CAA News Today

New on Art Journal Open

posted by CAA — June 13, 2018

Elisabeth Smolarz, ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THINGS, 2014- (ongoing). Archival inkjet prints, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

Caitlin Masley-Charlet in Conversation with Elisabeth Smolarz

This interview is the last in a series of conversations led by Caitlin Masley-Charlet, focused on the utility and scope of artists residencies. In this interview, Masley-Charlet sits down with artist Elisabeth Smolarz to discuss Smolarz’s recent residencies and projects, and the importance of failure, artistic community, and cross-pollination between practitioners.

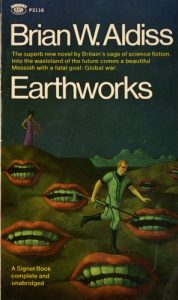

Brian Aldiss, Earthworks, Signet paperback, 1967

Digging into Aldiss’s Earthworks and Smithson’s “Earthworks”

Scholar Suzaan Boettger looks at the generative interplay between the science-fiction novels of the late Brian Aldiss and the Land art works of Robert Smithson, examining the word “earthworks” as a “shared emotional bedrock” between the two artists. In looking at Aldiss and Smithson side by side, Boettger brings Aldiss’s work more into the realm of art history, and Smithson’s work more into the realm of science fiction and environmental degradation.

How to Become an Art Editor: An Interview with Phil Freshman, President of Association of Art Editors

posted by CAA — June 12, 2018

Freshman’s home office. All photos courtesy Phil Freshman.

Phil Freshman is a freelance art editor and president of the Association of Art Editors (AAE). Formerly a staff editor at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1980–84), the J. Paul Getty Museum (1985–88), the Walker Art Center (1988–94), and the Minnesota Historical Society Press (1995–99), he has worked on numerous books, exhibitions, and other projects, focusing mainly on art history, architecture, photography, and design.

We were curious what advice Phil might have for aspiring art editors. CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske spoke with him in April 2018.

Joelle Te Paske: I’m glad we have a chance to talk, especially to learn more about the Association of Art Editors and take a look at what you do.

Phil Freshman: When I talk to people about the AAE who didn’t know about it previously, they’re typically glad to know it exists.

JTP: It’s great. So, what are you working on nowadays?

PF: The last catalogue I edited was for the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, which recently took the “s” off its name and started calling itself “Mia.” Anyway, the book was about contemporary Japanese lacquer sculpture, and was tied to an exhibition that is on view now and will be up until late June. It’s a field of study I had never thought about much. You think of Japanese pottery, right? But you don’t think of pure sculpture. A very interesting and challenging project.

Right now, I’m editing a memoir by a lifelong friend who recently retired from the law. He spent a year hoofing it around West and East Africa in the early 1970s and thought he would get around to writing a memoir right afterward. Then 45 years went by like the wave of a hand, and here he is, doing it now. So, it’s a pleasure to help him, to know enough to make his manuscript better.

JTP: You’re learning a lot about him, I bet.

PF: I am. And that was a part of his life I hadn’t known much about to begin with.

JTP: How did you become an editor?

PF: I was a Los Angeles lad who first wanted to be a newspaper reporter. But despite trying for several years, it didn’t work out. I then lived for three uninterrupted years in Israel, Iran, East and West Africa, and Spain, finding ESL teaching jobs along the way. I came back home to get an ESL degree at UCLA. During that time, a friend in LA whose firm published books dealing with Western US history hired me part-time to review slush pile manuscripts and proofread book galleys.

A couple of years later, with just that little bit of experience but intrigued by the work, I applied for a copyeditor-proofreader job at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. I took the required test (along with something like 200 other applicants), was interviewed, and then hired. I thought, “Oh, God. Now I actually have to do something.”

JTP: Yes, now it was real!

Ralph Rapson: Sixty Years of Modern Design (1999). Freshman edited this and the other books illustrated here.

PF: At first, I had no idea what I was doing. But my senior editor was a great teacher. When he left the museum—too soon, alas—I was the only editor there. I worked on books about American painting and printmaking, 18th-century fashion, contemporary art, and more, plus the monthly members’ magazine, annual reports, lots of brochures, flyers, exhibition labels. It was full immersion and very long weeks until, after six months, I was allowed to hire somebody. Eventually, I had three editors.

JTP: That makes sense. Rather than just one, working at that scale.

PF: Right. But when I was hired from the Getty Museum to be the Walker Art Center’s first-ever editor, in 1988, I was once again a solo act—and remained one for three years. The Walker had an ambitious program of publishing catalogues and presenting exhibitions on the history of graphic design, Russian Constructivist art, contemporary sculpture, and this, and that, and the other thing! All that plus editing for the Walker’s very active film, performing arts, and PR departments. I worked 70 to 80 hours a week, and that didn’t stop even after I was finally able to hire an assistant editor.

