CAA News Today

CAA Invites Proposals Related to Climate Crisis at 2021 Annual Conference

posted by CAA — February 26, 2020

Fridays For Future protest in Toronto, Canada. Photo: Jasmin Sessler

As part of the 2021 Annual Conference, CAA seeks to offer a selection of sessions, papers, speakers, and related programming on the topic of Climate Crisis. Including but going beyond eco-art and eco-criticism, and with climate justice and intersectional thinking as priorities, panels and presentations can address ecology as a matter of the content of artworks, but also, and pressingly, how we—artists, designers, and art historians, institutional stakeholders and independent practitioners, and members of allied fields—can and should change our professional practices in light of the crisis.

We invite discussions of creative interventions into the status quo, up to and including a serious discussion of ways of reducing the carbon footprint of the annual conference itself, while preserving and enhancing access. Practices and themes may include remediation and amelioration, thematic representation and critique, the ramifications of change for institutions and collections, issues of preservation, and the nature of research. We invite radical and practical proposals. The conference content will stress a broad and inclusive conversation on climate crisis impact through the lens of age; gender; nationality; race; religion; and socioeconomic status among others.

A Letter to CAA Members from the History of Art Department at Yale University

posted by CAA — February 03, 2020

Dear Fellow CAA Members,

Last week CAA forwarded to its members an article from a student newspaper, the Yale Daily News, on the subject of introductory courses in the History of Art at Yale, without opportunity for comment from the Department. In the statement below my colleagues and I explain what is actually happening, as we move to offer Yale undergraduates a range of introductory courses that do justice to the diversity of our faculty’s research, of Yale’s collections and of the student body itself.

I work with a group of brilliant art historians who are constantly rethinking what we teach and how to teach it – our vision is expansive rather than reductive, in terms both of coverage and of art-historical methodology. It’s an interesting reflection on the current media ecology that the modest, incremental and generous changes being introduced to Yale’s curriculum could lead to an astonishing outburst of reactionary moral outrage online. Hyperbolic comparisons are rife: the ‘New York Post’ sees us as Visigoths poised to destroy Rome. We read of ‘Stalin at Yale.’ But Stalin murdered nine million people, while our Department is offering four, rather than two, 100-level courses. The parallel is imprecise, to say the least.

As all of us, across the profession, are exploring how to move forward, inspiring students to study the history of art and architecture. This is a matter of urgency in a world where critical visual skills have never been more important. We assert for our discipline a central role in a liberal arts education. Accordingly, plans are already afoot for a discussion around introductory art history teaching at the New York meeting of the Association in 2021. Visigoths will be welcome. I hope to see you there!

- Tim Barringer, Chair, Department of the History of Art, Yale University

The following statement has been approved by all members of the History of Art Department at Yale University:

For more than half a century, Yale’s History of Art Department has been dedicated to “the study of all forms of art, architecture, and visual culture in their social and historical contexts.” A particular strength of the Department’s teaching is close engagement with the great works from major world traditions held in the Yale University Art Gallery, where spectacular examples of European and American paintings and sculpture, prints, drawings and photographs sit alongside world class collections of Asian, African and the Indo-Pacific art. The Beinecke Library, Yale Center for British Art and Peabody Museum hold manuscripts, paintings, drawings and artefacts central to our field of study and teaching mission.

Art history is a global discipline. Yale faculty have made field-changing contributions to the study the arts of the Americas (notably Pre-Columbian art and the full range of North American art from colonial to contemporary), African art and arts of the African Diaspora, Asian and Islamic Arts, and European art from ancient times to today. The diversity of the Department’s faculty and our intellectual interests finds an analogue in the diversity of today’s student body.

Discussions in the Department have focused on how to ensure that this diversity of research and resources can inform and energize our teaching. Offerings at the undergraduate level include upper-level lecture courses that address a full range of subjects (such as ‘Greek Art and Architecture’, ‘African Arts and Expressive Cultures’, ‘American Photojournalism’ and ‘Introduction to Contemporary Art’). Small intensive seminars are more focused still (such as ‘Surrealism,’ ‘Japanese Screens’, and ‘The Global Museum’). We aim for the widest possible selection of courses, balanced across time and region, while we maintain and cherish intensive coverage of western art, from classical Greece to medieval, Renaissance and Baroque, nineteenth-century, modern and contemporary.

