CAA News Today

Monica Zandi and Stephanie Cortazzo

posted by CAA — February 11, 2019

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

CAA podcasts are on iTunes. Click here to subscribe.

This week, Monica Zandi and Stephanie Cortazzo discuss “Body/Cut” and the Brooklyn Collage Collective.

Monica Zandi is a writer, educator, and graduate art student at Hunter College.

Stephanie Cortazzo is a multimedia artist who recently had a show entitled Cosmic Crisis and is in the Brooklyn Collage Collective (www.brooklyncollagecollective.com/).

Submit Your Work to ARTexchange at CAA 2019

posted by CAA — January 23, 2019

Artist Joanne Tarlin presents her work at ARTexchange at the 2018 CAA Annual Conference in Los Angeles. Photo: Rafael Cardenas

The Services to Artists Committee invites artist members to submit work to ARTexchange, CAA’s pop-up exhibition and annual social event for artists and curators. This event provides an opportunity for artists to share their work and build affinities with other artists, historians, curators, and cultural producers. ARTexchange will take place Friday evening, February 15, 2019, from 5:30–7:30 PM, and is free and open to the public.

Participating CAA members will be given space to share their work on, above and beneath a six-foot table. Artwork cannot be hung on walls, and it is not possible to run power cords devices. Participants are responsible for their own work. Sales of work are not permitted. Performance, process-based, interactive, and participatory works are especially encouraged.

Please be sure to provide all of the following information in order to complete your submission:

- A short biography or artist statement. (150 words max)

- A description of what you will exhibit and how you will use the space. Please include any details regarding performance, sound, spoken word, or technology-based work, laptop/tablet digital or media presentations. (250 words max)

- Your CAA member number (memberships must be valid).

- A link to a website of your work or 5-10 images of your recent work, including: title, year, medium and dimensions. (Maximum image size 5 mb of 1500pixels largest size and sent as JPG)

Submissions to ARTexchange can be and sent by email to Julie Hughes (artexchangeCAA@gmail.com) with “ARTexchange” and your last name in the subject line.

Deadline to submit: February 1, 2019

CAA Announces Notable Speakers for 2019 Annual Conference in New York

posted by CAA — December 03, 2018

Artist Joyce J. Scott leads as Keynote; Distinguished Scholar Elizabeth Hill Boone; Artist Interviews with Julie Mehretu and Julia Bryan-Wilson and Guadalupe Maravilla and Sheila Maldonado; Designer Stephen Burks, and Douglas Dreishpoon and Randy Kennedy with Mary Helimann, Bob Stewart, and John Giorno, among many other notable speakers and presenters

The Getty Foundation to receive the Outstanding Leadership in Philanthropy Award

We’re delighted to announce the following special guests will be presenting at the 107th CAA Annual Conference, taking place February 13-16, 2019, at the New York Hilton Midtown.

Keynote Speaker

Joyce J. Scott. Photo: John Dean

The Keynote Speaker for the 107th CAA Annual Conference will be Joyce J. Scott, sculptor and craftsperson and 2016 MacArthur Fellow. Scott is best known for her figurative sculpture and jewelry using free-form off-loom bead weaving techniques similar to a peyote stitch, as well as blown glass, and found objects. Over the past 50 years, Scott has established herself as an innovative fiber artist, print maker, installation, and performing artist. She explores challenging subjects, powerfully revealing the equality between materials and practices often associated with “craft” and “fine art.”

Scott is the recipient of myriad commissions, grants, awards, residencies, and prestigious honors from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation, Anonymous Was a Woman, American Craft Council, National Living Treasure Award, and has received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Women’s Caucus for the Arts, a Mary Sawyers Imboden Baker Award, among others.

CAA Convocation featuring Joyce J. Scott’s Keynote will take place Wednesday, February 13, 2019, from 6-7:30 PM. Free and open to the public.

Elizabeth Hill Boone. Photo: Paula Burch

Distinguished Scholar

The Distinguished Scholar for the 107th CAA Annual Conference will be Elizabeth Hill Boone, Professor of History of Art and Martha and Donald Robertson Chair in Latin American Art at Tulane University. An expert in the Pre-Columbian and early colonial art of Latin America with an emphasis on Mexico, Professor Boone is the former Director of Pre-Columbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks and recipient of numerous honors and fellowships, including the Order of the Aztec Eagle, awarded by the Mexican government in 1990. Read our interview with Elizabeth Hill Boone.

The Distinguished Scholar Session will take place Thursday, February 14, 2019, from 4-5:30 PM.

Distinguished Artist Interviews

The Annual Artist Interviews will feature two artist interviews: Julie Mehretu interviewed by Julia Bryan-Wilson and Guadalupe Maravilla interviewed by Sheila Maldonado.

Julie Mehretu. Photo: Anastasia Muna

Julie Mehretu is a world-renowned painter, born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 1970, who lives and works in New York City and Berlin. She received a Master’s of Fine Art with honors from The Rhode Island School of Design in 1997. Mehretu is a recipient of many awards, including the The MacArthur Fellowship (2005) and the US Department of State Medal of Arts Award (2015). She is best known for her large-scale paintings that take the abstract energy, topography, and sensibility of global urban landscapes and political unrest as a source of inspiration. She has shown her work extensively in international and national solo and group exhibitions and is represented in public and private collections around the world. Julia Bryan-Wilson is Doris and Clarence Malo Chair and Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at University of California, Berkeley.

Guadalupe Maravilla. Photo: Raul Rodarte Torres

Guadalupe Maravilla (formally Irvin Morazan) was part of the first wave of undocumented children to arrive at the United States border in the 1980s from Central America. In 2016, as a gesture of solidarity with his undocumented father (who uses Maravilla as his last name in his fake identity) Irvin Morazan changed his name to Guadalupe Maravilla. Maravilla has performed and presented his work extensively in venues such as the Whitney Museum of American Art, New Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Bronx Museum, El Museo Del Barrio, Jersey City Museum, Caribbean Museum (Colombia), and MARTE Museum (El Salvador). His work has been recognized by numerous awards and fellowships including, Franklin Furnace, Creative Capital Grant, Joan Mitchell Emerging Artist Grant, Art Matters Grant & Fellowship, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Fellowship, Dedalus Foundation Fellowship and the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Sheila Maldonado is a New York-based writer and poet, whose family hails from Honduras.