JTP: There was no getting around the fact that you had to go through all that material.

PF: Right. Not just going through it all but also needing to be attuned to a constellation of details. That was, as it so often is, the job—the details, as well as panning out for the whole picture. And more often than not, I didn’t receive all the materials I needed at the get-go. Unfortunately, that’s all too typical in this racket. In fact, sometimes you get a little bit, and then some more dribbles in, then a bit more, and you have to assemble the material as it’s unfolding before you, make everything hang together. I had to develop a host of skills over the years, including diplomacy—at which I’ve never been adept.

Beyond all that, one reason I was initially attracted to editing was that I had no patience for formal schooling. I’ve found that editing has provided a rich, ongoing education in which I get a front-row seat to subjects about which I might otherwise never have learned a thing. Not to mention exposure to fascinating people, and to situations I wouldn’t have encountered if I weren’t doing this work. There are certainly things to hate about it, but the balance sheet works out in its favor.

JTP: It’s so detail-oriented, but you are committing your time to new projects and scholarship. It’s integral to the work.

Dining with the Washingtons: Historic Recipes, Entertaining, and Hospitality from Mount Vernon (2011).

PF: Yes. And I also keep coming back to this: you have to keep asking questions. One instinct that made me want to be a reporter applies perfectly to editing. I ask questions, and then ask more, and then ask some more. Often enough, I’ve had authors and curators who are responsive to that. The relationship works best when they understand that I’m on their side, trying cover any holes that open up because they were writing too fast. But some of them are resentful, insecure, brittle, and they can make that sort of thing difficult.

JTP: Yes, I can see it going both ways. I would think, though, that writers with more experience realize having a good editor can be like a good friend, someone who can make your work better before it goes out into the world.

PF: That’s it. I’ve worked with a few pretty well-known authors with whom it felt like a collaboration. They liked the back-and-forth. They didn’t just take all of my suggestions but said, “No, let’s discuss this further.” And then you get to a middle way that’s better than what you thought of, or than what they thought of.

JTP: Would you recommend that editors who are just starting out keep that in mind?

PF: Definitely. Another thing I like to tell aspiring editors is, “Go to the library.” You know, the library?

JTP: I’ve heard of those.

PF: [Laughs] Get hold of exhibition catalogues and other art books on a range of subjects, and then review all the separate essays or chapters, the footnotes and bibliographies, the plates, figure references, checklists, and the rest. And bear in mind, as you’re reading, that it’s highly unlikely that the original manuscript was delivered intact to the editor at beginning of the process. Probably dribbled in over a period of weeks, if not months.

You have to take the bits and pieces and make them fully consistent, factually accurate, grammatically correct, and maybe even interesting! So, I don’t know that someone has to have an art background per se in order to be an art editor. But I would say that having a feel for and a knowledge of language, a willingness to become genuinely invested in a subject, a good visual memory, and an insane attention to detail are all necessary.

JTP: I imagine AAE would be a great resource for people starting out. Where else should they look?

PF: LinkedIn is a good source. The old cold-call approach is not bad. Find people who work where you might want to work and contact them. I recently spoke with an editor friend who, though she had just quit Facebook, found a valuable online organization on it called Editors’ Association of Earth. She described it as a private, heavily moderated group and a place where you can engage with other editors, ask questions freely, and get advice.

JTP: Editors likely want to share their skills—many have devoted their careers to sharing knowledge, after all—and it seems like that would be good for people starting out.

PF: I’d also suggest getting immersed in The Chicago Manual of Style. And finding books about editing. Here are some I recommend:

- The Subversive Copy Editor, by Carol Fisher Saller. University of Chicago Press, 2009. Her monthly online Q & A, via the U of Chicago Press Website is terrific. Need to sign up for it.

- Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach, by Beverly Serrell. Rowman and Littlefield, 2015 (second edition).

- Line by Line: How to Improve Your Own Writing, by Claire Kehrwald Cook. Houghton Mifflin, 1985. (This is the one I have, but there are probably subsequent editions.)

- On Writing Well, by William Zinsser. Collins, 2006 (30th anniversary edition).

- The Copyeditor’s Handbook: A Guide for Book Publishing and Corporate Communications, by Amy Einsohn. University of California Press, 2006 (second edition). A very good primer on the basics. It also includes copyediting exercises and answer keys.

JTP: That’s terrific. Thank you.

Toward a Simpler Way of Life: The Arts and Crafts Architects of California (1997).

PF: I’d also suggest that if a nearby college offers copyediting classes, take one. It can be very useful to learn the mechanics in a formal way. Such classes also help you see whether or not you have an appetite and instinct for editing.

