CAA News Today

“Warriors and Volunteers: A Review of George W. Bush, Portraits of Courage” on Art Journal Open

posted Jul 02, 2018

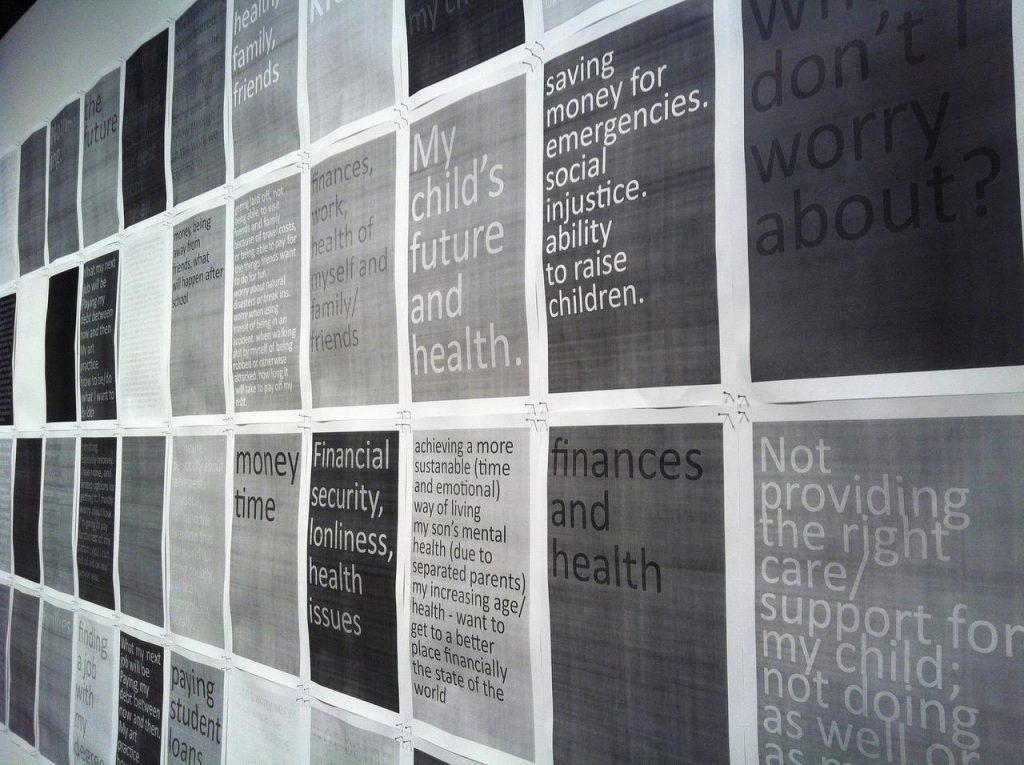

Installation images by Melissa Warak of Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors.

A new essay by Melissa Warak, “Warriors and Volunteers: A Review of George W. Bush, Portraits of Courage,” looks carefully and critically at a 2017 exhibition of paintings by former US president George W. Bush.

Warak, an art historian with close ties to veterans and active military, approaches Bush’s artistic production both technically and art-historically, but also personally and politically. Through Bush’s rendering of both visible and invisible wounds veterans sustained in the Iraq War, writes Warak, the exhibition “aims to humanize the war and highlight the president’s connection to the wounded.” Read more on Art Journal Open.

New in caa.reviews

posted Jun 29, 2018

Andrea Gyorody reviews Paik’s Virtual Archive: Time, Change, and Materiality in Media Art by Hanna B. Hölling. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Lisandra Estevez reviews Baroque Seville: Sacred Art in a Century of Crisis by Amanda Wunder. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Sabine T. Kriebel reviews Photography and Humour by Louis Kaplan. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted Jun 27, 2018

Andrea del Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child with Two Angels, c. 1468–70. Courtesy National Gallery, London, via Apollo Magazine.