The Distinguished Artist Interviews will take place Friday, February 15, 2019, 3:30-5:30 PM. Free and open to the public.

CAA Committee on Design Featured Speaker

Stephen Burks. Photo: Photography Emin

CAA is also pleased to announce that designer Stephen Burks will speak at the Annual Conference in a special event of the CAA Committee on Design. Burks will lead a talk titled, “Objects of African Descent: Tracing the lineage and influence of everyday African objects and culture throughout the diaspora and beyond.” Burks believes in a pluralistic vision of design inclusive of all cultural perspectives. For his efforts with artisan groups around the world, he has been called a design activist. His ongoing Man Made project bridges the gap between authentic developing world production, industrial manufacturing, and contemporary design. Independently and through association with the nonprofits Aid To Artisans, Artesanias de Colombia, the Clinton Global Initiative, Design Network Africa, and the Nature Conservancy, Burks has consulted on product development with artisan communities throughout the world. In addition, leading, manufacturers have commissioned his studio, Stephen Burks Man Made, to develop lifestyle collections that engage hand production as a strategy for innovation. In 2015, Burks was awarded the National Design Award in product design and in 2018, the Harvard Loeb Fellowship.

UPDATE, January 28, 2019: Unfortunately due to scheduling conflicts this event is canceled. Explore other presentations on design here.

Outstanding Leadership in Philanthropy Award

For the second year, CAA will present the Outstanding Leadership in Philanthropy Award to a foundation or philanthropic organization that has established a record of exceptional generosity and civic and charitable responsibility. This year’s award will be given to the Getty Foundation.

Natasha Hovey and Steve Hilton

posted by CAA — November 05, 2018

The weekly CAA Conversations Podcast continues the vibrant discussions initiated at our Annual Conference. Listen in each week as educators explore arts and pedagogy, tackling everything from the day-to-day grind to the big, universal questions of the field.

CAA podcasts are now on iTunes. Click here to subscribe.

This week, Natasha Hovey and Steve Hilton discuss a yearlong artist residency model at Midwestern State University.

Natasha Hovey is currently an assistant professor at Texas A&M International University in Laredo, Texas, where she teaches: Ceramics 1, Intermediate and Advanced Ceramics, Sculpture 1, Intermediate and Advanced Sculpture, and Practicum Course for Seniors. She never thought she would miss it, but she longs for the Midwest’s subzero temps and feet of snow.

Steve Hilton is a professor of art at the Lamar D. Fain College of Fine Arts at Midwestern State University in Wichita Falls, Texas, teaching both Ceramics and Art Education. He just found out that the current MSU ceramics resident has been offered a full-time position, which means the MSU residency program is 6 for 6 in placing residents.

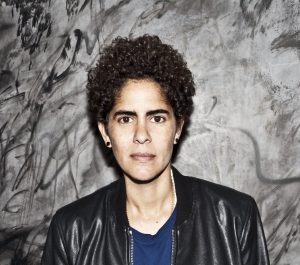

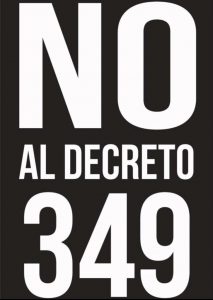

Tania Bruguera on Decree 349, the Criminalization of the Arts in Cuba, and How You Can Help

posted by CAA — October 18, 2018

In July 2018, the Cuban government issued Decree 349, legislation targeting the artistic community on the island nation. Under the decree, all artists—including collectives, musicians, and performers—will be prohibited from operating in public or private spaces without prior approval by the Ministry of Culture. It is slated to go into full effect on December 7, 2018.

CAA released a statement of opposition to the decree last month. Recently, CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske corresponded with artist, activist, and 2016 CAA keynote speaker Tania Bruguera to learn more.

Tania Bruguera delivers the keynote address at the 2016 CAA Annual Conference in Washington, DC.

Joelle Te Paske: I’ve read that Decree 349 was signed in April and then announced without any consultation on July 10 in the government’s newspaper. How did you first find out about it?

Tania Bruguera: Decree 349 was signed by the new President of Cuba [Miguel Díaz-Canel] without consulting artists—something even the national newspaper had to admit in a recent article, which was ironically published to defend the decree. Also, it was not publicly known until almost six months after it was official, but that didn’t stop them from [moving to] apply it. It was used already with younger artists who participated in the alternative biennial when recording their artist ID registration, the only legal document that protects and allows someone to be an artist in Cuba. They also enforced it with us at the Instituto de artivismo Hannah Arendt (Hannah Arendt Institute of Activism), charging fines of $2,000 for not having permission from the Ministry of Culture to do what they call “artistic services” inside of my house. The last free space we had in Cuba was our homes—now with this law, they are also regulated spaces.

JTP: The decree is wide-ranging and applies to all cultural activity, not just visual art, is that right?

TB: Yes, they are cutting all the heads. There is a strong independent cinema movement, an alternative music scene, DIY theater, and new independent art galleries—they are all going to be gone. The government is presenting this decree as an innocent regulation, but it is in fact a muzzle to artists. We know that those permissions are not based on anything but ideological considerations, and it will be used as a blackmailing instrument. Also, it gives the government the right to decide who is and who is not an artist, what is and what is not art.

JTP: Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, Amaury Pacheco, Iris Ruiz, Soandry Del Rio, and José Ernesto Alonso—artists who organized a protest performance on July 21—were arrested by Cuban police officials and charged with public disorder. Are tactics like this being used to intimidate artists who are speaking out?

TB: When you are protesting, when you get detained, you have already overcome your fears. In my experience, those repressive acts from the government consolidate your ideas. Confronting injustice unifies the group and makes people even more committed to fight. These detentions are designed to discourage by suggesting that your actions won’t change anything. They try to back you away from doing bigger collective demonstrations. Their absurd repression and disproportionate reaction to any small action shows how they are proving themselves wrong. But the real goal of all these engineered scare tactics is to intimidate those who are not protesting.

JTP: The decree specifically targets independent artists working without larger financial support structures. How do you think this will affect cultural life in Cuba?