JTP: This is important, too, because it’s an intensive practice.

PF: Right. Once you get involved in a job, it’s immersive. It is the writer’s book, the museum’s book, the publisher’s book, but you can’t ever say to yourself, “Well, it’s on them. I wash my hands of this,” or, “It’s not going to have my name on it.” You have to feel responsible for whatever project you’re on. In other words, you can’t say, “It’s just a job.”

Another thing to consider: Back in the days when I had stars in my eyes, I’d think, “How wonderful it would be to work for XXX Museum of Art. So prestigious.” But in fact, some of my best experiences have been with smaller institutions and some of my worst with larger, “important” ones.

JTP: That’s good to know.

PF: Usually, there are good people in such places. Sometimes a good attitude. Less bureaucracy. And often you can get things done more fluidly.

Another thing important to me is having solid relationships with graphic designers. I’ve worked with good ones and very bad ones. By good, I mean ones who like to share suggestions about what might work, ones who welcome it when you point out why a certain typeface, or size of type, or caption location in relation to pictures might be reconsidered. It’s a conversation. And then on the other hand, there’s the head-banging-against-the-wall experience of having to deal with the other kind of graphic designer. One of them referred to text as “texture,” something mostly useful as a visual complement to their brilliant layouts!

JTP: As an editor, I can only imagine [laughs]. Do you ever work in tandem with a graphic designer, presenting yourselves to a client as a team?

PF: Yes. Several designers I know will get a job and say to the client, “I know a good editor in Minneapolis. I’d like you to hire him.” By the same token, I’ll get a job and ask, “Do you have a designer for this?” If the client says no, I’ll offer contact information for three or four designers, making my top preference clear.

JTP: Good to know. Keeping track of the designers you like working with would help you establish a mutual-support system.

PF: That’s right. It helps you feel more comfortable going into a project—you know that you can kid around with the graphic designer, and that you can bitch about the client without worrying it’s going to get back to them.

JTP: Can you name a highlight of being president of AAE? Also, how long have you been president?

PF: I’m president for life [laughs].

The General in the Garden: George Washington’s Landscape at Mount Vernon (2015).

JTP: [Laughs] Like a Supreme Court justice.

PF: You got it. I’ve occasionally had thoughts of not doing it anymore, but it’s not [too taxing]. Well, creating the first version of our soup-to-nuts style guide, in 2005 and 2006, which I did in tandem with three other editors whom I greatly respect—that did take months. But the result was just wonderful. I’m really proud of having done that. And I get lots of good feedback. Also, I like helping editors find work through the job opportunities page.

There’s also a section [on the AAE site] called Helpful Links. It has many sources you might want to refer to as you’re doing research for a book or an exhibition you’re editing.

The site is an open-source one. Anyone can use it freely. One AAE offering not visible on the site, however, is the rates survey we conduct every five years. It includes questions such as “How much do you charge for editing, proofreading, and other separate tasks?” And “Do you charge extra for working on weekends?” Among numerous others. We sort the answers, and provide a report with graphed percentages and selected verbatim responses.

JTP: That’s terrific. Sounds like it would help editors advocate for themselves.

PF: That’s the idea, of course. I don’t post rates-survey reports on the website because I don’t want potential clients, such as curators, browsing them and thinking, “Wow! Looks like I can get away with paying somebody $20 an hour!” But I’m happy to send the reports out to anybody who requests one.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Apply for the 2019 CAA-Getty International Program

posted by CAA — June 11, 2018

Nomusa Makhubu, University of Cape Town, chair of the “Border Crossings: The Migration of Art, People, and Ideas” alumni panel at CAA 2018. Photo: Rafael Cardenas

The CAA-Getty International Program, generously supported by the Getty Foundation, provides funding to between fifteen and twenty art historians, museum curators, and artists who teach art history to attend CAA’s Annual Conferences. The goal of the project is to increase international participation in CAA, to diversify the association’s membership, and to foster collaborations between North American art historians, artists, and curators and their international colleagues.

ABOUT THE 2019 GRANT

The 2019 CAA-Getty International Program will support fifteen art historians, museum curators, and artists who teach art history to attend the 106th Annual Conference, taking place in New York City from February 13-16, 2019. The grant covers travel expenses, hotel accommodations for eight nights, per diems, conference registrations, and one-year CAA memberships. The program will include a one-day preconference colloquium on international issues in art history on February 12, at which grant recipients will present and discuss their common professional interests and issues. Attendance at the preconference is limited and by invitation only. This year the grant also will fund five alumni from the CAA-Getty International Program to participate in the preconference colloquium and speak at a session during the conference. As they have in previous years, representatives from CAA’s membership will host program participants during the conference week.

ARE YOU ELIGIBLE?