But what about survey courses, which aim to introduce a large body of students from across Yale to the History of Art? We have traditionally offered two survey courses. The first discusses the ancient Middle East, Egypt, and pre-Renaissance European art (HSAR 112). The second covers European and American art from the Renaissance to the present (HSAR 115). New introductory courses have been added to these two offerings, such as ‘Global Decorative Arts,’ ‘Arts of the Silk Road,’ ‘Global Sacred Art’ and ‘The Politics of Representation.’ Faculty members have designed these introductory courses to engage the wealth of objects in Yale’s collections but also to move across traditions and periods.

Beginning this past Fall 2019, the Department committed to offering four different introductory courses each year. All of these courses, current or future, are designed to introduce the undergraduate with no prior experience of the History of Art to art historical looking and thinking. They also range broadly in terms of geography and chronology. Essential to this decision is the Department’s belief that no one survey course taught in the space of a semester could ever be comprehensive, and that no one survey course can be taken as the definitive survey of our discipline.

As we continue to renew our curriculum while preserving our commitment to introductory teaching of the broadest scope, new courses will replace HSAR112 and 115. Some will engage with the monuments and masterpieces of European and American art, some will introduce other world traditions, and some will be organized thematically offering comparative perspectives. As always, our introductory classes will bring Yale students face to face with works of art and material objects of great beauty and cultural value from across time and place.

We remain as committed as ever to “the study of all forms of art, architecture, and visual culture” and to sharing insights into works of art, from the Parthenon sculptures to Benin bronzes, from Renaissance Florence to Aztec sculpture, from the Taj Mahal to performance and digital art. As life becomes increasingly dominated by the visual, through screens and lenses, Art History’s focus on critical visual analysis has never been more relevant. Recent excitement on social media about Yale’s curriculum demonstrates just how significant and lively – even controversial – the study of Art History can, and should, be. We are delighted to welcome large numbers of students to Art History classes at Yale now and in the future.

Member Spotlight: Barbara Hoffman

posted by CAA — November 21, 2019

Up next in our Member Spotlight series, we are highlighting the work of Barbara Hoffman, founder and principal of The Hoffman Law Firm and a pioneer in the field of art law who served as CAA’s pro bono legal counsel for ten years. Joelle Te Paske, CAA’s media and content manager, spoke with Barbara over the phone to learn about her rich history with CAA. Read the interview, edited for length and clarity, below.

Image courtesy Barbara Hoffman.

Hi Barbara. I’m delighted to have the chance to speak with you. You are one of our esteemed lifetime members who has been a part of the organization in various capacities for more than 40 years. That’s incredible.

The pleasure is mine. I loved working with CAA during my tenure there.

Just looking over your bio on your website, I’m just amazed at how many different roles you’ve taken on over your career as an art lawyer. How did you first get involved with CAA?

I’ve always been interested in art, and I studied in Paris at the Académie Julian during my junior year when I majored in French and Art History. But I wasn’t very aware of the College Art Association.

After my studies, I was one of the early art lawyers. I had founded the Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts in the state of Washington, and continued to develop and write on the subject of art law, at a time when there were only a handful of people who were doing it.

Before then, I practiced civil rights law in New York. I’m from New York—I went to Columbia Law School—and was helping artists on the side when I was in my senior year. I volunteered as a lawyer for the first Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts in New York. I was then recruited to be a law professor in Seattle and I’d had so much fun with Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts that I thought I would join the Washington branch when I moved. When it didn’t exist, I ended up founding the statewide Washington Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts, and hosting an art law clinic at the law school.

Oh, interesting. So it started in New York and then you brought it over to the West Coast, in Washington.

Yes. Then eventually I moved back to New York and I joined the New York City Bar Art Law Committee. I was also Chair of the Public Art Subcommittee. We drafted a balanced, annotated model contract to be made available to artists and administrators. Percent for Art was just starting, and most artists and bureaucrats had little knowledge of copyright and other issues in public art.

