CAA News Today

An Interview with 2018 Keynote Speaker Charles Gaines

posted by CAA — Dec 13, 2017

CAA 2018 Annual Conference Keynote Speaker Charles Gaines is a Los Angeles-based artist whose complex grid-work and mapping pulls from conceptual art and the field of philosophy. His work is currently on view at ICA Miami, at Cornell Fine Arts Museum, at kurimanzutto in Mexico City, and he has an upcoming show at Galerie Max Hetzler in Berlin. CAA media and content manager, Joelle Te Paske spoke with Charles about what he’s working on, his teaching at CalArts and Los Angeles in 2017, and if artists can change the world.

CAA’s Annual Conference Convocation, including the keynote address and presentation of the Awards for Distinction, will occur February 21, 6:00-7:30PM and will be livestreamed.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

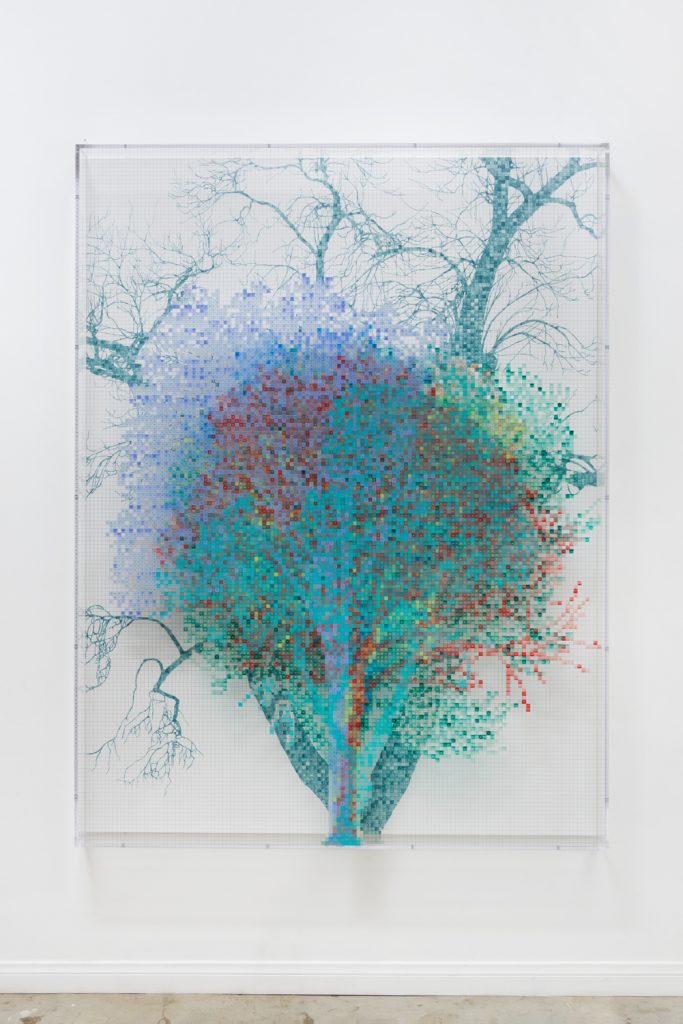

Charles Gaines, Numbers and Trees: Central Park Series 2, Tree #7, Maria, 2017. © Charles Gaines. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Joelle Te Paske: I read the interview that you did for your Studio Museum exhibition in 2014 and you said: “I use systems in order to provoke the issues around representation.” I’m curious about how you’re thinking about systems right now in 2017.

Charles Gaines: I work with systems and structures, which results in the fact that the work itself is rule-based. My interest in it is really a suspicion about standard ideas of subjectivity. I felt that when I was in graduate school, the way we talked about art, seems that it was based on the assumption that the art object itself was a kind of access to the subjectivity of the artist. I got suspicious about [that] idea in modernism. That the purpose of art is, at its most essential core, a subjective practice, and if you take subjectivity out of it, you’ve eliminated or eviscerated the idea of art itself.