Applicants must be practicing art historians who teach at a university or work as a curator in a museum, or artists who teach art history. They must have a good working knowledge of English and be available to participate in CAA events from February 12-16, 2019. Only professionals who have not attended a CAA conference previously, and who are from countries underrepresented in CAA’s membership are eligible to apply. The grant excludes scholars from North America, Western Europe, and Australia, whose countries are well represented in CAA. It further excludes scholars who have received funds from American foundations or research institutes to participate in conferences or residencies in the United States. Applicants do not need to be CAA members. This grant program is not open to graduate students or to those participating in the 2019 conference as chairs, speakers, or discussants.

HOW TO APPLY

Please review the application specifications and complete the application form. PLEASE NOTE: In order to apply, you need an temporary Member Number, which you get by contacting Member Services. If you have questions about the process or are unsure of your eligibility, please email Janet Landay, project director of the CAA-Getty International Program.

Applications should include:

- A completed application form

- A two-page version of the applicant’s CV

- A letter of recommendation from the chair, dean, or director of the applicant’s school, department, or museum

Applications must be submitted no later than Monday, August 27, 2018. Only applications submitted via the online form will be considered. CAA will notify applicants by Friday, October 5, 2018.

New in caa.reviews

posted by CAA — June 08, 2018

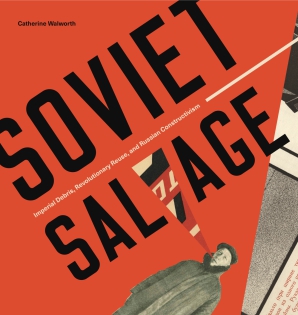

Samuel Johnson writes about Soviet Salvage: Imperial Debris, Revolutionary Reuse, and Russian Constructivism by Catherine Walworth. Read the full review at caa.reviews.

CWA Picks for June 2018

posted by CAA — June 07, 2018

Sophia Narrett, Right Before (detail), 2017-18, on view at BRIC in Brooklyn, NY, through June 17, 2018.

CAA’s Committee on Women in the Arts selects the best in feminist art and scholarship to share with CAA members on a monthly basis. See the picks for June below.

Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg

June 6–September 9, 2018

Moderna Museet

Exercisplan 4, 111 49

Stockholm, Sweden

This retrospective exhibition brings together the large-scale film, sculpture, and sound installations created by Nathalie Djurberg and her frequent collaborator, the composer and musician Hans Berg. Djurberg’s work—by turns comical and horrifying—demands close attention: power is exchanged unevenly, humans (and animals) preen, beat, and eat one another. In this situation a feminist politics may be difficult to discern, but it is there. At the heart of Djurberg’s endeavors is the uncompromising questioning of systemic power structures—whether that be religion, the state, or gender hegemony. In The Parade (2011), Djurberg populates five synced videos with birds who flock, fight, and mate; meanwhile, on the ground, dozens of free-standing bird sculptures are lined up in a procession that recalls both biblical fable and ritualistic pageantry.

New work will accompany this presentation, and it marks the first major exhibition for the artists, who were both born in Sweden.

A Woman’s Afterlife: Gender Transformation in Egypt

Ongoing

Brooklyn Museum

200 Eastern Parkway

Brooklyn, NY 11238

Access to the afterlife in the Egyptian ancient world was limited to those believed to have reproductive capacities—and astonishingly this trait was assigned solely to men. It was believed that men gestated a fetus and then, through sex, transferred it to a woman’s womb. When women died, they were depicted with male traits (red skin), and had protective spells (meant for men) incanted above their corpse and written on their coffins. This exhibition explores these gender transformative practices and more, through the choice of twenty-seven objects from the museum’s collections. As Kathlyn M. Cooney related in a recent lecture associated with the exhibition, it is not enough to consider how one of the most “totalitarian” societies treated gender and sexual difference, but to also reflect on how Egyptology is methodologically wrestling with a similar set of concerns: “Feminism in Egyptology is a strange thing, because women are encroaching to take over the field. Females are on the forefront […] What I find is often missing […] is we look for the women who had power and highlight them, in a way to make ourselves feel better about women not having power, without asking the question, more systematically, why are women excluded from power so regularly and what are the mechanisms in place?”

Décor: Barbara Bloom, Andrea Fraser, Louise Lawler

April 28—July 15, 2018

MoCA Pacific Design Center

8687 Melrose Avenue

West Hollywood, CA 90069

The centerpiece of this exhibition is the reinstallation of Barbara Bloom’s The Reign of Narcissism (1988-89), a faux period room decorated all over with the artist’s likeness. But for Bloom this was not an entrée to self-aggrandizement, but a way to work through what Mieke Bal has termed “biographism” alongside the meaning, content, and politics of design. Three tombstones, set comically in a glass vitrine, memorialize the artist before she’s dead, and chairs are upholstered with designs derived from the Bloom’s dental X-rays.