The National Endowment for the Arts put together a task force of artists and administrators in which I was invited to participate, alongside Joyce Kozloff, who was on the CAA Board of Directors at the time. Susan Ball was executive director at the time. There was a feminist uprising, and my name was put forward to replace Gil Edelson.

I was CAA’s pro bono outside counsel and member of the executive committee for ten years. Among many activities, I wrote a column for CAA on legal issues. My fondest memories are those of working with the different CAA committees and their chairs. Particularly memorable was the work I did with Albert E. Elsen, a professor of art history and a great scholar on Rodin. We revised the guidelines for the code of ethics for art historians. And I worked with several well-known artists too, many of whom are no longer with us.

I also advised all the CAA publications. This was an interesting time for the issues of fair use and copyright in images. Through me, CAA got involved in what was called the Conference on Fair Use, taking place under the US Patent and Trademark Office and the US Copyright Office, which dealt with bringing copyright law into the digital world.

Before I came in to represent CAA, most of the people there were representing either libraries on one side, who were of course for fair use, or publishers, both trade book and academic publishers, who were of course for a stricter interpretation and enhanced copyright protection. But nobody was really talking about issues like images until we brought up to the subject.

On that issue I worked very hard, and CAA worked very hard. It was extremely controversial for the organization, because as you know, everybody at CAA wears multiple hats and the copyright issues involved both publishers and scholars. So I worked with the Copyright Committee and Fair Use and Christine L. Sundt, president of the Visual Resources Association and a member of CAA. She was a passionate devotee of legal issues there.

I imagine those are the fundamental building blocks for CAA’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use that was published in 2015.

There are earlier versions of it, too. There was one during my tenure and then it evolved over time. We were never successful in terms of getting the government, the Conference on Fair Use, to be able to come together to develop official guidelines. I spent hours and hours and hours developing scenarios. We tried to get people’s agreement on the analysis and whether it was or wasn’t fair use. But at the end there was never a resolution of that and I think it continued on until 2015. It was a long-going effort. We were the first people to really address the whole issue in the late eighties, early nineties.

That’s fascinating. And especially now, with the emergence of the internet.

Another thing that we were really involved with during my tenure was the issue of freedom of expression. I represented CAA and was active in what we now call the Culture Wars, when Jesse Helms tried to ban the publication of [Robert] Mapplethorpe’s images. This was in 1989, and continued through the 1990s.

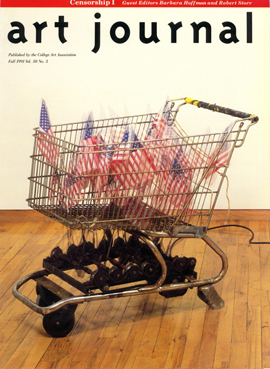

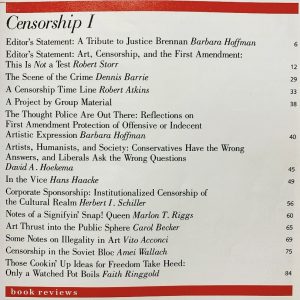

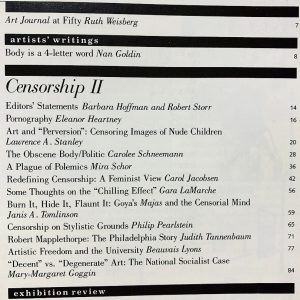

They were extremely active times. I’m most proud of the two-volume issue I did on censorship with Robert Storr for Art Journal. It was voted at the hundredth anniversary conference the best Art Journal that was published in the journal’s history.

To accompany this interview, we’ve brought the historic two-volume issue out from behind the paywall for readers to explore through the end of December 2019: Censorship I and Censorship II

For the double issue, I dedicated my statement to Justice Brennan of the Supreme Court. In my view, his decisions on the Supreme Court regarding the First Amendment and freedom of expression basically did more to provide contours of protection for artistic expression than any other Supreme Court Justice.

Then Rob Storr made his editor’s statement a full reprint of Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio. He got permission from the Mapplethorpe Foundation because of his connections to publish them, but when we sent it to our normal printer, they were afraid to publish it because they thought they (or CAA) would be sued for pornography. They asked us to find a different printer. So we sent it around to all these places that might publish pornography. But the pornography magazines that we sent them to didn’t have the quality that we would require for the CAA journals! So we went to The Burlington Magazine and asked them if they would print it. It was much more expensive, but our usual printer paid the difference. So it was actually printed, by my recollection, by The Burlington Magazine.

