CAA News Today

International News: “My World Now Is Black in Color:” Pandemic-Era Programming, Anti-Racist Activism, and Contemporary Art in Italy

posted Aug 11, 2020

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Tenley Bick, Assistant Professor of Global Contemporary Art, Department of Art History, Florida State University, and the 2019–20 Scholar in Residence at Magazzino Italian Art Foundation, New York. A related essay, “Ghosts for the Present: Countercultural Aesthetics and Postcoloniality for Contemporary Italy,” will be included in an edited volume forthcoming from Lexington Books.

Figure 1. “Indro Montanelli, imbrattata la statua a Milano” (Indro Montanelli, statue smeared in Milan). Corriere della Sera, June 13, 2020 (https://www.corriere.it/cronache/20_giugno_13/indro-montanelli-statua-imbrattata-81a5c120-adad-11ea-84a7-c6d5b5b928b0.shtml). Photo: AP

June 13, Milan. The 2006 monument to Italian journalist Indro Montanelli was found covered in red paint and tagged “razzista, stupratore”: racist, rapist. The intervention targeted the statue of Montanelli and the journalist’s past as a colonial soldier in East Africa. In 1935, Montanelli bought a twelve-year-old Eritrean girl, Destà, to serve as his wife under the practice of madamismo. Montanelli never apologized. The intervention ignited public debate in Italy on racism and public monuments, bringing the country popularly known for apathy toward its colonial and fascist histories, pervasive associated monuments and street names into renewed transatlantic debates on these topics. Four days prior, Italian-Somali writer Igiaba Scego, writing on anti-Black racism, Black Lives Matter, and monument debates in the United States and Europe in the Italian weekly Internazionale, made a call for Italy to confront the “uncomfortable traces of our past.” Citing an earlier intervention at the Montanelli monument in 2019, Scego noted the absent memorialization of Destà: “It would be nice if someone, whether a street artist or a municipality, dedicated a statue, a drawing, a memory to that distant child” (trans. Bick). Street artists and activists responded (Figs. 2–3). Cities did not. The Montanelli monument was cleaned and, by mayoral decision, remains in place.

Figure 2. In Milan, Italian street artist Ozmo’s mural depicts a fictional monument to Destà, the Eritrean child “bride” of Indro Montanelli, when the famous journalist was a colonial soldier. Working specifically in response to Igiaba Scego’s call, the artist used a photo of a contemporary Eritrean girl of approximately the same age as Destà upon her “marriage,” to stand defiantly in place of Montanelli on the base of his monument, relabeled in memory to “Montanelli’s child bride” (IG @ozmone, June 15). The mural was vandalized within two days. Inkjet on blueback paper, measurements to site (dimensioni ambientali). Photo by Gianfranco Candida, @wallsofmilano. Courtesy of Ozmo.