‘Mounting an Exhibition about Leonardo Da Vinci Is an Act of Hubris’

Chief curator Laurence Kanter reflects on Yale University Art Gallery’s upcoming exhibition. (Apollo Magazine)

The Histories of Ten Colors Through Multiple Lenses

A new book considers color across multiple disciplines, including film and literature. (Hyperallergic)

20 Curators Taking a Cutting-Edge Approach to Art History

Artsy shares their top twenty curators who are working through a 21st-century lens. (Artsy)

How to Spot a Perfect Fake: The World’s Top Art Forgery Detective

Forgeries have got so good that Sotheby’s has brought in its own in-house expert. (The Guardian)

Backpack-Sized Archiving Kit Empowers Community Historians to Record Local Narratives

A new project from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill equips community partners with tools to start material and oral history archives. (Hyperallergic)

‘There Is So Much You Go Through Just Trying to Make It’: Amy Sherald on How She Went From Obscurity to a Museum Survey (and the White House)

The 44-year-old artist reflects on her breakout year, and the years of hard work leading up to it. (artnet News)

CAA Statement on Supreme Court Decision to Uphold Travel Ban

posted Jun 26, 2018

In light of today’s Supreme Court ruling upholding President Trump’s travel ban, we are reposting our Statement from February 2017 here in its entirety. Our values have not changed.

As we stated when we joined two amicus briefs in May 2017, speaking out against this decision is inherent to our advocacy efforts and our international reach at CAA. The travel ban impacts the international attendees of our Annual Conference, it impinges on the flow of information and discussion between colleagues, and it harms the practice of research more broadly. See the statement below.

CAA Statement on Immigration Ban, February 2017

CAA, the largest professional group for artists and art historians in the United States, strongly condemns and expresses its grave concern about the recent presidential executive order aimed at limiting the movement of members of CAA and the broader community of arts professionals who fall under the selective set of criteria for national status or ethnic affiliation.

CAA has counted international scholars and artists among its members for many years. Committed to the common purpose of understanding the visual arts in all its forms, professionals throughout the world have enriched CAA’s community by adding diverse perspectives to the study, making, and teaching of art. With funding in recent years from the Getty Foundation to support travel and programs for scholars and curators from Africa, Latin America, Russia and Eastern Europe, and Asia, the association now includes members from seventy countries. More than ten percent of our individual members are international. CAA has counted international scholars and artists among its members since the earliest years of its existence. The roots of CAA’s present-day international program stemmed from a desire to assist European refugees in the 1930s to support personal safety as well as academic and artistic freedom. During that decade, CAA had a “foreign membership” category; as art historians fled Hitler’s Europe, CAA ran a lecture bureau for refugee scholars that created speaking engagements for them at institutions throughout the United States.

The recently announced ban on travel to the United States for residents of seven predominantly Muslim countries not only goes against the inclusive, secular underpinnings of American democracy, it stifles the open access to scholarship and art upon which our work is founded. The executive order goes against our professional and scholarly commitment to diversity, the global exchange of ideas, and the respect for difference. The contribution of immigrants, foreign nationals, and people of all cultural backgrounds greatly strengthens our intellectual and creative world. Further, we believe the executive order law challenges the values at the heart of the US Constitution’s protections on speech and association as well as our national commitment to democratic process for all.

Turning our backs on refugees and closing our borders selectively stifles creative and intellectual work in addition to its very real impact on peoples’ daily lives. We call on our public officials to thwart this attempt to seemingly preserve our own safety at the expense of those who are vulnerable and who also contribute so much.

Without question, CAA welcomes all members and non-members to our upcoming Annual Conference to discuss and debate what constitutes a thriving artistic and intellectual society. Such openness is essential to our mission. We are committed through dialogue and action to help any CAA members who are affected by this policy. To this end, the association and the Board of Directors will continue to monitor and respond to policies related to this order as well as pressure for its immediate repeal.

See the original statement posted February 2017.

See CAA Amicus Brief on Trump’s Travel Ban, May 2017.

For more on CAA’s advocacy efforts, click here.