There were two fall outs from the issue. The first fall out was a number of CAA members dropped their membership. Pretty amazing. They said the issue should have come with a warning label. You know, they got it in the mail, they left it on the table, and then their children saw it, with no warning.

Another spin off was because the CAA journal goes to every single university that’s a member for the library and art departments, the images that people had been talking about—but never saw—were suddenly available. As part of this I ended up participating in a panel at the University of Nashville, defending a professor who had brought that issue to his class of drawing and photography.

It was all a very meaningful experience. As a result, I was involved in authoring two friends of the court briefs, in the district court and the appellate court, on behalf of the College Art Association. Those were then quoted by the court defending Karen Finley and what they called the NEA Four [Karen Finley, Tim Miller, John Fleck, and Holly Hughes], who had their NEA grants declined because of the Helms amendment. So we introduced a friend of the court brief on behalf of College Art Association, and another one was on behalf of College Art Association and PEN America.

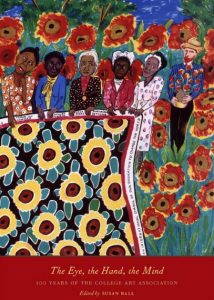

Later on, the organization’s centennial publication featured an image from Faith Ringgold’s French series that I licensed as her lawyer at the time. Faith was an active CAA member on the board and committee on diversity.

CAA’s centennial publication,The Eye, The Hand, the Mind: 100 Years of the College Art Association, with Faith Ringgold’s The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles (1996) on the cover.

The complexity of being an art lawyer—it brings you into so many different issues.

It was great. As I said, I worked with all the CAA Committees over that time. I still go to conferences from time to time and participate. And I just, you know, I’m happy to see so many artists that I’ve worked with being rewarded over time by the CAA. I’ve shown up for their presentations, the last ones being Howardena Pindell and Ursula von Rydingsvard for lifetime achievements.

Yes! Our 2019 honorees.

So I’m still keeping up and seeing how the organization has grown and changed. My legacy is these cases, my friends, and the guidelines. A wonderful opportunity for me to combine my passions—law and art history. As a member of the Executive Committee I attended all the CAA annual conferences, and when I wasn’t doing official business, I’d go to art history sessions. I have very happy memories of the wonderful people that I met there. I’m still in contact with many of them. That’s a part of my life that’s ongoing.

That’s wonderful.

And I’m still doing the same thing—still fighting for artists. Still fighting for the first amendment. Still doing public art. So, I feel very fortunate to be a life member.

Barbara Hoffman Biography

The Hoffman Law Firm continues as a preeminent global art and copyright boutique with a focus on Europe, Asia, Africa, and the United States. Author and editor of A Visual Artist’s Guide to Estate Planning (1996 and 2008), Barbara Hoffman also advises artists, galleries, and their estates on legacy planning, and endowed foundations.

Barbara has been recognized by her peers and clients with leadership posts and honor, including as Chair of the New York City Bar Association Committee on Art Law, Chair of the International Bar Association Committee on Art and Cultural Institutions and Heritage Law, and being selected to New York Super Lawyers, Best Lawyers in America, and Best Law Firms in art law and copyright law (2012-2020).

In addition to her service on the CAA executive committee, Barbara serves or has served on many boards, including ArtTable, Performa and the boards of several artists’ foundations. She was voted one of Art and Auction 51’s Power Women in the Art World 2016. www.hoffmanlaw.org

An Interview with Kellie Jones, 2020 CAA Distinguished Scholar

posted by CAA — October 28, 2019

We are delighted to welcome Dr. Kellie Jones, professor in Art History and Archaeology and the Institute for Research in African American Studies (IRAAS) at Columbia University, as the Distinguished Scholar for the 108th CAA Annual Conference in Chicago, February 12-15, 2020.