TB: It is not a matter of finances at least for now—[the government] may use the same tactic of fake tax evasion charges that the Chinese government has used later on. Decree 349 also affects independent cinema which, comparatively, works with a larger budget. It is a matter of stopping artists from imagining, producing, and showing art independently. It is about the Ministry of Culture looking obsolete because it cannot control its artists, and so the law is intervening.

JTP: Amnesty International has written: “The lack of precision in the wording of the decree opens the door for its arbitrary application to further crackdown on dissent and critical voices in a country where artists have been harassed and detained for decades.” Would you agree with their assessment?

TB: Absolutely. This is the real goal of Decree 349—it even says that the artworks must follow ethical and revolutionary principles, but those are not described anywhere in the text nor linked to any other document to be consulted. In case you want to do your art “within the law,” there are no guidelines. “You should know better” and “Be submissive and compliant to the government’s needs of the moment” seem to be the subliminal messages.

What the artists who now have the favor of the government do not see is that the permissive line always moves. Today they are within the law, tomorrow they may be outside of the law. Everyone is a potential dissident in the eyes of the Cuban government—they do not trust anyone, and less so artists.

JTP: CAA recently put out a statement of support for the artists and activists opposed to Decree 349. What advice would you give CAA members who want to help?

TB: I want to thank CAA for its support of our cause. It makes an immense difference because the Cuban government makes a lot of its internal decisions based on how they make them look internationally. Our only protection comes from organizations and people in the world who recognize our experiences beyond all the official propaganda. It is important that people, especially those who identify as leftists and progressives, realize that Cuba today is not the one from the 1960s, where it was full of humanistic promise. Now we have a Cuba where the law is not to establish justice, but to measure the loyalty to the government.

The “Cuban legal turn,” as I call it, is an effort of the government to look “respectable” while abusing its power. They have found the perfect tool, one that is universally understood: the outlaws. No more conversations about politics or sympathies for you—now you are a common criminal. The Cuban government doesn’t recognize political prisoners. You are accused of some common crime instead of the real one, which is political. This makes it murky for people to understand what is happening and to be able to show solidarity. The conversation will shift from political rights to if anyone has ever seen the person in question taking drugs, stealing, molesting someone, or making a public scandal. Doubt then takes over your judgement [as the onlooker], and you may think twice before supporting a freedom fighter because you feel uncomfortable about the issues they are falsely accused of. That’s all the Cuban government needs from you, the ones outside of Cuba, the ones who can put pressure on them. That is why no dissident, and now no artist, will be ever accused of political motivation but rather for criminal offenses. What people need to know is that Decree 349 is not a law, but a way to stop the growing unified artistic movement for freedom of expression in Cuba. They need to understand that the law in Cuba is selectively applied to those uncomfortable to the government.

In these times, when totalitarian efforts are shamelessly growing around the world—specifically in the United States with Trump—we cannot get tired in front of injustice. We can’t forgive any injustice, no matter how small, because the next one is built on top off it.

JTP: Thank you. And to let our readers know, what are the projects you yourself are working on currently?

TB: I’ve been working on the Turbine Hall commission at the Tate Modern, which will be on view until February 24th, and on some new artworks to be shown in India, Italy, the UK, Sweden, and Mexico. I also just launched a new series of works focused on Trump and will soon do some new performances against Decree 349.

JTP: Anything else you would like people to know?

TB: Cuban artists are leading the fight for freedom of expression and we are not going to stop.You can support us by joining our petition to abolish Decree 349. Click here to sign.

Thank you!

CAA Opposes the Cuban Government’s Decree 349 and Its Impact on Artists

posted by CAA — September 05, 2018

Cuban artists and activists organizing in opposition to the decree. Image: Courtesy Yanelyz Nuñez Leyva via Hyperallergic

In July 2018, the Cuban government issued Decree 349, aimed at the artists’ community on the island nation. The decree is slated to go into effect on December 1, 2018.

The law will criminalize independent artists who do not have authorization from the Ministry of Culture, and it will empower a new cadre of state agents to shut down events, confiscate artists’ equipment and property, impose heavy fines, and make arrests. Cuban artists were not consulted in the development of the decree and will have no recourse to independent arbiters in the event of a dispute. In particular this legislation will affect artists who are black and poor, as well as independent artists.

Amnesty International recently issued a statement about Decree 349:

“Amnesty International is concerned that the recent arbitrary detentions of Cuban artists protesting Decree 349, as reported by Cuban independent media, are an ominous sign of things to come. We stand in solidarity with all independent artists in Cuba that are challenging the legitimacy of the decree and standing up for a space in which they can work freely without fear of reprisals.”

CAA supports the work of Cuban artists and activists inside and outside of Cuba in their campaign to urge the Cuban government to reconsider the law and agree to a public debate with the artistic community. We support the artists’ Open Letter urging the Cuban government to refrain from imposing these harsh restrictions on its artists.

Related: As Criminalization of the Arts Intensifies in Cuba, Activists Organize (Hyperallergic)

Tania Bruguera and Other Artists Are Protesting a New Cuban Law That Requires Government Approval of Creative Production (artnet News)