A Look at the PhD in Creativity at the University of the Arts, Philadelphia

posted Jun 26, 2018

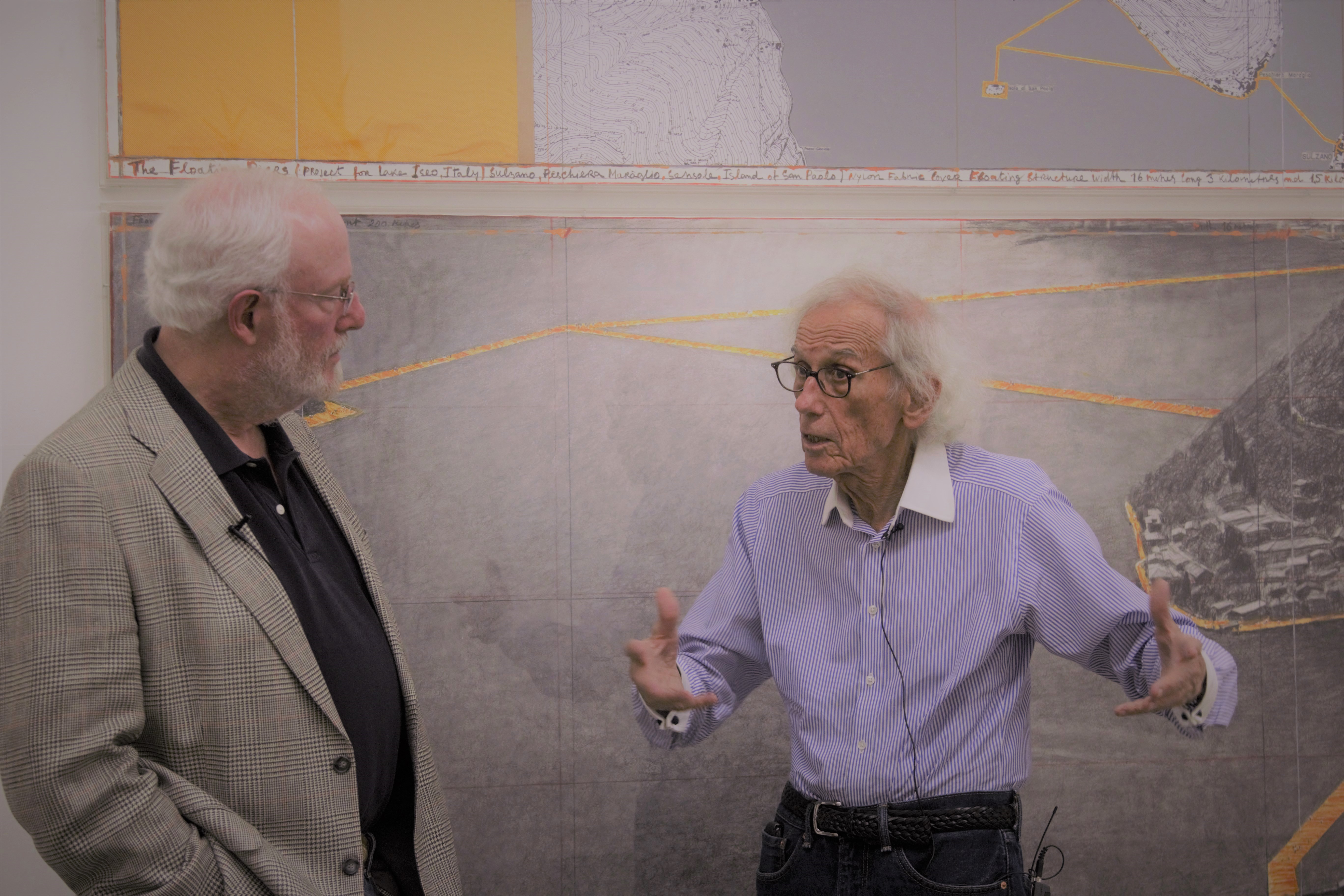

Jonathan Fineberg talking with Christo, a member of the advisory council and a model of the kind of creative thinking to which Fineberg hopes his students will aspire. Image courtesy Jonathan Fineberg.

Earlier this year, the University of the Arts in Philadelphia debuted a PhD program based on the premise that creative thinking lies at the heart of innovation in all fields. A low-residency degree for advanced interdisciplinary research in the arts, humanities, sciences, and social sciences, the PhD in Creativity seeks to fundamentally change the way students think about research problems. The program offers intensive immersion in creative thinking, cross-disciplinary workshops for dissertation development, and a bespoke dissertation committee tailored to best serve each student’s individual dissertation project. The first cohort of students are applying now to begin in the summer of 2019.

HOW DID IT COME ABOUT?