Dr. Jones, whose research interests include African American and African Diaspora artists, Latinx and Latin American Artists, and issues in contemporary art and museum theory, is the recipient of awards from the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Harvard University, Creative Capital, and Warhol Foundation, among others. In 2016, she was named a MacArthur Foundation Fellow. In 2018, Dr. Jones was the inaugural recipient of the Excellence in Diversity Award from CAA.

CAA media and content manager Joelle Te Paske spoke with Dr. Jones earlier this fall to learn about what she’s working on and looking forward to in upcoming exhibitions and scholarship. Read the interview below.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Dr. Kellie Jones. Photo: Rod McGaha

Hi, Professor Jones. Thank you for taking the time for this interview. It’s an honor to speak with you and we’re excited that you’ll be with us in Chicago.

I’m looking forward to it.

Great. So to begin—to locate ourselves in time and place—how are you? How was your summer?

It’s always fun, and it always ends too quickly. I think that’s just normal. [Laughs]

Yes, I guess that’s where we should be at this point [laughs]. Were you working on a particular project this summer?

Yes. I was working on a project for Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts (CASVA). Huey Copeland of Northwestern University and Steven Nelson of UCLA are spearheading a Black Modernisms seminar with a group of scholars. I just finished an essay on the Harlem Renaissance that is still to be titled. I haven’t written extensively on that period so I’m really looking forward to hearing back from them. It involves race and gender and I’m very excited about it.

What else is exciting in your work right now?

Candida Alvarez: Here, A Visual Reader (Green Lantern Press 2019), the first major monograph on the Chicago-based painter, is about to hit shops. I’m excited by this project to which I contributed the essay, “When Painting Stepped Out to Lunch.” I have book that I’m finishing on global conceptual art networks that is tentatively titled Art is an Excuse, on how conceptual art allowed for different types of global connections. One great example is Senga Nengudi and her relationship to Japan which is something I’ve written about earlier but I wanted to more forthrightly connect to Japanese conceptualism. So how does Senga Nengudi fit into that dialogue, or what is her dialogue? I’m thinking about conceptual art as a motor for global art connection, different from what people call globalization—more like artist dialogues, not neoliberal globalization.

A macro view.

The book is more about relationships. We always think about artists in their particular nationalist space. What did Japanese conceptualism look like? What did Latin American conceptualism look like? How were they different? But we really don’t talk about the kind of dialogue that people have with each other. That’s really the whole premise of the project.

That’s terrific. I read that for undergrad at Amherst College you made an interdisciplinary major. I was going to ask: Has an interdisciplinary outlook been formative in your career? But I feel you’re already embodying that.

You’re absolutely right. I created an interdisciplinary major at Amherst. Shout out to my alma mater and to liberal arts education.

We love that at CAA, yes.

And we love it because it allows people to see the breadth of the world in some fashion and then choose something or choose a few things. I’m one of the people that thought about Latin American and African American and Latinx artists at least from my college years, and I’ve been going with that for the longest, along with ideas of the African diaspora. You might start out with “Let’s compare”—the comparative structure; the binary is such a signature of art history. But then you realize that it’s so much more than a just a binary—the interdisciplinarity, the multidisciplinarity. That’s always been a part of what I’ve looked at because at that time—and I know I’ve said it on numerous occasions in numerous platforms—art history was really taught one way. Because I had grown up in New York I said, “But wait a minute, they’re leaving out all of these people that are making art that I know!” That I see every week. I mean, how is that possible? So I started there and just kept going.

I also read that you wanted to be a diplomat originally, and that makes sense to me. I think art historians are often part-diplomats, part-detectives, part-scientists. There’s so much that goes into the field.

Absolutely. I wanted to get away from art. I grew up with artists and poets and I said, “Oh my god, these people are broke. I can’t do that.”

Well, that’s realistic—I suppose it’s changed, too.

It’s absolutely changed, but if you’re thinking about late 1970s—wow. People weren’t even thinking about objects too much.

Someone reminded me much later—maybe a couple of years ago—they said, “Well you know, you’ve been doing [diplomacy] with art. You’ve been a cultural ambassador with this work, because you’ve done shows around the world.” Art history became, “Wow, you can do the same things.” You can study languages. You can travel. It did become a way you could do all those things, and then of course as you just mentioned, as a curator you are a diplomatic entity between artists and the institution.