Supporting the themes of the installation (which, is also about the politics of museological display), are works by Andrea Fraser and Louise Lawler. Fraser’s Little Frank and His Carp, finds the artist sensually humping the walls of the Guggenheim Bilbao’s atrium, a response to a sycophantic audio guide. Photos by Lawler highlight the conflation of the aesthetics, display, and markets of art.

Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965-2016

April 9– July 22, 2018

The Museum of Modern Art

11 W 53rd St

New York, NY 10019

Adrian Piper’s (b. 1948) first museum retrospective in the US in a decade, and the first living artist’s show to occupy MoMA’s entire sixth floor, Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965-2016 is a timely and moving feat for a female artist of color, even though of Piper’s caliber.

Bringing together over 290 works, including drawings, paintings, photographs, mutlimedia intallations, videos and performances, it offers a powerful and exhaustive exploration of Piper’s multifaceted contribution to contemporary art, illuminating the nuances of her Conceptualism and the intricacies of her combined critique of sexism, racism and xenophobia.

The show begins twice.The installation Vote/Emote (1990), comprising a row of voting booths where museumgoers are invited to respond to various prompts—like listing “the fears of how we might treat you”—precedes its chronological unfolding, highlighting both the centrality of the audience and emotions in the artist’s conceptual and often performative critical practice. A neo-realist self portrait, featuring a black girl with a white doll from 1966, stands out among the earliest works of the first room of the exhibition that focuses on her early experimentations with painting, poignantly marking the origins of the identity politics underpinning her work. Together they make a timely statement about the little changed state of race in America in the age of Trump, and initiate a several-hours worth familiarization with the development of Piper’s multimedia practice in the past forty years that leaves the viewer mesmerized by its profound complexity, sensitivity and acumen, as well as confronted with his/er complicity with the injustices and prejudices of the world we live in.

Eija-Liija Ahtila

May 18 – June 19, 2018

M Museum Leuven

Leopold Vanderkelenstraat 28, 3000

Leuven, Belgium

Bringing together 7 major works by Eija-Liisa Ahtila (b. 1959) in multiscreen configurations especially reconceived for the M Museum in Leuven, along with several series of drawings, this exhibition surveys the filmic work of the acclaimed Finnish master of cinematic installation.

Known for her experimentation with narrative story telling, begun with unsettling human dramas at the center of human relations, in her recent works Ahtila questions the processes of perception and attribution of meaning under the light of larger cultural and existential thematics like colonialism, faith and ecological or humanitarian crisis. Encouraging us to explore how the film might enable us to narrate the very life of the planet as well as our own, a timely eco-cinematic question underpins several of her more recent works: how and with what kind of technology, drama and expressive devices can we build the image of our world in this present moment of ecological crisis?

Along with signature works produced since 2001, the exhibition includes her latest sculptural filmic masterpiece, Potentiality for Love, 2018. With a floating maternal body as its epicenter, the work questions, from a feminist posthumanist perspective, the potential for empathy and love towards other living beings, turning attention to those human emotions that could serve as a foundation for dismantling the hierarchical structures between living things, thereby engendering a turn towards non-humans and the recognition of others.

Sophia Narrett: Certain Magic

May 12- June 17, 2018

Project Room at BRIC House

647 Fulton Street

Brooklyn, NY 11217

Recipient of the 2017-8 ArtFP—an open call for Brooklyn-based visual artists to exhibit at BRIC House—and the 2018 Krasner Pollock Foundation Grant, Sophia Narrett is a recent graduate from the Rhode Island School of Design, distinguished already for her mesmerizing, quite painterly and often quite tiny, embroideries and the complexities of her story telling.

Not to miss, her solo exhibition in New York at BRIC House brings together examples that thematize the power of intimacy and desire in the digital age, by casting figures culled from the Internet into lusciously embroidered scenes, in response to a world of immediate, often treacherous media. Through undulating embroidered surfaces, and edges that dissolve into loose threads or sculptural flora, Certain Magic tells a disconcerting narrative of modern longing that layers the surreal with the mundane in a manner characteristic of the artist’s story telling intricacies. While her practice exceeds the traditional parameters of embroidery, the traditional and gendered associations of the medium are crucial to its content, and feminist fragility. As put recently by the artist “Embroidery and its implicit history help specify the tone of my stories, one characterized by obsession, desire and both the freedoms and restraints of femininity.”

Take the CAA Professional Development Survey

posted by CAA — June 06, 2018

Professional Development is very important to CAA. We strive to create programs both during the Annual Conference and at other times that address the professional needs of the visual arts field and community.