An Interview with 2018 CAA Distinguished Artist Awardee Pepón Osorio

posted by CAA — February 06, 2018

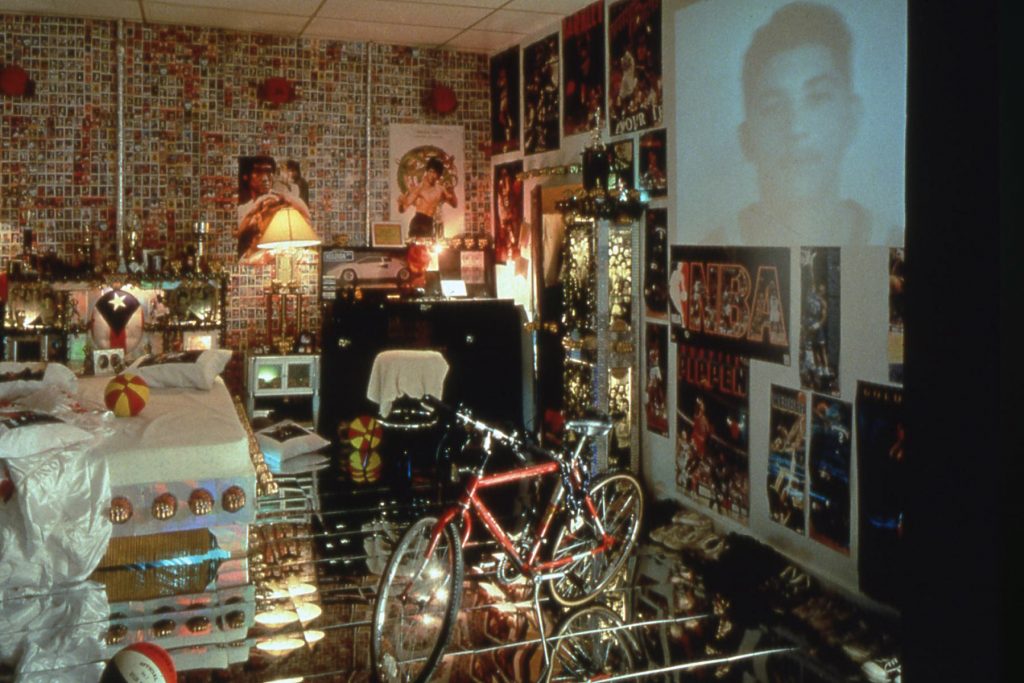

Pepón Osorio, Badge of Honor, 1995. Photo: Sarah Welles

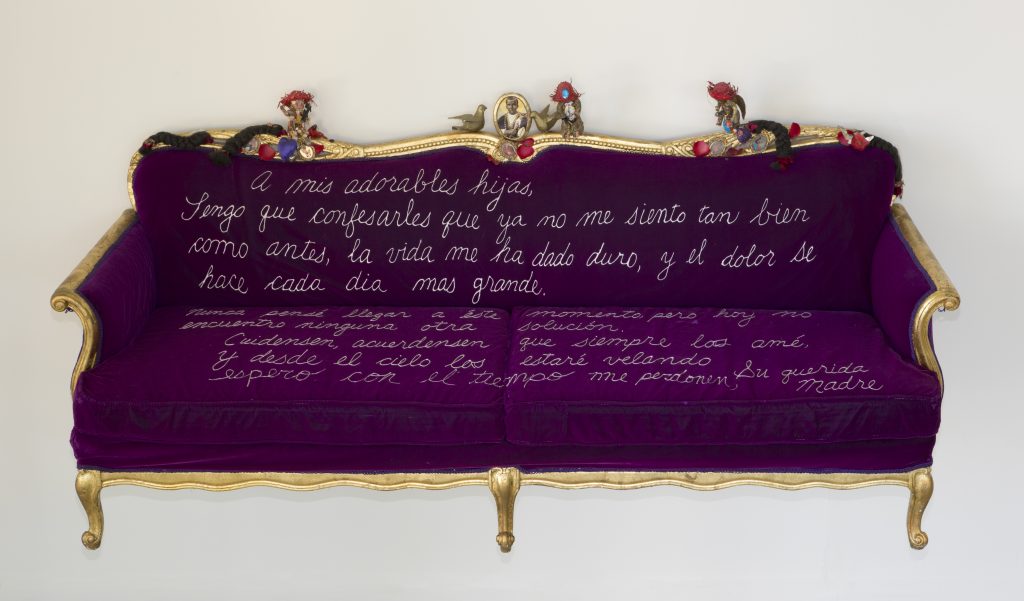

Drawing on his childhood in Puerto Rico and his adult life as a social worker in the Bronx, artist Pepón Osorio creates meticulous installations incorporating the memories, experiences, and cultural and religious iconography of Latino communities and family dynamics. The 2018 CAA Distinguished Artist Awardee for Lifetime Achievement, Osorio is a professor in the Community Arts Practices Program at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University. He is also the recipient of a 2018 United States Artists Fellowship, among many other awards and fellowships.

CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske worked with Pepón in 2016 on reForm, a project responding to school closures in Philadelphia in collaboration with students, teachers, and Temple University. In the project high schoolers, affectionately nicknamed “Bobcats” after their former school mascot, were invited to contribute to an art installation at Tyler School of Art, where they also met with local politicians to advocate for community-based school reform.

Joelle caught up with Pepón in January 2018 to hear his thoughts on being an artist and professor, and to learn about his hopes for the year ahead.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pepón Osorio, To my darling daughters, 1990. Photo: Carlos Avedaños

JTP: I’m happy to be speaking with you. When I heard that you were getting the award, it was great news!

So, we find ourselves in 2018—how are you doing? What’s on your mind?

PO: I think that I am still processing the fact that we are in 2018 and 2017 didn’t look very good for us. Both as an artist and a citizen. I’m hoping that we begin to tell the truth in a country of lies. I hope that is what 2018 is like. This is a very interesting moment with the CAA lifetime achievement award, because I’ve been mostly thinking in retrospect. How in the world did we get here? How did we get here and how did this happen?

I’m looking in retrospect and trying to see where energy is stored and how to rejuvenate so I can move forward with a new perspective. That’s where I’m at.

JTP: I love that—looking for pockets of energy that are there, but haven’t quite been found.

PO: That in addition to how do we tell the truth in a country of lies? What does that mean? Everything’s been blurry to the point that you begin to doubt. That’s where we are.

JTP: Definitely. And what does your work look like right now?

PO: I am working on a couple of ideas. My production is very, very, very small. I don’t produce tons of work. I only produce work that I feel is urgent and is important. So I’m working on a whole bunch of ideas for possible pieces. Of all those ideas, one will emerge and come out. I’m working with that and also teaching. I’m trying to perfect the transformation of my methodology into a philosophical pedagogy. I’m trying to figure that out without losing touch with my creative self and my sense of curiosity.

JTP: When you say philosophical, do you mean putting together a formal pedagogy? Or more in a spiritual way?

PO: Well, both. I have been teaching at Tyler over the years and I feel that I always want to be able to center myself in my pedagogy in the way that I center myself in my artistic practice.

Pepón Osorio, Scene of the Crime… (whose crime?), 1993. Photo: Frank Gimpaya

I’m looking at what I’m really good at and that which I know most, which is my methodology of getting my work done, my practice. How do I transform that into a pedagogy of philosophy? That I can go around and teach something that I feel has this philosophy at the center of the work, similar to my artistic practice. Those are the things that I’ve been doing. A lot of looking in retrospect. Really looking in retrospect at the system.