As a liaison, definitely. It’s sensitive.

Right. Even as an academic, if you’re traveling around or if you’re representing a contemporary artist in your writing—how do you balance how the artist sees themselves with what you have to say? There’s always that.

I’m curious what you see as emerging trends in scholarship, especially in art history.

I think students and academics—particularly a new generation—don’t want traditional art history as we have known it. They want a more interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, global understanding of art in the world. Art history is not just Europe, and it’s not just the United States. And the art of the United States meaning not just New York!

I think the other really exciting arena is, of course, gender. Gender studies. Queer studies in art history. Trans studies. All those things really change how we understand the object, how we understand history, the histories that we look for. There’s a similarity to the discoveries that I made when I was a student in college about how art history at that time did not represent even the histories of African Americans who were in New York, for instance. United States art history is written from a New York-centric perspective. And at that time, you didn’t see too many women in it. You didn’t see too many African Americans or Latinx figures. So now that such subjects are more widely known the next step seems to be to ask,”What is a queer art history?” And some people have been doing this for a while: Jonathan Weinberg, James Smalls, Julia Bryan-Wilson has brought us into the present with some of these ideas, and C. Ondine Chavoya with his Axis Mundo, project. So all these ideas are becoming more visible and I think it’s really exciting.

That’s one of the reasons why I’ve been so keen on my Harlem Renaissance article. It started out in one way, and then it took me in another direction; it takes another look at objects that have been dismissed as not being relevant, and sees them through a different lens. It opens up other paths into these works that have been discarded. Or maybe not discarded, but put to the side. Let’s ask, “What’s going on with gender in these works?” What’s going on with queerness, and how do they signify to a Harlem Renaissance that is quite queer? It’s something people in literature have discovered, certainly in the African American context, and they’ve been talking about that for years. Art history has to catch up.

Yes, you feel a real energy in the field, a real hunger for it. With recent protests around Warren Kanders at the Whitney Museum, what are your views on that momentum? [Editor’s note: Since this conversation took place, Warren Kanders announced his resignation from the Whitney Museum board.]

Well, you know, there have always been protests at US museums as well as those around the world. So whether you are a curator or a director who bares the brunt of the protest, or you are an artist who withdraws, you’re part of history. Scholars down the road are going to say, “These people pulled out. These people wrote a letter. These were the curators. These were the board members.” So for me it’s just part of history, and it has ebbs and flows. There are a lot of things going on in this world that artists are addressing, that artists see. They do respond to the world in one way or another. You may not see it visibly, but it’s there.

I agree. I think putting new ideas in the world the way artists do is cultural change, and like you said—it’s interconnected. You can’t really have one without the other.

Yes. It’s part of a larger history.

When did you first join CAA? Do you have a favorite memory from a conference?

I had joined CAA by 1990, when I served as the co-chair of the programming at the Annual Meeting for the Studio or Artists’ sessions with Robert Storr. I’ve been on plenty of panels since then, but to be honored in this way is humbling and exciting. Even better, all of the respondents I asked to participate on the Distinguished Scholar panel said, “Yes! I’ll be a part of it.” So I’m thrilled about that. I’ve been at Columbia University about 13 years, and I remember when Rosalind Krauss was honored, and I participated in Richard J. Powell’s Distinguished Scholar panel. So to step into those shoes, it seems a bit surreal.

Thinking of Chicago in 2020—do you have a favorite art-related excursion there?

Well, the South Side Community Art Center is legendary. It’s one of the original community art centers from the New Deal era, and it’s still in existence. I would definitely say go to that. That’s my favorite.

I’m marking it down for myself. Are there exhibitions coming up this fall that you recommend?

Senga Nengudi at Lenbachhaus in Munich; Robert Colescott at the Contemporary Art Center in Cincinnati curated by Lowery Sims and Matthew Weseley; Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at Yale Center for British Art curated by Hilton Als; Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal…, his first major survey at the Portland Art Museum. Curator Meg Onli at ICA Philadelphia has done a trio of shows under the title Colored People Time. The final component Banal Presents will be on view through December 22, 2019.