We ask that you give us your feedback on what kinds of professional development programs would work best for you.

Deadline: July 1, 2018

News from the Art and Academic Worlds

posted by CAA — June 06, 2018

Irving Sandler, Art Historian Who Was Close to Artists, Dies at 92

Art critic, historian, and longtime CAA member Irving Sandler passed away on June 2nd. (New York Times)

Museum of Modern Art Staff Protest Outside Fundraising Gala, Demanding a Fair Contract

MoMA workers and their supporters rallied outside the Museum to draw attention to ongoing contract negotiations that are currently at an impasse. (Hyperallergic)

Director Okwui Enwezor to Step Down from Munich’s Haus Der Kunst

The renowned curator and art historian announced he is resigning from his post due to health reasons. (Artforum)

Art Sold Separately: Why Are People Buying Free Felix Gonzalez-Torres Posters?

Gonzalez-Torres made his first work that includes a stack of paper in 1988, and his first to consist of a stack constantly replenished with “endless copies” in 1989. (Greg.org)

The Paintings that Turned Persian Art on its Head in the 19th Century

While Persian arts are usually associated in the popular imagination with miniature paintings and carpets, the arts of the Qajar period are characterized by large-scale works and new technologies. (Apollo Magazine)

Elliott Arkin’s Quest to Counter Art World Elitism Culminated in a 10-Foot-Tall Picasso

Artist Elliott Arkin just spent roughly $120,000 of his own money producing a 10-foot-tall sculpture of Pablo Picasso pushing a lawn mower. (Artsy)

Getty Foundation Supports the CAA-Getty International Program for an Eighth Year

posted by CAA — June 05, 2018

The Getty Foundation has awarded CAA a grant to fund the CAA-Getty International Program for an eighth consecutive year. The Foundation’s support will enable CAA to bring twenty international visual-arts professionals to the 107th Annual Conference, taking place February 13-16, 2019 in New York City. Fifteen individuals will be first-time participants in the program and five will be alumni, returning to present papers during the conference. The CAA-Getty International Program provides funds for travel expenses, hotel accommodations, per diems, conference registrations, and one-year CAA memberships to art historians, artists who teach art history, and museum curators. The program will include a one-day preconference colloquium on international issues in art history on February 12, 2019, to be held at Parsons School of Design.

Read about deadlines and the application process for the 2019 CAA-Getty International Program.

The CAA-Getty International Program was established to increase international participation in CAA and the CAA Annual Conference. The program fosters collaborations between North American art historians and curators and their international colleagues, and introduces visual arts professionals to the unique environments and contexts of practices in different countries. Since the CAA-Getty International Program’s inception in 2012, 105 scholars have participated in CAA’s Annual Conference. Historically, the majority of international registrants at the conference have come from North America, the United Kingdom, and Western European countries. The CAA-Getty International Program has greatly diversified attendance, adding scholars from Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, Africa, Asia, Southeast Asia, Caribbean countries, and South America. The majority of the participants teach art history (or visual studies, art theory, or architectural history) at the university level; others are museum curators or researchers.

One measure of the program’s success is the remarkable number of international collaborations that have ensued, including an ongoing study of similarities and differences in the history of art among Eastern European countries and South Africa, attendance at other international conferences, publications in international journals, and participation in panels and sessions at subsequent CAA Annual Conferences. Former grant recipients have become ambassadors of CAA in their countries, sharing knowledge gained at the Annual Conference with their colleagues at home. The value of attending a CAA Annual Conference as a participant in the CAA-Getty International Program was succinctly summarized by alumnus Nazar Kozak, Senior Researcher, Department of Art Studies, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine: “To put it simply, I understood that I can become part of a global scholarly community. I felt like I belong here.”

An Interview with Roberto Tejada, CAA’s New Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion

posted by CAA — June 05, 2018

Roberto Tejada

Last week, Roberto Tejada, CAA’s newly elected vice president for diversity and inclusion, talked with Hunter O’Hanian, CAA’s executive director, about the state of the field and why achieving true diversity is so difficult in the arts field.

The interview accompanies CAA’s newly created Values Statement on Diversity and Inclusion, adopted by the CAA board of directors in May 2018.

Hunter O’Hanian: You were elected as CAA’s first vice president for diversity and inclusion last October. Can you tell me why that position was created and what you hope to accomplish?

Roberto Tejada: Let me answer that first with a confession. I joined CAA as an emerging professional many years ago, newly positioned in academia, but not altogether of academia. I’d spent a decade of my formal and informal working years in the art and literary worlds of 1990s Mexico City. When I returned to the US, there were few art history PhD programs with faculty specializing in Latin American and US Latinx art; the art-related disciplines were not especially open or inclusive, and the CAA and its conference consistently felt to me like alienating spaces. So I was never much engaged as a member.