JTP: That’s great. I’ve enjoyed being at CAA because I’ve been thinking more about history. It’s always there for you to learn from. The more you dig into it, the more you learn about the moment you’re in.

PO: Exactly.

JTP: What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in your time at Tyler as part of the faculty?

PO: The changes that I’m seeing at Tyler are new faculty members are coming in with a preoccupation that seems to be different from the history Tyler was built on. I’m looking at faculty members who are much more interested and preoccupied with things other than the object; where new faculty members are coming in with a clear understanding of what the true intention of becoming an artist is.

So I’m seeing that. I’m seeing transformations. We obviously have a new dean who is also looking at ways of transforming the past into a bright and hopeful future. Which is basically what I think this whole nation should be looking at.

JTP: I’m with you. Feels a little blurry, as you said, right now.

PO: Exactly. I think that the new blood and new faculty members that are coming to Tyler are interested in redefining a lot of concepts. I see that a lot in the world. I see that a lot with new generations of people coming up who are very interested in: “Let’s redefine this thing, because the system as it is simply doesn’t work.”

JTP: Would you say that’s your favorite part of being on the faculty at the moment?

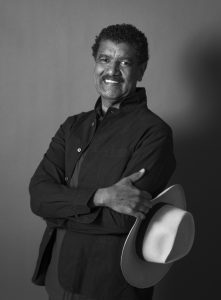

Pepón Osorio

PO: Yes. Also because I always feel that I found a niche in this. As an artist, dealing with the social, the political, the truth, and interdisciplinary work that creates very complex, chaotic environments—all that stuff seems to be so unacademic. I came in and I just felt like, “What in the world? What is my place in all this?” Little by little, by joining a new faculty and redefining, it’s making perfect sense. I’m finding myself more and more comfortable. That there are people around me that are supportive, that understand my trajectory and understand how I got to where I am now, whatever that place is.

It’s wonderful and I think to me that is a highlight. It’s finding a space in academia that feels comfortable and that I can bring the complexity of who I am into it, without necessarily having to be only one person.

JTP: I think that’s beautifully put. Everyone brings their own experiences. No one wants to be part of a monolithic institution that doesn’t let people be themselves …well, ok, some people do. But it’s interesting to me there’s so much more openness for that than I thought there might be, coming to a traditional academic membership organization like CAA, for instance.

PO: Basically, for me, it feels that this is not in demand. I am not filling up a demand of what all the people want to see. This is who I am. In relationship to the earlier question, I just feel like I was able to figure out a way to become myself in a world where people have demands of, “Oh you should be a professor.” Everybody thinks that you should be a [certain type of] professor. No. You just can’t be anybody else but who you are. It just so happened that being a professor is part of that.

We are looking at being an artist from a three-dimensional reality and in a more inter-dimensional way—that being an artist and professor is a very complex human being. I love that. I’d love to embrace that and not hide it from anyone. As a professor, I come in with all my imperfections as well. It’s not like I’m trying to correct them, I’m just going to do a balancing act with all this. That’s me, anyway.

JTP: If there was one thing that you would recommend to students or artists that they should be reading that they aren’t, what would you recommend?

PO: I’m not sure, but a student did ask me the other day if I have a recommendation of what he should be reading and what came out, which is really interesting, was feminist literature. Just listen to that stuff, read it, and understand what it means so then you can place yourself, as a male, in a place of understanding. That’s all.

JTP: I love it—you say, “Yes, I have an answer. Feminist literature.” Done.

Detail, En la barbería no se llora (No crying allowed in the barbershop),

1994. Photo: Frank Gimpaya

PO: I think that women should be reading it, but I think that men should be getting into it and reading and understanding where it comes from. I think that people, mostly men, will probably begin to empathize with the reality and the system, the fact that it’s not supportive of women.

JTP: I’m curious if you’ve attended CAA conferences in the past? What did you think?

PO: I have participated in the past. I have been in a couple of them.

JTP: It’s my first experience with the conference. It’s enormous.

PO: Yes, it always surprises me how the college system is much bigger than what I always think of it. I just wish that there were much younger people coming in to turn this thing upside down.

JTP: I agree. We’re trying to think of different ways to get closer to that. This year I know that we’re doing outreach to high schools in LA for all the free events. How amazing would it be to have a whole bunch of juniors and seniors in high school from a local public LA high school show up at the LA convention center alongside established, older academics? Just everybody.

PO: So both of them can see each other. Both of them can see each other and it’s like, “Okay, this is what’s coming up,” and the younger will say, “Oh, this is what it’s been.”

Find a happy medium somewhere in there. It’s just too much of the extremes. That’s my reaction. Too much of the extremes.

JTP: I agree. It reminds me of reForm, even just in terms of space—basically allowing people to feel comfortable. I just loved that the Bobcats (high school students who collaborated on the project with Osorio) walked through the main space of Tyler to get down to their classroom. It made Tyler theirs, in a way.

PO: A lot of people asked me, “Why aren’t you doing this piece in their neighborhood?” It was because the chances for the students to come into a college and to occupy space in a college environment were one in a million. I just thought if we can open up a space for them to occupy a classroom, open up a space for them to understand and to begin to look at the social architecture of a university, that’s more than enough for me.

I think that’s basically what I’m referring to when I’m talking about the CAA conference. If we can only suggest and show up a little bit more, that it’s much bigger than that, and that there’s a world out there both ways, that’s it. That’s what needs to happen. So people can come and begin to think differently. That was exactly what happened with the Bobcats. I said, “I’m just doing this at the institution because there are multiple functions in which the institution can work. This is one of them.” We think about institutions as the only place for education. Education is much bigger than that.

JTP: I agree, and I think that gets us closer to the truth you were talking about earlier. It opens up many more opportunities.

PO: Yes. It unties that sense of curiosity in all the kids’ minds.

reForm, 2014-2016, installation at Tyler School of Art classroom. Photo: Constance Mensh

JTP: Do you think artists can change the world?