David Yager and Jonathan Fineberg met in 2015 at a conference on cross-disciplinary thinking in art and science sponsored by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (part of the National Academies Keck Futures Initiative). Well known for his pathfinding work in medicine and design, the academies had asked David Yager to serve on the steering committee. The organizers asked Jonathan Fineberg to speak about his new book Modern Art at the Border of Mind and Brain, which crosses psychoanalysis and neuroscience with art criticism for a fresh perspective on the nature of creative thinking. At this conference, Jonathan and David began a conversation that led to their collaboration in creating this radically reconceived PhD.

HOW DOES IT WORK?

The PhD in Creativity commences in mid-June each year with an intensive, two-week residency in a curated sequence of arts experiences interspersed with 4 days of methods seminars. Students also begin to workshop their individual PhD projects during this time with support from their cohort and from the Program Director.

The students meet again over a long weekend the following January, and again the following summer as they enter the final stages of research and begin writing in the second year. Most PhD programs commence with two or three years of training in methods and of mastery in the specialized knowledge of a discipline and then they administer a qualifying exam to determine if a student is ready to go on to the dissertation stage of the PhD. At University of the Arts, the PhD program looks at the MA-level training (done elsewhere), together with work experience, and a dissertation proposal as a kind of qualifying “exam” for admission and begins the program at the dissertation stage. The proposal must be interdisciplinary, preferably the kind of hybrid project that would not quite fit another PhD program. In the first summer, the cohort of peers from different fields and the program director critique each proposal in a workshop, set in the midst of a creativity immersion that attempts to break down the hierarchies of conventional training. Then a dissertation committee is formed around the needs of each student’s specific project, recruiting advisors from wherever the right advisors are to be found.

INTERVIEW WITH JONATHAN FINEBERG, Director of the PhD Program

CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske corresponded with program director Jonathan Fineberg earlier this year to hear his insights. Read their interview below.

JTP: Who do you see applying to the program? What is the sort of background/research would you like to see them coming in with?

JF: I’m already seeing, in the initial inquiries, exactly the kind of applicant I was hoping for: someone with a solid training in a field, and real experience putting their skills into practice, who then realizes they have an idea of how they might do things differently. I expect they will come with an MA, an MD, a law or business degree and have found a particular, hybrid project they’d like to explore for which they weren’t trained. I spoke with an extremely talented law school provost, for example, who is thinking about how the training of law school deans and presidents shapes the profession and I expect she’ll write an innovative book from this dissertation; a brilliant dancer with great performance experience came to me thinking about how dance companies are increasingly redefining themselves around discrete projects rather than continuing as companies and what that means both for the future of dance and for our culture more broadly; I spoke with a researcher at a drug company looking for a fresh angle on Alzheimer’s disease; and an experienced educator who is thinking about curricula for non-traditional learners. These kinds of projects will all be looking to a range of sometimes completely novel practices to infuse their investigations with fresh air.

JTP: The timeline of three years to completion is impressive.

JF: Both because these students are a little older and highly motivated and because the advising is carefully orchestrated and very hands-on, we expect the dissertations to move along more quickly than is often the case. Though in many programs you can complete the dissertation in three years after you finish the MA; it’s just that we effectively outsource the MA and ask for a little more real world work experience before you start.

JTP: The advisory council for the program is diverse in discipline – how did that come together?

JF: The people on my advisory council are all extraordinarily creative individuals who embody exactly what I hope my students aspire to as innovative researchers. So, these people serve both as inspiration and also as resources for great advice about how to build this program and where to find the right advisors for the students’ projects. Because I’ve had a long and varied career myself, I’ve encountered many remarkable people in a wide variety of fields whom I know well enough to ask for their thoughts.

JTP: How do you see the location of University of the Arts in Philadelphia informing the program?

JF: Although the program will take students in any field, it resides in an art school precisely because no one is better than artists at breaking down conventional thinking. If you’ve been well trained in a field it takes years to get over that training. It’s not a bad thing to be trained well, but we hope to instill more irreverence at the start.

JTP: The “curated sequence of arts experiences for an intense course in creativity” is very intriguing! What sort of arts experiences?