A few years ago, in 2013-2014, I had the opportunity to be in attendance at a CAA retreat held at Clark Art Institute, where I was a fellow. I listened to CAA’s leadership in discussions that led to the drafting of its current strategic plan; and I was impressed with the various commitments among its stakeholders to issues of advocacy and questions of diversity and inclusion. Those conversations inspired me to consider it was possible to effect change from within, so I agreed to put myself forward and was elected by the board in 2016 to serve as Secretary.

My understanding was that CAA’s membership had long sought leadership, whether on the board or staff, to embody, energize, and encourage a commitment to diversity and inclusion at every level of the organization. Under review were resolutions that resulted from the perseverance of CAA’s Committee on Diversity Practices, other subcommittees, and the efforts of many individual members, including the “Resolution to Create a New Officer with the Title of Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion” and the “Resolution Adopting a Values Statement on Diversity and Inclusion.”

Why was the position was created? It’s no secret that the membership of scholarly associations is in decline and that cultural institutions more broadly jeopardize their relevance and sustainability when they fail to make diversity and inclusion central to an organization’s structuring values. For the last decades, cultural life and fields of study have been categorically redefined by the art and scholarship of underrepresented groups; by artists and intellectuals of color, LGBT scholars, and others who have faced the challenges of institutional spaces, often without networks of support.

Also, insofar as the language of diversity and inclusion readily serves the neoliberal agenda, it’s conveniently adopted and used by universities and other organizations as a cover for actual equity in terms of race, ethnicity, skin color, and other social markers of difference, visible and invisible. The promotion of diversity and inclusion involves redressing an entanglement of past narratives but with a steady eye on the present and future. One way to view it, appropriate to art and design, is as a work-in-progress. CAA has been watchful of currents in higher education and the arts and it has led advocacy efforts of great impact for diversity and inclusion. If equity and inclusion were to become the priority issue for CAA and its membership, the human and intellectual vibrancy of our respective institutions could begin to more accurately reflect the plural narratives that have led to the composition of contemporary society. I’m passionate about the role that the board and membership can play to empower others, and so change the faces of CAA.

But in the context of current political discourses in the government and media, the challenge of advancing equity in the arts and humanities is to move beyond the model of appealing to hearts and minds, and to encourage policy-change guidelines that are concrete channels to access.

HO: What particular issues do you see in the fields of art history and visual arts with regard to diversity, either in the academic world or museums? A high percentage of CAA’s members are white. Is there a reason for that?

RT: Despite the multicultural context of the so-called global turn, the fields of art history and the visual arts have not been particularly hospitable to persons deemed different. If you serve on enough admission and hiring committees at different kinds of institutions, you cannot ignore the implicit biases that continue to perpetuate a lack of equity. Although fields of research and curricula have adapted to account for plural histories, the bodies that make art and design, that care and write about practices, history, preservation, and display at universities and museums, are still overwhelmingly white. It’s challenging to recruit emerging professionals of color who feel underrepresented in CAA. Members within the organization, however, have effected change. For example, the US Latinx Art Forum (USLAF) is an affiliated society that was formed by CAA members, and it now includes around 300 artists, art historians, curators, and other art professionals. Its founders Adriana Zavala and Rose G. Salseda, responded to “ongoing marginalization of US Latinx art within the academy and specifically within both ‘American’ and ‘Latin American’ art history.” USLAF’s members advocate for scholarship at the intersections of Latinx, African-American, Asian-American and Indigenous art and art histories. Its efforts are positioned to inspire artists and scholars of color to join and participate in CAA.

HO: In May, the CAA board of directors passed its Values Statement on Diversity and Inclusion. Why this particular statement now?

RT: That statement was a collaborative effort that resulted from discussions first among members of the Committee for Diversity Practices; then among board members, who voted to pass the statement. The statement will strike many as belated. As a starting point, it has been retroactively amended to the Strategic Plan and will serve as a guiding frame of reference for all CAA initiatives and actions moving forward.

HO: What can practitioners/educators in the field do to help diversify their own departments or student cohorts?