PO: I think artists have changed the world. I think that the changes that I have seen in this country are not by artists alone, but I think that they have. When you’re talking about artists, I think you’re mentioning just these single artists changing the world, and I don’t think that that has happened. But I don’t think that that cannot happen.

I’m saying yes, because in the changes that I’ve seen in the world, there has always been an artist behind that. I do agree, but I don’t think that an artist alone can do it.

To break it down, I think that creativity has always been at the center of world’s change. Artists have always been on the periphery of it. Sometimes at the center of those changes.

JTP: Great, thank you. Lastly, you touched on this a bit, but what gives you hope for the future?

PO: Change.

JTP: Pepón, I’m right there with you. The possibility that it won’t be how it is right now.

PO: Exactly. That’s all. I just hope for change.

CAA’s Annual Conference Convocation, including the presentation of the Awards for Distinction, will occur February 21, 6:00-7:30 PM and will be livestreamed.

Call for CAA 2018 Los Angeles MFA Exhibition “Sustainability and Public Good”

posted by CAA — September 21, 2017

Call for CAA 2018 Los Angeles MFA Exhibition “Sustainability and Public Good”

Exhibition Dates: January 25 – February 24, 2018

The CAA’s Regional MFA Exhibition in Los Angeles invites artists from MFA programs in California. Participating artists must be current MFA students with current CAA memberships. Student work will be selected by a committee comprised by a number of eminent Los Angeles gallery directors. This exhibit is concurrent with the 106th CAA Annual Conference in Los Angeles, CA.

While exhibitions may feature artwork in any medium, 2-D, 3-D or wall-mounted artwork; the works should be suitable for a gallery display. Please be informed that all exhibiting work will be insured. However, participants are responsible for shipping and transportation costs, both to and from the Cal State LA Fine Arts Gallery.

A closing reception for the artists, their professors, and the CAA’s conference attendees will take place on Friday evening, February 23, 4:00–8:00 PM. The exhibit is Free and open to the public.

Submission Guidelines

All Electronic Exhibition Proposals should include the artist’s statement, vitae, and a maximum of three high-resolution .jpg images (one work per artist or one work per group of collaborated productions will be selected for display. Please send your electronic exhibition proposals no later than 5pm on October 10th of 2017 via Email (mcho@calstatela.edu). Please indicate your name and CAA membership number on the subject line, example: “John Doe, CAA Membership Number”. If you may include all information in one PDF file, which best facilitates the reviewers. Please note that all images must include caption, title when applicable, medium/media, year made, and insurance value.

Dr. Mika Cho, Professor of Art, Director of Cal State LA Fine Arts Gallery

California State University, Los Angeles

Email: mcho@calstatela.edu

Tel: 323-343-4022/4040

Timeline: Exhibitions will occur between January 25, 2018 and February 24, 2018.

Submission Due: October 10, 2017

Please submit as per instructions above NOT to the College Art Association, New York office.

Notification: Artists will be notified via email by October 25, 2017

Work delivery: January 15 to January 19, 2018, Work will not be accepted after 5pm on the 19th of January

Installation: January 22 to January 24, 2018

De-installation: February 25 to February 27, 2018

***The Cal State LA Fine Arts Gallery is located in the Fine Arts Building at California State University, Los Angeles (5151 State University Drive, Los Angeles CA 90032), a few miles east of Downtown LA. The regular gallery hours are Monday through Friday 12:00-5:00 PM. The Fine Arts Gallery at Cal State LA is to serve the needs of an urban and diverse university community and to provide a forum for the investigation of a wide range of visual cultures. The Fine Arts Gallery presents cultural exhibits, professional artists, Cal State LA faculty, and graduate and undergraduate students year around under the

supervision of the Director, Dr. Mika Cho.

Artist Mimi Gross in Conversation with Hunter O’Hanian

posted by CAA — September 14, 2017

Artist Mimi Gross is the daughter of sculptor Chaim Gross and serves as the president of the Renee & Chaim Gross Foundation, based in Greenwich Village in New York City. Mimi Gross’s work has been part of many international exhibitions, including work at the Salander O’ Reilly Galleries, and the Ruth Siegel Gallery, New York City, the Inax Gallery, in Ginza, Tokyo, and Galerie Lara Vincey, in Paris. She has also shown work at the Municipal Art Society and at the Port Authority Bus Terminal. Her anatomically-themed art-work is on permanent display, courtesy the New York City Parks Department, at the Robert Venable Park in East New York.

The Renee & Chaim Gross Foundation houses an extensive collection of over 10,000 objects that includes Gross’s sculptures, drawings, and prints; a photographic archive; and Gross’s large personal collection of African, Oceanic, Pre-Columbian, American, and European art that remains installed in the townhouse as Gross had it during his lifetime. The Foundation is open to the public and tours are available through the website.

—Mimi Gross

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Hi. I’m Hunter O’Hanian. I’m the director of the College Art Association, and I’m very fortunate to be here today with Mimi Gross. Hello, Mimi. | |

| Mimi Gross: | Hi. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Thank you. | |

| Mimi Gross: | Glad to be together. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Thank you, yes. And it’s been nice to catch up about our time in Provincetown together. | |

| Mimi Gross: | Yeah. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | We have spent a lot of time there. | |

| Mimi Gross: | We do. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | But thank you very much for inviting us into the home of the Foundation, the foundation that was set up by your parents. And it’s really amazing, and we’re going to get to talk about lots of that stuff. | |

| Mimi Gross: | Right. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | But so our viewers actually see what’s going on, can we talk a little bit about the pieces of artwork over my head here? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Oh, of course. Very happily. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Yep. | |

| Mimi Gross: | So we start, this is by Mane-Katz. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Yep. | |

| Mimi Gross: | Who was a great, shall we say, French-Israeli-American painter, and it’s a Purim Boy. It’s a Milton Avery above it, Woman in Blue. Next to it, this is by Orozco, Mexican master. This is by Louise Nevelson when she was very young, and she was my father’s student. This is by Marsden Hartley. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | You said I could take this one home, right? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Well, you might try. We might catch you at the door. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | I saw you had good security here, so … | |

| Mimi Gross: | Yeah, we do.