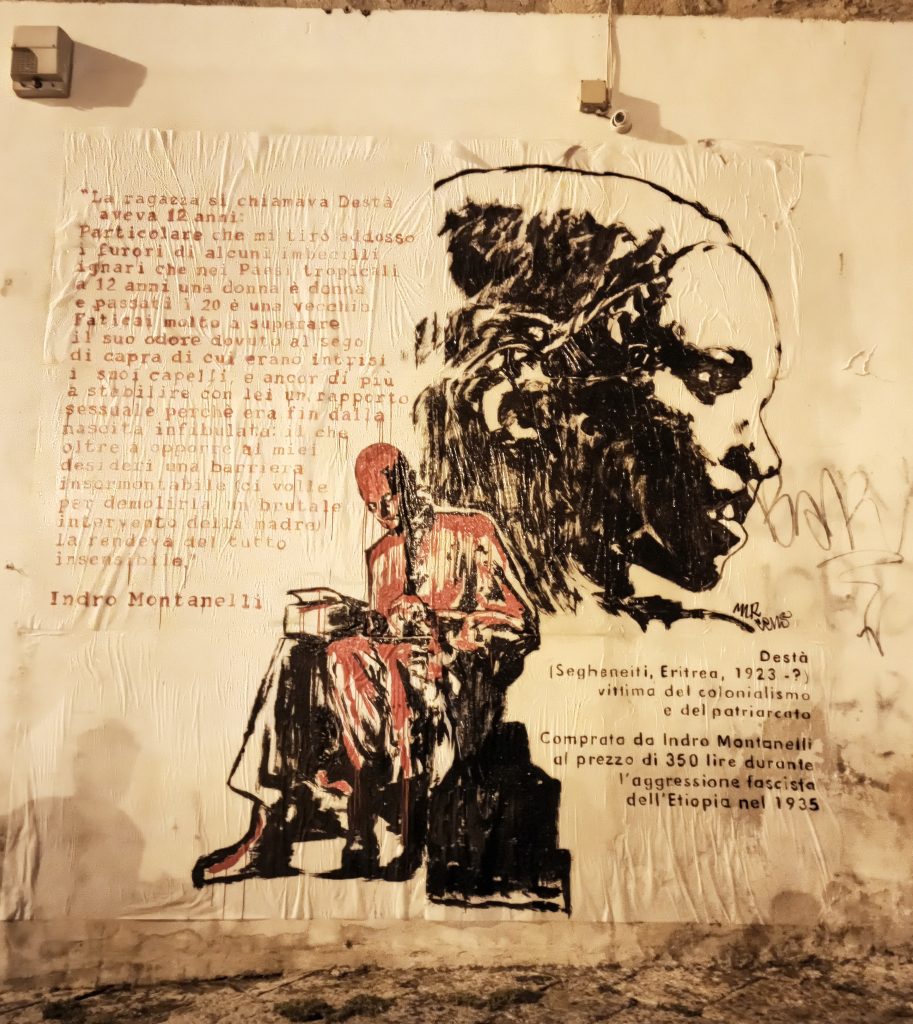

Figure 3. In Palermo, artists Mr. Cens, Betty Macaluso, and Ulrike conceived the mural depicting the vandalized monument to Montanelli and a portrait of Destà. Mr. Cens executed the large public mural. Acrylic on tissue paper, 9.8 x 9.8 ft. (3 x 3 m). Palermo, June 16, 2020. Courtesy of Mr. Cens. The mural builds upon a 2018 work by Wu Ming 2 (Giovanni Cattabriga) and Palermo-based artist collective Fare Ala (Luca Cinquemani, Andrea Di Gangi, Roberto Romano), Viva Menilicchi!, which temporarily renamed via Montanelli “via Destà.”

One of the first hotspots in the COVID-19 pandemic, Italy was then emerging from a three-month lockdown. During that time, Italian museums (public and private) became leaders in innovative arts programming for a pandemic-era world. The Museo Madre launched an #iorestoacasa “call to action” campaign, publishing artists’ responses to the pandemic online; the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna invited and posted videos about its permanent collection; the Fondazione Prada produced podcasts and alternative exhibition encounters through its #innerviews and #outerviews programs, using social media as a “laboratory” for “new formats and codes” (@FondazionePrada, Mar. 18). This innovation has since extended to safety technology. Florence’s Museo dell’Opera del Duomo introduced wearable sensors to ensure social distancing—technology subsequently implemented by institutions of Italian art outside of Italy. Magazzino Italian Art Foundation (New York) is the first museum in the United States to use the technology, reopening with Homemade (cur. Vittorio Calabrese with Chiara Mannarino), an exhibition of work made during the pandemic by New-York-based Italian artists.

While the Montanelli debate coincided with a moment of reckoning for institutions in the United States and Western Europe, the overwhelming majority of art museums in Italy have not announced such programming, policy changes, or statements of solidarity. This inattention is not due to a lack of anti-racist social justice activism in Italy (Black Lives Matter Roma, Neri Italiani, the Stati Popolari movement, among others), nor is it due to an absence of Black Italians in Italian popular culture, especially in literature (Scego), cinema (Fred Kuwornu, Amin Nour), and music (Ghali).

A few exceptions demonstrate the potential for institutionally supported, sustained, collaborative programs to counter anti-Black racism in Italy. The Uffizi has partnered with Black Lives Matter Florence on a series of virtual programs to address “the presence of black culture in European art, told through the works of the Gallerie degli Uffizi” (https://www.uffizi.it/video-storie/black-presence). Organized by Justin Randolph Thompson, co-founder and director of Black History Month Florence (BHMF), in collaboration and partnership with the Uffizi as part of their On Being Present program, the eight-week series entitled “Black Presence” debuted July 4th with Thompson’s video discussion of a Piero di Cosimo work and continues with concerts and video tours on representations of Black Africans in Renaissance art. MAXXI, one of Italy’s major contemporary museums, launched a short-lived social media initiative: #MAXXIforblacklivesmatter. The campaign “aims in raising awareness and consciousness of the @blklivesmatter movement through art” (@museomaxxi). With eighteen tagged Instagram posts (most recently dated June 17), the museum posted images of BLM protests in Italy and works by African and African diaspora artists Robin Rhode, John Akomfrah, and Yinka Shonibare from MAXXI’s 2018–19 exhibitions. The initiative was highlighted on June 12 by Italian-Haitian-Ghanaian cultural curator and Griot founder Johanne Affricot in an essay for Artribune as a “necessary” if late action amidst the generally delayed response from arts and culture in Italy to BLM in comparison to the global context (“Black Lives Matter ma non in Italia. Il ritardo dell’arte e della cultura nel paese,” June 12). Program information is notably no longer available on MAXXI’s bio.