I wasn’t necessarily opposed to the concept of aesthetics itself, but again, when it became the principal and core purpose of a work of art, I had a lot of problems with that—to produce this aesthetic object—because that brings up issues of culture. And so, I was saying that aesthetic effects can be produced not by one’s intuition, but they can also be produced by rational strategies and intellectual, productive strategies, and one can have the aesthetic experience that’s a product of that. It’s a way of challenging the notion of how representation works in works of art.

JTP: It’s finding an alternative route into meaning, essentially. It gives you a different pathway.

CG: Yes.

JTP: Do you have a memory of first noticing a system—I’ve read that you’re interested in Buddhist teachings—that you hadn’t considered before?

CG: I was introduced to two books, one by Ajit Mookerjee which is called Tantra Art, and the other is Henri Focillon, The Life of Forms in Art. Buddhist works are interesting to me because the monks made works of art, but had no concept of the unconscious.

JTP: Interesting.

Charles Gaines. Photo: Katie Miller

CG: The personal subjectivity, they did not privilege that. But nevertheless, they have an art practice, made sculptures, drawings, and so it was interesting, because I had had to go outside the Western paradigm in order to discover that there are other ways of making work. And another thing that interested me about that is that the effect of that kind of process, this kind of sublime exhilarating experience, where you don’t actually have control over what you’re doing, because either the system has control of it or chance has control of it. And so you’re in this space that is to me way more interesting.

JTP: Yes, I’d say there’s a different kind of freedom to be found there.

If you could recommend one book to students or artists that they probably haven’t read, what would you recommend?

CG: Right now, books that deal with the postcolonial. Books that allow you to think about the relationship of art and culture, and the way that challenges assumptions of modernism. In my particular case, a very important book is Fred Moten’s [and Stefano Harney’s] The Undercommons, because of the way [Moten is] trying to negotiate what blackness means. It’s quite different from certain sociological or essentialist ideas of that subject.

JTP: Thinking about your role at CalArts, what are the changes that you’ve seen as part of the faculty?

CG: CalArts has managed to maintain, to some degree, the kind of reputation of an art practice that is not the standard. I was talking to some people about this the other day, and in particular Europeans generally think that CalArts is the most elite of art schools. They think that it’s among the best schools in the United States, but the reason why is because the school privileges ideas and challenges notions of certain standard practices. There’s a general suspicion of the idea of mastery.

JTP: That’s beautifully put.

CG: I mean, a lot of schools have developed programs or disciplines called new genres. So they’ll have painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking, and the new genres. And so new genres is, I think, supposed to deal with the issues that are conceptually driven in works of art. You know, in particular, the avant-garde.

CalArts was invented with that kind of idea, and so I still think it’s a bit radical. Which blows me away actually, because I still get into discussions with other professionals, not so much in the art world, but certainly in academia, about whether the role of mastery informs curriculum. In our Masters program, we get the students who never really challenged the idea of mastery. In the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, there was the idea of art as an avant-garde practice; it wasn’t something that was controversial. It’s sort of a weird reversal of history, that the idea of art as an avant-garde practice is becoming more and more provocative. Particularly in the way people are thinking about educational systems and curriculum development and so forth. It’s the idea that they haven’t really come into the framework experienced in critiquing the idea of mastery with respect to works of art. I guess that’s the largest change that I’ve seen.

JTP: Yes, I think that your comment about the longer view of the history and the purpose of art is interesting, because history repeats itself and reconfigures itself.

When you’re working with students, what are you most excited about?

CG: In terms of what I enjoy in the experience of teaching at CalArts, we are lucky to get really good students. And the graduate students tend to be a little older and so, you wind up having the richest seminars—critical discussions about works of art, where the teaching goes two ways. I learn from them, they learn from me.

JTP: That’s terrific.