Shows that are further out that I’m excited about are Prospect 5 in New Orleans (Fall 2020), curated by Naima Keith and Diana Nawi. The citywide triennial in New Orleans is just a great experience. Everyone should check it out. Thomas Lax’s exhibition on Just Above Midtown gallery, that generative space of 1970s and 1980s, and its founder Linda Goode Bryant, will be wonderful to see at MoMA in 2022.

There are so many great young curators out here. Rujeko Hockley, Erin Christovale, numerous others. Tiona Nekkia McClodden is an artist who’s been doing some great archival curatorial work. She had a show that was in response to the anniversary of Mapplethorpe’s The Perfect Moment that just closed. There are just so many great people out here doing some wonderful things, and a lot of wonderful younger artists. I’m excited by it. We started out by talking about multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity—young curators are invested in that idea as much as scholars.

Oh and one thing that I’m really looking forward to down the line is, of course, the reopening of the Studio Museum in Harlem. I cannot wait for that!

Yes! It’s a ways off but that’s an exciting one. Well, thank you Dr. Jones. I appreciate you taking the time, and it’s been a pleasure to speak with you.

Thanks for your questions, and again it’s really an honor to be a part of this whole thing. I still kind of can’t believe it. I guess I will in February when I step off that plane!

The Distinguished Scholar Session honoring Kellie Jones will take place Thursday, February 13, 2020, from 4-5:30 PM at the Hilton Chicago, Grand Ballroom.

Biography of Dr. Kellie Jones

Dr. Kellie Jones is a Professor in Art History and Archaeology and African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University. Her research interests include African American and African Diaspora artists, Latinx and Latin American Artists, and issues in contemporary art and museum theory.

Dr. Jones, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, has also received awards for her work from the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Harvard University and Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation. In 2016 she was named a MacArthur Foundation Fellow.

Dr. Jones’s writings have appeared in a multitude of exhibition catalogues and journals. She is the author of two books published by Duke University Press, EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (2011), and South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (2017), which received the Walter & Lillian Lowenfels Criticism Award from the American Book Award in 2018 and was named a Best Art Book of 2017 in The New York Times and a Best Book of 2017 in Artforum.

Dr. Jones has also worked as a curator for over three decades and has numerous major national and international exhibitions to her credit. Her exhibition “Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980,” at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, was named one of the best exhibitions of 2011 and 2012 by Artforum, and best thematic show nationally by the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). She was co-curator of “Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the 1960s” (Brooklyn Museum), named one the best exhibitions of 2014 by Artforum.

Now Accepting Applications for the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions

posted by CAA — October 22, 2019

In August 2018, we announced that CAA had received a major anonymous gift to fund travel for art history faculty and their students to special exhibitions related to their classwork. After a successful inaugural year, we’re pleased to now be accepting applications for the second grant cycle of the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions.

The fund is designed to award up to $10,000 to qualifying undergraduate and graduate art history classes to cover students’ and instructors’ costs (travel, accommodations, and admissions fees) associated with attending museum special exhibitions throughout the United States and worldwide. The purpose of the grants is to enhance students’ first-hand knowledge of original works of art.

Applications are due by January 15, 2020.

GUIDELINES

- These awards support student and instructor travel costs incurred while visiting museum special exhibitions in the United States and worldwide.

- Graduate and undergraduate art history classes are eligible to apply for funds to attend temporary museum exhibitions in the United States and other countries. Travel to see permanent collections is not eligible, nor would be performances and related ephemeral events. Exhibitions on any artist, period, or area of art history are eligible for funding.

- Awards are made directly to institutions whose institutional membership in CAA is in good standing.

- Applicant instructors must have individual membership in CAA and be in good standing.

- Funds may only be used to travel to exhibitions that correspond directly to the content of the class.

- The size of the class for which a grant may be awarded shall not be larger than fifteen (15) students.

- Awards may only be used for admission fees, travel and lodging expenses for the instructor and class members. Every attempt to attain group rates must be made.