JF: Imagine yourself walking into a session of jazz drummers improvising and then having them hand you the sticks; you’d have to think fast and experiment to take over. That’s the kind of experience. Imagine hearing a major artist relive the thought process from which she or he generated a work or have a gifted theater director show you how to find a character within your own personality in the morning and then trying to create a performance for that character in front your group in the afternoon. Students will by and large have no tools for these kinds of experiences, forcing them to create a structure in their own heads to bring coherence to the experience. University of the Arts in particular has an array of talented artists who can create these sorts of simultaneous baffling and exciting experiences and because they will come one after another in a compressed time period the students will get faster at adapting and responding. This will also reinforce the effect of having really smart non-specialists cross question you about your project: you can’t use field jargon and you have to make sense. That will be happening in the workshops in the midst of the immersion course and the unusual methods readings.

JTP: What made you create this program?

JF: When I met David Yager, he was on his way to become the new President of the University of the Arts after having been a very successful dean at the University of California – Santa Cruz for some years. I had just retired from The Phillips Collection and the University of Illinois where I had been supervising PhDs for forty years. I was thinking about what to do next because I wanted to try something new in a new place just to mix things up for myself. In Modern Art at the Border of Mind and Brain I had attempted to make a scientifically grounded argument that we need works of art to develop our creative response to the world; I tried to show the evolutionary basis of art. That prompted David and I to start talking about how we could teach creativity in a PhD program to produce more creative researchers in whatever field they happened to be in. This is that program.

JTP: What would you say to naysayers of an expanded program like this one?

JF: This program is not for everyone. It’s great to be an outstanding practitioner in an established field. But for this, you have to have had the experience of coming up against the limits of your training, to feel that you have an idea that you weren’t prepared to deal with, and to believe you can create something really new. I’m excited to meet these new students!

New in caa.reviews

posted Jun 22, 2018

Carol Damian reviews Heaven, Hell, and Everything in Between: Murals of the Colonial Andes by Ananda Cohen Suarez. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Cindy Teresa Peña writes about Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910–1950 edited by Matthew Affron, Mark A. Castro, Dafne Cruz Porchini, and Renato González Mello. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Brigit Ferguson discusses Gothic Sculpture in America III: The Museums of New York and Pennsylvania, edited by Joan A. Holladay and Susan L. Ward. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Wyeth, Terra, and Millard Meiss Publications Grants Open for 2019

posted Jun 21, 2018

We’re pleased to announce the opening of three publications grants for 2019, the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Grant, the Wyeth Foundation for American Art Publication Grant, and the Millard Meiss Publication Fund.

Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Grant

The 2019 Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Grant provides financial support for the publication of book-length scholarly manuscripts in the history of American art circa 1500–1980. The grant considers submissions covering what is the current-day geographic United States.

The deadline for letters of intent is September 15, 2018. Awards of up to $15,000 will be made in three distinct categories:

- Grants to US publishers for manuscripts considering American art in an international context

- Grants to non-US publishers for manuscripts on topics in American art

- Grants for the translation of books on topics in American art to or from English.

Learn more about the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Grant.

Wyeth Foundation for American Art Publication Grant

Since 2005, the Wyeth Foundation for American Art has supported the publication of books on American art through the Wyeth Foundation for American Art Publication Grant, administered by CAA.

For this grant program, “American art” is defined as art created in the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Eligible for the grant are book-length scholarly manuscripts in the history of American art, visual studies, and related subjects that have been accepted by a publisher on their merits but cannot be published in the most desirable form without a subsidy.

The deadline for the receipt of applications is September 15 of each year. Learn more about the Wyeth Foundation for American Art Publication Grant.

Millard Meiss Publication Fund

Twice a year, CAA awards grants through the Millard Meiss Publication Fund to support book-length scholarly manuscripts in the history of art, visual studies, and related subjects that have been accepted by a publisher on their merits, but cannot be published in the most desirable form without a subsidy. Thanks to the generous bequest of the late Prof. Millard Meiss, CAA began awarding these publishing grants in 1975.

Books eligible for a Meiss grant must currently be under contract with a publisher and be on a subject in the arts or art history.

The deadlines for the receipt of applications are March 15 and September 15 of each year. Learn more about the Millard Meiss Publication Fund.

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted Jun 20, 2018

Christo’s floating sculpture The London Mastaba, made from thousands of stacked oil barrels, in Hyde Park, London. Image: David Azia/NYT

Can the Glasgow School of Art Be Saved after Second Fire?