CG: You know, that keeps it quite vibrant and alive. There is a transition that the art students have to go through to get to that point where their criticality can reach a more sophisticated level. Their first year, [that] tends to be pretty traumatic for them. The dismantling of a lot of their assumptions about art. But through this process, they segue into the ability to be quite intelligent and quite interesting [in] the way they ultimately critique ideas and each other’s work.

Charles Gaines, Manifestos 2 (Installation), 2013. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Steven Probert © Charles Gaines. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

JTP: I’m curious too about LA. I know that you’re a longtime resident of the city—if you had to choose one thing for people coming to the conference, what you would recommend?

CG: LA has a remarkable list of museums, mostly contemporary art museums and modern art museums. Nobody should miss that. The art scene in LA is just generally interesting. I can also easily make a plug, because I’m on the board of the new ICA LA (Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles). People should make sure not to miss the ICA LA.

JTP: Thank you, that’s great. I know too that you’ve been part of the debate in Boyle Heights about art spaces and gentrification, and there’s been dialogue on all sides about it.

CG: I got caught up in the whirlwind of that. In this particular instance, the artists who’ve been moving into Boyle Heights in the last five or 10 years or so formed an alliance with a particular group of Latino artists to form a new strategy to fight gentrification. I was sort of upset by the fact that they’re attacking some very progressive alternative spaces.

In Boyle Heights, there’s a legitimate effort to fight gentrification that follows a history of certain strategies of fighting it that are unique to minority communities. In other words, Boyle Heights is a depressed community and was formed not because Latinos and Black people wanted to live there; it was formed because of redlining. And so those people, they want to stay in Boyle Heights, but they want it improved. And so their strategy against gentrification includes finding ways where they can increase their voices in terms of how this plays itself out. But this other group does not want any improvement. They just want to stop it.

They’re not interested in the idea of improvement, so what I said was that the artists who moved to Boyle Heights must recognize that they’re the first stage of gentrification. And I said that they were appropriating and colonizing the interests of the minority community.

JTP: You’re saying development could be good, it should be driven by the people who have been living there. They should have input and they should be guiding it.

CG: Whether it’s good or not, it’s inevitable.

JTP: It’s inevitable; okay that is a good distinction.

CG: There isn’t history where these kind of things, where gentrification was essentially stopped. What happened is that it was controlled.

JTP: We definitely want people coming from out of town to be aware of what is happening in Los Angeles. It’s helpful to hear your perspective, because you’ve lived there a long time and you’ve been active and involved, so thank you.

By the way, have you attended CAA conferences in the past?

CG: Absolutely. In fact, I’ve even been on a couple of panels. Several times in the past. There’s such a wide variety that’s available to see. I think it is very, very important to maintain that diversity and I have been noticing the increase in social and cultural issues.

Joelle: That’s definitely something we’re working on here at CAA.

I do have one more question, and it’s my favorite. Please feel free to answer it however you’d like. Do you think artists can change the world?

CG: I mean, it’s a cause and effect thing. Artists can change our ideas about art. But artists can also play a role in changing our ideas about society. They can play a role in that, like the activism that artists [did] in the 1970s helped to increase the number of women and minorities in art. And that comes from not only artists dealing with politics, but at the same time culture in general, a critique of male dominance and white male dominance, so artists play a role with other forms of social activism in changing things. It’s not like you can make a work of art and everybody’s just like “Oh, okay, I feel differently now.”

I think that people who make the argument that artists can’t change things—the phrase itself makes no sense to me. But the people who make that argument make it under the assumption—this is why Fred Moten’s The Undercommons is such an important book—of a simplistic notion about what politics is and how it works.

JTP: I agree. It’s my favorite question, because I very much believe that artists play a role in doing so.

This has been a rich discussion, thank you for taking the time. Is there anything else that you’d like to add in for people reading this?

CG: It’s a pleasure talking, and I’m looking forward to the event. I don’t know what I’m going to talk about yet, but I’ll think of something.

JTP: Yes, from this conversation, I have a feeling you definitely will.