RT: Flora Brooke Anthony, Chris Bennett, and Katherine Brion facilitated an excellent workshop at the last CAA Annual Conference in Los Angeles on the “disconnect between intention and practice” and on why faculty hiring guides and administrative initiatives have been unsuccessful at creating diverse departments. Some of the short answers have to do with the professional pipeline, implicit bias, the comfort zone idea of “best fit,” and the social factors to do with accumulation of advantage and disadvantage. The long view requires challenging our membership to lend efforts and energies in the service of inclusion that actually enhances one’s research imagination at the departmental level and in the classroom. There are resources on CAA’s website: standards and guidelines for diversity practices, links to a database on multicultural teaching, digital resources with classroom ideas, archives of digitized imagery, and bibliographies of global visual culture. There are ways that practitioners and educators in art and art history departments can partner with units and other departments on campus whose faculty and graduate student research addresses the scope of human diversity and the structures of exclusion or discrimination. Departments can explore the possibility of creating residency fellowship for recent MFAs or PhDs who bring different embodied experiences. There are CAA-sponsored web platforms to be explored that could serve to link emerging professionals and graduate student to create an open space for questions and concerns relevant to faculty of color in departments unfamiliar with diversity needs. Department can actively recruit from diverse universities and community colleges, with an openness to candidates with experiences and expertise not always associated with the arts.

It’s important to remember as well that students and professionals of color at different stages of a career path often complain that so-called target opportunities are experienced and perceived as marginalizing, empty appeals to special treatment that once again delegitimizes the actual merits and recognition of excellence among underrepresented future scholars, designers, artists, curators and other museum professionals.

HO: Do you see movements, changes and trends on the national level that is making diversity work easier or more difficult?

RT: I think there is enough evidence to discern that the rhetoric fueling racial fears and resentment against minorities, enabled nationally and internationally by those in power, is inclined to have ripple effects in academia and in the arts. It has entitled attitudes and actions that have made the need to advocate for diversity and inclusion all the more urgent.

For more on CAA’s advocacy efforts, click here.

Click here to access the CAA Arts and Humanities Advocacy Toolkit.

New in caa.reviews

posted by CAA — June 01, 2018

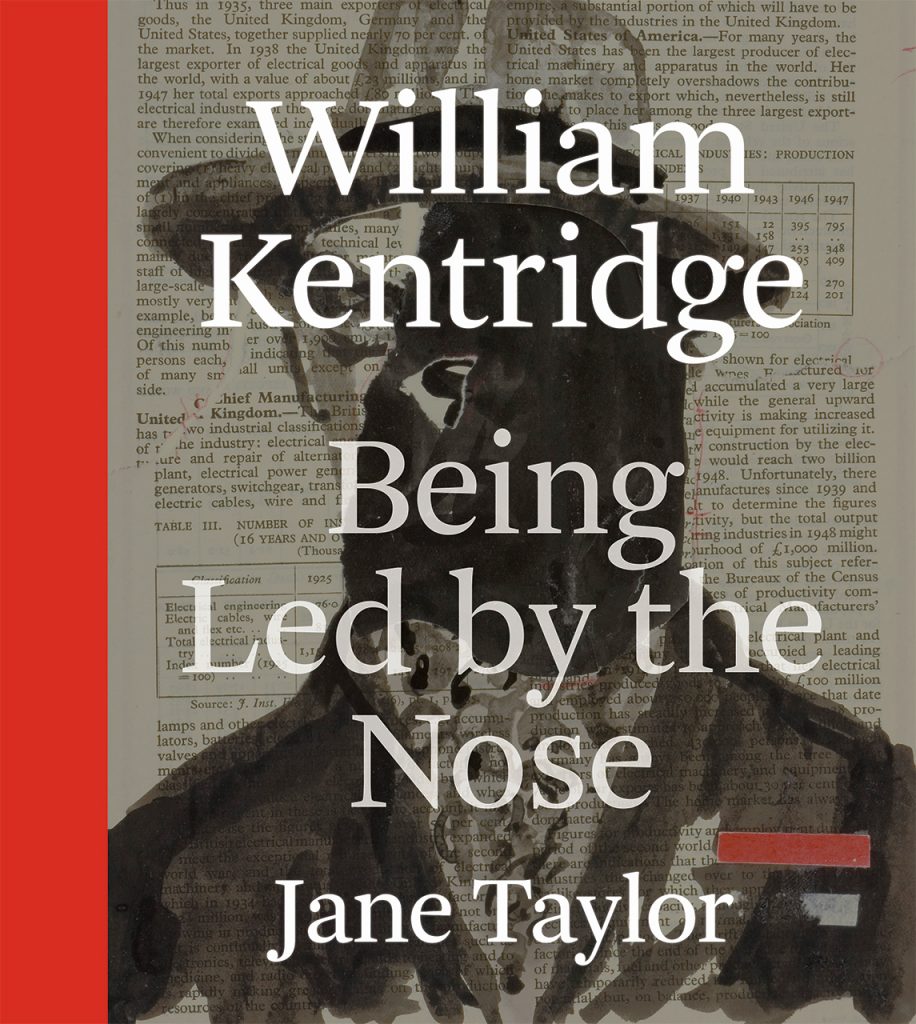

crystal am nelson writes about William Kentridge: Being Led by the Nose by Jane Taylor. Read the full review at caa.reviews.