Beyond these varied efforts, Black artists have been included in major museum and gallery exhibitions, and Black curators have curated exhibitions at prominent museums, but these figures are almost always non-Italian artists and art workers. While Italy is becoming increasingly multi-ethnic (and multi-racial), the country does not track ethno-racial statistics (Reynolds 2018, BBC; Ambrosetti and Cela 2015). Instead, citizenship and place of birth serve as “proxies” for race and ethnicity (Ambrosetti and Cela 2015). This is one of many reasons—from racial laws under fascism to renewed racism in response to cross-Mediterranean migration—why Blackness in Italy is most associated with foreign identity (with populations of African migrants, immigrants, and residents) rather than with Italian identity as well.

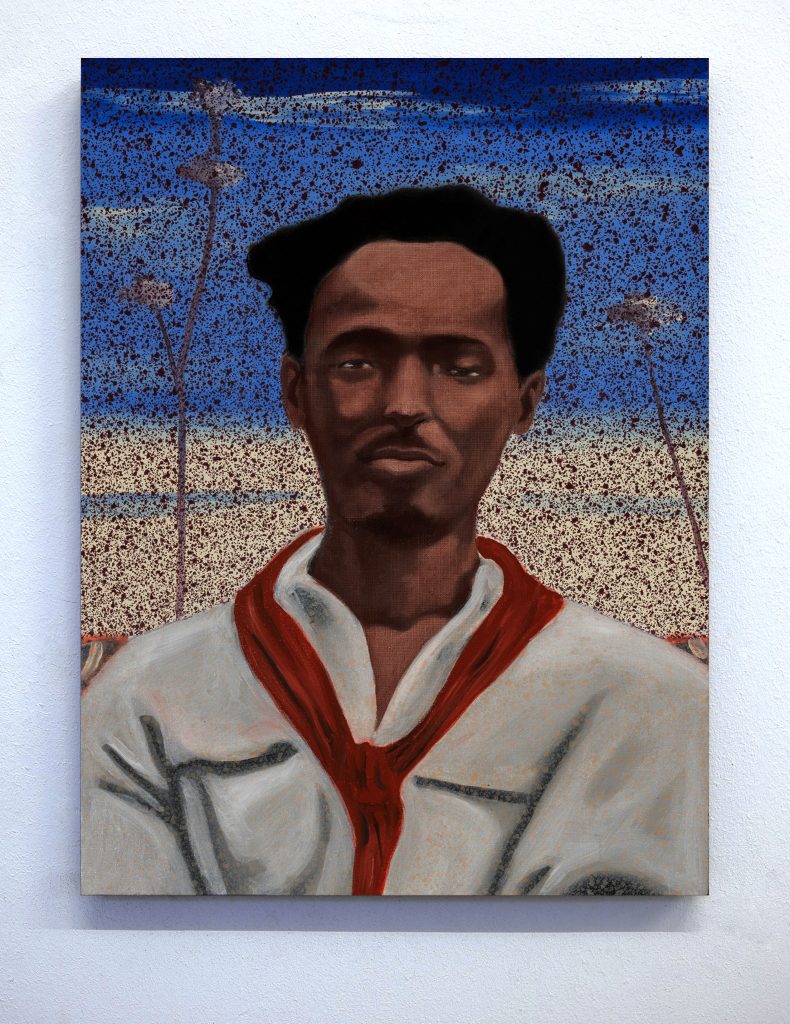

Two Afro-Italian artists—Jem Perucchini (b. 1995) and Luigi Christopher Veggetti Kanku (b. 1979), both based in Milan—are making inroads that might change that. Perucchini made a series of portraits of Black Italians in history for Vogue Italia during Black History Month (see Jordan Anderson, Mar. 12, 2020) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Jem Perucchini’s Alessandro Sinigaglia (2020) depicts a little-known Black, Jewish Italian member of Italy’s anti-fascist resistance during World War II. Oil on linen, 15.75 x 12 in. (40 x 30 cm). Courtesy of Jem Perucchini.

Harper’sBazaarTV followed with a “visual interview” in mid-July. When asked “What colour is your world, these days?” the Ethiopian-Italian artist responded: “Certainly my world now is black in color. I think it is the color that is most suited to represent the situation that the whole world is experiencing, in terms of sanitary, economic, social problems” (interview by Laura Taccari, trans. Bick). At the end of lockdown, Perucchini had completed a large painting of the Stele of Axum: the ancient obelisk that Italy returned to Ethiopia in 2005, nearly seventy years after stealing it as war spoils (Zoom interview with Bick, Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Jem Perucchini, Axum, 2020. Oil on linen, 55 x 43 in. (140 x 110 cm). Courtesy of Jem Perucchini. Completed during the lockdown, Perucchini’s Axum depicts the fourth-century stele that was taken as war spoils during Italy’s second colonial invasion of Ethiopia. The stele remained on display in Rome for nearly seventy years.