Above it is Francis Crisp. He was a great painter. The two dark men, that surreal painting is by Federico Castellón, a Spanish American painter. Below it is by John Metzinger, a great friend of Leger and strangely, post-modern today. Above is by Raphael Sawyer. I don’t know how far you go, but next to it is Louis Guglielmi. He was a Great Depression painter. |

|

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Where in the house did your parents … Your dad worked, right? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Yes. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Tell us a little bit about your father’s career. | |

| Mimi Gross: | His career? | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Yeah. | |

| Mimi Gross: | He was a carver. That was his prime interest in his artwork. He came to America as a teenager at age 17 and went to the Education Alliance and studied there and then taught there. He studied with Elie Nadelman. He studied with Robert Laurent. Before that, he started as a painter and John Sloan was his teacher and saw his drawings were very dimensional and said, “Why don’t you try studying sculpture?” He took to it immediately, and that was his love … | |

| Mimi Gross: | Which continued throughout his life. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | The building that we’re in now on La Guardia Place, how long did your parents have this building? | |

| Mimi Gross: | They got it in ‘62, ‘63 when they moved in, and they were looking for a place that would be a permanent home for his work and for his collection. I grew up in Harlem at my home had all these things in it, but not this building. He always had a studio in the village. That was his territory. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Was your mom a maker as well, too? | |

| Mimi Gross: | She took care of everyone. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Did she? Good for her. She was probably one of the busiest people in the household. | |

| Mimi Gross: | She was very busy. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | You said you grew up in Harlem. Tell us a little bit about your education. | |

| Mimi Gross: | School of hard knocks. I went to high school music and art and then to Bard College. After two years I went to Europe and spent several years there. That was a major part of my education. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | What was that like growing up with an artist family? Who was coming around the house in those days? Who were your parents chumming around with? | |

| Mimi Gross: | My other father was Raphael Sawyer, and I posed for him a lot and got to know him very close. Milton Avery who also came to Provincetown and knew him in the summertime. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Right. You spent summers in Provincetown? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Since I was a little girl. | |

| Mimi Gross: | And still do. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | One of the reasons why we’re here is to talk about this Spring/Summer issue of the Art Journal, which really talks about artist legacies. You have a great piece in here on page 129, which really talks about the legacy of your parents and the Gross Foundation here, and so we’ll get into some of that, but what brought your family to Provincetown? | |

| Mimi Gross: | That’s actually a sensitive subject. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Oh. | |

| Mimi Gross: | First of all, it’s a artist colony as it’s known, they had spent several summers in Rockport on Cape Ann, which also is an artist colony. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | In Massachusetts? | |

| Mimi Gross: | In Massachusetts came that period before World War II started. World War II started and anti-Semitism was very wide-spread in New England. They heard that Provincetown was liberal, which it still is, or it’s maybe not as liberal as it once was. It was a Portuguese fishing village. It was unlike general New England, so they migrated there and loved it, stayed. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Your family ended up having a house there, and that’s how you ended up being able to go every summer? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Yep. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | You were trained as an artist yourself. There’s the lovely picture of you at the beach making a painting. Tell us a little bit about your artistic career. | |

| Mimi Gross: | My career itself? | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Mm-hmm (affirmative). | |

| Mimi Gross: | It’s what we’d call the bumpy road to somewhere. I’ve had several, you could call it emerging moments, where there was a notoriety of a sort, but I’ve been working since I’m a teenager very seriously as a painter. I’ve worked with many materials, mainly to paint them. That’s been my quest in life. I’m a figurative painter, but I’ve tried many different things. I’ve done a lot of costumes and sets for dance, in particular, Douglas Dunn. When I was married, we did a lot of movies with animation. That was a lot of artwork as well. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | You were married- | |

| Mimi Gross: | My career in terms of gallery life, I showed with several different galleries which closed, so right now I don’t have any gallery, though I had two shows very recently, this spring. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Right, and you were married to Red Grooms, as you said? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Yes. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Yes, and you had several children with Red? | |

| Mimi Gross: | One daughter, Saskia. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Yeah, wonderful. Great. | |

| Mimi Gross: | And two granddaughters. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | You and Red made films together? | |

| Mimi Gross: | We did. Many films. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | You collaborated on other projects, too? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Yes, we collaborated on very large, walk-through installations that he called pictosculptoramas. They were gigantically room-sized. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Right. Your parents over the year…. Certainly your father was incredibly prolific, and you have been very prolific as an artist. Through your relationships you’ve gathered a lot of work, traded it with other artists. I read that there was possibly 10,000 objects that you have at this point. | |

| Mimi Gross: | In this house. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | In this house. | |

| Mimi Gross: | I don’t have that many objects. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | No, no, but I mean in- | |

| Mimi Gross: | But my parents were, they were serious collectors. The African art collection is, in itself, multiple objects. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | The question always comes up then about, for people who are art makers or collectors, what happens to that work? And what is- | |

| Mimi Gross: | Good luck. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Yeah. Good luck, right, an artist’s legacy going forward. What do you say about that? | |

| Mimi Gross: | When I was asked to write this article, at first I said, “Oh, sure,” thinking that it was not a difficult answer, knowing that we made this foundation, but when I really thought about it, I realized that my own life and work was something that I had not particularly addressed, as well as the works I did with Red when we collaborated and we both own. It was complicated and difficult to actually freely write it.

I would say that in terms of how an artist who has objects, how they deal with it, it has a lot to do with their own reputation, their own finances and their own ambitions, and their support. All of these things make it work or not work. My father would say things like, “Oh, I have a daughter that will take care of it,” so I think my granddaughters, maybe they’ll help. There’s no way of knowing, but the finances are gigantic issue, and even here where we have all of this work and a fantastic building, it still is the main issue is fundraising. |

|

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Right. Again, we’re here at La Guardia Place in The Village in New York. People can actually come and see the work. | |

| Mimi Gross: | Oh, yes. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | They can contact the foundation to make an appointment and have a docent led tour. | |

| Mimi Gross: | It’s open to the public. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Which is great.

When I was asked to write this article, at first I said, “Oh, sure,” thinking that it was not a difficult answer, knowing that we made this foundation, but when I really thought about it, I realized that my own life and work was something that I had not particularly addressed…. It was complicated and difficult to actually freely write it.

