral gardens comprised of manganese nodules. These polymetallic rock concretions accumulate daily in atomic layers and correlate with species abundance. Like strata that accumulate in the layers of a painting, the nodules embody an enlivening vitality.

Figure 3. Mika Rottenberg, still from Spaghetti Blockchain, 2019, 4K color video installation with 7.1 surround sound, 18:15 min.; Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture (artwork © Mika Rottenberg; photograph provided by the artist and Hauser & Wirth)

Artist Mika Rottenberg’s rapid-edit video Spaghetti Blockchain presents more strata, but hers are of oozy plastic modelling compounds, cakes that accumulate in layers of artificially coloured jelly, and molecular models scaffolded from skewers and marshmallows (Fig. 3). The film cuts to a potato-processing plant that rips through tree branches and thousands of potatoes in granular form. The agency of the hand appears as a critical element, often framed by hexagonal kaleidoscopic apertures that “blink” us through the brilliantly edited comic nightmare of her “organic chemistry.” Bourriaud proposes, “today’s artists practice a type of anthropology that one could call molecular.”

Figure 4: Eloise Hawser, Feathering, 2019, video sculpture, 76 x 101 x 20 in. (193.6 × 257 × 50 cm), steel, laminated and repurposed glass panels, Pera Museum (photograph provided by the author)

Another work, The Tipping Hall by London-based artist Eloise Hawser, takes the “petal claw” as its subject. These mechanical fists, with their twenty-six foot (eight meter) talons, do a vital job of aerating the waste of tipping halls to prevent the build-up of toxic gases. This work was displayed in the biennial’s third venue, the Pera Museum, as was Hawser’s Feathering (2019), a mesmeric kinetic sculpture made from waste and showing, at high magnification, the intricate and fine-toothed handling of e-waste (Fig. 4).

Figure 5: Jonathas de Andrade, still from O Peixe (The fish), 2016, 16mm transferred to 2K video, 5.1 sound, screen ratio 16:9 (1.77), 23 min.; Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture (photograph provided by Pedro Urano)

In Brazilian-based artist Jonathas de Andrade’s film O Peixe (The fish) (Fig. 5), Amazonian fishermen ceremoniously embrace and caress their slowly suffocating catch. While stylistically a pastiche of early ethnographic films, the intimate gesture between man and dying fish is an invention of the artist. Pertinent here is the aesthetic encounter between humans and animals being slaughtered, generating uneasy discussions and making this a challenging work.

In many ways, The Seventh Continent was an aestheticizing of the anthropogenic environmental tragedy. These artists translated notions of subjectivity into forms that document and/or question human impact–their forms look back at us, urging us to explore the complex entanglements of anthropogenic climate change and holding us to account for our impact on the planet.