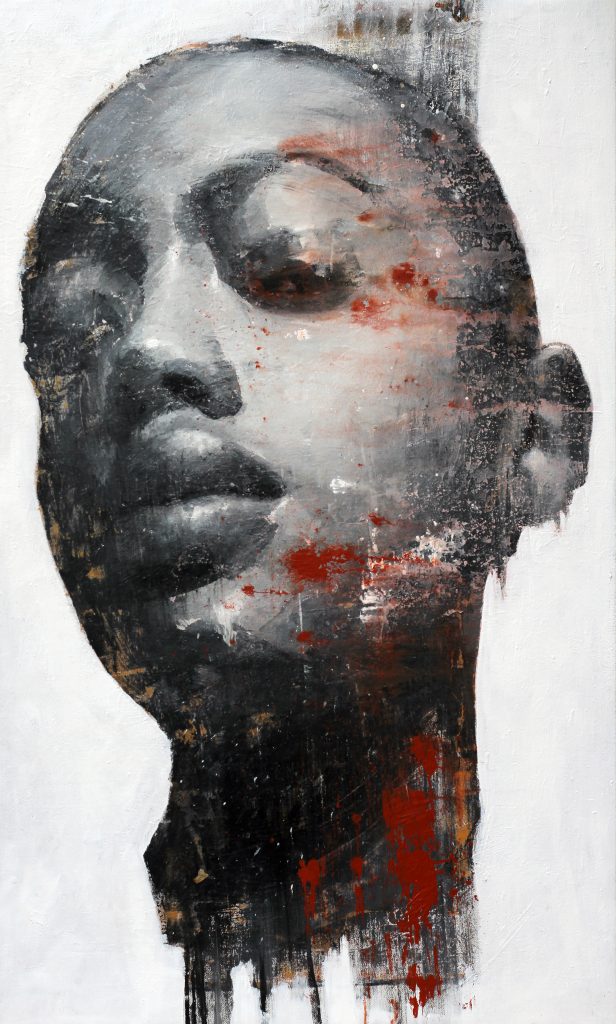

Veggetti Kanku (represented by Galleria Rubin, Milan) has confronted the institutional and cultural marginalization of Black people in Italy directly. In late June, the Congolese-Italian artist held a soft opening of a new exhibition space in Milan’s center for Afro-Italian artists (Zoom interview with Bick, Jun. 29). Entitled The Office, the evenings-and-weekends-only arts space is a legal office during regular business hours. Veggetti Kanku’s monumental portraits of Black women (Fig. 6), intended to bring Black figures into (white) Italian bourgeois homes (Griot, Mar. 25; Zoom interview with Bick), hang in the space, to be inaugurated this fall with his solo show SOTTOPELLE: “A show dedicated to black women, inclusive of social status, a show that destabilizes and puts up for discussion the canons of strictly Western beauty in an ever-increasing multi-ethnic Italian reality” (Veggetti Kanku, email correspondence with the author, July 16, trans. Bick).

Figure 6. Luigi Christopher Veggetti Kanku, Untitled, 2020. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 65 x 39 in. (165 x 100 cm). Veggetti Kanku’s monumental portraits of Black women will be exhibited in his solo show, SOTTOPELLE (UNDERSKIN) at his new space for Afro-Italian artists, The Office, located in the center of Milan.

The museum complex now perhaps most directly engaged with Italy’s colonial history, the Museo delle Civiltà (home to Italy’s national ethnographic museum and partial repository of Italy’s colonial collection, formerly at the Museo Coloniale di Roma and various iterations that followed), has announced plans for a new museum (in development since 2017) dedicated to Italian colonialism in Africa (including postcolonial periods and an engagement with contemporary art): the Museo Italo-Africano Ilaria Alpi, to open in 2023. (See Scego, and Giulia Grechi and Viviana Gravano’s interview with colonial collections’ curator and cultural anthropologist Rosa Anna Di Lella in Roots–Routes). As Italy begins to address the presentness of its colonial past, the absence of Black Italian artists in Italy’s museums and galleries persists. What might a Perucchini or Veggetti Kanku exhibition look like at MAXXI or the Galleria Nazionale? What might happen if the innovation of Italian arts programming and centrality of the arts to Italian identity made space for the multi-ethnicity of Italy today? It remains to be seen if and how the country’s art museums and galleries—leaders in arts programming in many ways—will address racial inequity in their own collections.