—Mimi Gross |

|

| Mimi Gross: | We were well-situated here. I say “we” because I helped my parents get this together. Well-situated when Soho was extremely active as an art center, so people were visiting galleries, and then they knew my father or they heard about him and they would drop by and visit. That evolved that way, but today it’s not an art center, though there are several pockets of places here. There is a consortium with the various places that are still in the neighborhood, but because it’s still easily located near Washington Square and near the subways, people come by.

We have about 5,000 people come here a year. Then we’ve been part of Open House New York and in one weekend have over 1,000 people come. We’re part of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, so all of that’s part of this particular foundation. |

|

| Hunter O’Hanian: | The foundation was set up by your father. | |

| Mimi Gross: | No, by his friends. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | By his friends? So- | |

| Mimi Gross: | They did it as a birthday present at one point. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | While he was still alive they set up the foundation? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Mm-hmm (affirmative). | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Did he set the original mission for the foundation when they set it up or … | |

| Mimi Gross: | No, he actually … He was modest. It was done around him. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Yeah. Yeah, so it was done around, it was his friends, basically, who got together who decided that … | |

| Mimi Gross: | Yeah. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | I think I read that he thought, oh, maybe it might last 10 years or so, or 20 years. | |

| Mimi Gross: | He went like this. Yeah.

We tried to make a gift to, of course, NYU, since they’re neighbors. They own the building next door, for example. We went to City College and Pace College, to the new school, to Yale University. There was quite a few genuine almosts, but he offered the building with everything in it, but without the millions of dollars that are needed to keep it going, and so in the end a friend said, “Why don’t you just make your own place?” In Europe, it’s very, very common for a home and a studio to be that artist’s resting place for people to visit, so it was based on that. |

|

| Hunter O’Hanian: | We don’t see so much of that in the United States. | |

| Mimi Gross: | Famously, the Delacriox home and studio that people come to visit in Paris. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Sure, sure. Some of the conversations that your family had with the institutions in the area, they were hopeful in the beginning, but then it didn’t resolve? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Exactly. It took a lot of time. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | What do you envision will happen to all this work 50 years or 100 years from now? | |

| Mimi Gross: | I don’t. It’s way beyond my envisioning. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Really? Yeah. | |

| Mimi Gross: | I do believe some of it will remain. It’s just there’s no way of knowing what will happen to any of us in 50 or 100 years. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Of course, of course. | |

| Mimi Gross: | It’s a very big question mark. First of all, we might be underwater. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | In this part of New York. | |

| Mimi Gross: | I hope not. Our future director, hopefully, will be a fundraising person. Hopefully, that will … He does believe in the sustainability. He does believe that we will continue, and with that in mind, hopefully, we’ll have classes, more visitation, and more of a educational outreach. I think that will help sustain here. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | If you were to give advice, now that you’ve spent so much time doing this, but if you were to give advice to artists in their 40’s, 50’s, or 60’s who are thinking about their legacy and what will happen to all that work, what kind of advice would you give them? | |

| Mimi Gross: | I think again it has a lot to do with their reputation in public, their finances, their affiliation with a professional gallery or whatever that way. When you think about it, there is an amazing consortium now of artists’ foundations, artist/family foundations. That is a source of continuity. It’s great. Charles Duncan from the Archives of American Art is the head of it. There has been several meetings. The Aspen Papers have been published on bylaws for a foundation. It’s not a totally easy thing to do, but it’s also not impossible. If you have the work and you want to preserve it, it’s one way to do that. Another is to make gifts to the many, many university museums, small museums all over the country that are eager to increase their collections. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Do you work to try to place some of your father’s work in those museums and] collections? | |

| Mimi Gross: | I’ve started to. Yes. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Yeah. Do you find that to be valuable? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Beyond valuable. There’s now a sculpture that I gave to the Metropolitan Museum that’s on display … | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Fabulous. | |

| Mimi Gross: | Between the Edward Hopper and Charles Demieux. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Oh, my god. How wonderful is that? | |

| Mimi Gross: | Yeah, it was thrilling. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Also, we were talking earlier, you have three staff people. | |

| Mimi Gross: | Correct. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Or you will with your new director here, but just the idea of keeping track of all of this work and where it is, particularly with a prolific artist like your father, it must be a mind-boggling task. | |

| Mimi Gross: | Fortunately, we’ve had really great interns, really great work. Then we’re also, we’re pioneers if you compare us to other foundations that are much younger. Basically, everything here has been inventoried, although new things are always being found. Last week my granddaughter found a whole bunch of new things that were not discovered before. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | Wow. You would have thought by this time you would have opened up all the drawers in the … | |

| Mimi Gross: | Yeah, you’d think. | |

| Hunter O’Hanian: | That’s great. I hope we get to see you at a college art association conference. Maybe we can even bring some people who come to the conference here. | |

| Mimi Gross: | I would really urge you to bring guests here and be part of your organization. |

ARTexchange Submissions for CAA 2018 – Deadline Extended!

posted by CAA — September 05, 2017

The Services to Artists Committee invites artist members to participate in ARTexchange, CAA’s pop-up exhibition and annual meet-up for artists and curators. This social event provides an opportunity for artists to share their work and build affinities with other artists, historians, curators, and cultural producers. ARTexchange will take place at the 106th Annual Conference in Los Angeles on Friday evening, February 23, 2018, from 5:30 to 7:30 PM.

Each artist is given the space on, above, and beneath a six-foot table to exhibit their work: prints, paintings, drawings, photographs, sculptures, and small installations; performance, process-based, interactive, and participatory works are especially encouraged. CAA encourages creative use of the space and in the past this set up has sparked many unique displays. Please note that artwork cannot be hung on walls, and it is not possible to run power cords from laptops or other electronic devices to outlets.

To participate as an exhibiting artist in 2018, email caaprograms@collegeart.org, with “ARTexchange” and your last name in the subject line, by (deadline extended!) December 15, 2017, with the following information: (1) a short description of what you will exhibit and how you will use the six-foot table space (provide details regarding performance, sound, spoken word, or technology-based work, including laptop presentations); (2) your CAA member number (memberships must be active through February 24, 2018); and (3) your website or a link to a digital portfolio.

Because ARTexchange is a popular venue and participation is based on available space, early applicants are given preference. Participants are responsible for their work; CAA is not liable for losses or damages. Sales of work are not permitted.