Artists and architects in Scotland say that the school may be beyond repair after a devastating fire tore through the landmark building on June 15th. (The Art Newspaper)

Bronx Museum of the Arts Hires New Director

Deborah Cullen, director of the Wallach Gallery at Columbia University, will be the next director of the Bronx Museum of the Arts. (New York Times)

Artists Support Themselves Through Freelance Work and Don’t Find Galleries Especially Helpful, New Study Says

A study based on a survey of more than 1,000 practicing visual artists sheds light on the economics of making art. (Hyperallergic)

Christo’s Latest Work Weighs 650 Tons. And It Floats.

The London Mastaba, Christo’s first major outdoor work in Britain, is now floating in the middle of Hyde Park. (New York Times)

Behind the Fierce, Assertive Paintings of Baroque Master Artemisia Gentileschi

Gentileschi was as self-made and as independent as was conceivable in her time—and she fought hard for it. (Artsy)

What It Means When Beyoncé and Jay-Z Take Over the Louvre

The surprise music video quickly went viral. (The New Yorker)

Call for Responses | Beyond Survival: Public Funding for the Arts and Humanities

posted Jun 19, 2018

Art Journal Open seeks 500-word responses for a Forum on Public Funding for the Arts and Humanities, convened by Sarah Kanouse, Jeremy Liu, Catherine Morris, and Mimi Thi Nguyen.

Moderated contributions will be posted to an online forum hosted by Art Journal Open. Some respondents may subsequently be invited to expand their text into a longer article.

Responses will be accepted through August 20, 2018 to: publicfundingforum@gmail.com

Beyond Survival: Public Funding for the Arts and Humanities

Three decades into the long culture wars, how are artists, scholars, and cultural organizations navigating shifting political, community, and financial tides? Where have we encountered friction or congruence between federal priorities and our work at state, local, and community levels? Has our work changed – in structure, presentation, or substance – in response to these priorities?

Despite threats of elimination earlier in the year, federal funding for the arts and humanities has been preserved—at least for now. While rightly celebrating this collective accomplishment, we must also acknowledge that ideological pressures on US cultural policy are performed as much through selective funding as outright defunding. Each successive presidential administration has stamped its particular priorities on funding agencies, shaping arts and humanities research through both direct and indirect means. The grantmaking models now used by the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities were carefully devised to avoid the headline-grabbing controversies of the 1980s culture wars while articulating the value of the arts and humanities to a non-elite, often skeptical public. Simultaneously, arts and scholarly communities have sometimes struggled for diversity in terms of race, class, and gender. Nonprofit cultural and educational institutions evolved alongside twentieth-century funding models, with diminishing federal funding giving way to support from private philanthropy, and its concomitant priorities. Surviving funding programs often expect artistic and intellectual activities to contribute to community development, shore up fraying social services, or emphasize their policy implications—a challenging charge made more difficult by the patchwork of fragile social, economic, community, and technological infrastructures on which such work rests.

In an environment of heightened scarcity and competitiveness, how do we negotiate the differing audiences, priorities, and compromises that inevitably register in creative, academic, and public discourse? How do we defend our existing, imperfect, imperiled institutions while also calling for—and ultimately achieving—more expansive public funding of a wider range of aesthetic and political voices?

We seek 500-word responses to these questions from communities of art-making, scholarship, and exhibition practice. Moderated contributions will be posted to an online forum hosted by Art Journal Open. Some respondents may subsequently be invited to expand their text into a longer article. Responses will be accepted through August 20, 2018 to publicfundingforum@gmail.com.

Sarah Kanouse

Artist and Associate Professor

Department of Art + Design

Northeastern University

Jeremy Liu

Senior Fellow for Arts, Culture and Equitable Development

PolicyLink

Catherine Morris

Senior Curator for the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art

Brooklyn Museum

Mimi Thi Nguyen

Associate Professor

Gender and Women’s Studies and Asian American Studies

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

New in caa.reviews

posted Jun 15, 2018

Ellen Handy reviews Clarence H. White and His World: The Art and Craft of Photography, 1895–1925 by Anne McCauley. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Jenifer Neils writes about The Image of the Artist in Archaic and Classical Greece: Art, Poetry, and Subjectivity by Guy Hedreen. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Eric Michael Wolf discusses Austin by Ellsworth Kelly, and the exhibition Form into Spirit: Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin at the Blanton Museum of Art. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

Christopher Kasprzak explores the exhibition Calder: Hypermobility at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Read the full review at caa.reviews.