Completed applications must include the following:

- Instructor’s curriculum vitae

- A course description and syllabus that identifies and explains the exhibition as part of the pedagogical aim of the course – Be sure to detail how the visit is integrated into the course (up to 500 words)

- An explanation of the instructor’s expertise in the subject matter of the exhibition (up to 250 words)

- A tentative itinerary of travel and lodging (up to 250 words)

- A budget detailing transportation and lodging expenses associated with traveling to and from the exhibition and lodging and admission costs, including an explanation of how any travel and accommodation funds in excess of the award will be raised

- A letter of support from the instructor’s department chair or dean

CRITERIA

- How well the exhibition fits within the pedagogical aim of the course.

- The scholarly merit of the exhibition.

- Financial need. Would the class not be able to visit the exhibition, otherwise?

AWARDS

Awards will not exceed $10,000 per class, per exhibition.

All travel must be completed between June 2020 – May 2021.

REPORTING

Awardees must submit a report of up to 1,000 words which explains in detail the benefits received and problems encountered in the course of travel to the exhibition for which support was received.

*Reports must be submitted to CAA no later than two months after the completion of travel.

ANNUAL CONFERENCE

Recipients of the award will be guaranteed a session at the subsequent CAA Annual Conference after their travel has ended. CAA will make the session available, but costs associated with attending the conference, including registration, membership, travel, and accommodation, will be the participants’ responsibility.

TIMELINE

The deadline for application materials is January 15.

Marking Indigenous Peoples’ Day with Art Journal

posted by CAA — October 14, 2019

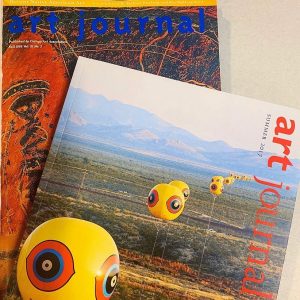

In celebration of Indigenous Peoples’ Day we have brought out from behind the paywall two issues of Art Journal in their entirety: our Summer 2017 issue on Indigenous Futures, (featuring Postcommodity’s Repellent Fence on the cover) and our Fall 1992 issue on Recent Native American Art. Articles from each will be open access until the end of October.

Announcing Notable Speakers for 2020 Annual Conference in Chicago

posted by CAA — October 01, 2019

We’re delighted to announce the following guests will be presenting at the 108th CAA Annual Conference, taking place February 12-15, 2020, at the Hilton Chicago.

Keynote Speaker

Amanda Williams. Photo: David Kasnic Photography

The Keynote Speaker for the 108th CAA Annual Conference will be Amanda Williams. A visual artist who trained as an architect, Williams’s creative practice navigates the space between art and architecture, through works that employ color as a way to highlight the political complexities of race, place and value in cities. Williams has received critical acclaim including being named a USA Ford Fellow and a Joan Mitchell Foundation grantee. Her works have been exhibited widely and are included in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She lives and works on the South Side of Chicago.

CAA Convocation featuring Amanda Williams’s keynote will take place Wednesday, February 12, 2020, from 6-7:30 PM at the Hilton Chicago, Grand Ballroom. Free and open to the public.

Distinguished Scholar

The Distinguished Scholar for the 108th CAA Annual Conference will be Dr. Kellie Jones, professor in Art History and Archaeology and African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University. Her research interests include African American and African Diaspora artists, Latinx and Latin American Artists, and issues in contemporary art and museum theory.

Dr. Kellie Jones. Photo: Rod McGaha

Dr. Jones, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, has also received awards for her work from the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Harvard University and Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation. In 2016 she was named a MacArthur Foundation Fellow.

Dr. Jones’s writings have appeared in a multitude of exhibition catalogues and journals. She is the author of two books published by Duke University Press, EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (2011), and South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (2017), which received the Walter & Lillian Lowenfels Criticism Award from the American Book Award in 2018 and was named a Best Art Book of 2017 in The New York Times and a Best Book of 2017 in Artforum.

Dr. Jones has also worked as a curator for over three decades and has numerous major national and international exhibitions to her credit. Her exhibition “Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980,” at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, was named one of the best exhibitions of 2011 and 2012 by Artforum, and best thematic show nationally by the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). She was co-curator of “Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the 1960s” (Brooklyn Museum), named one the best exhibitions of 2014 by Artforum. Read our interview with Kellie Jones.

The Distinguished Scholar Session will take place Thursday, February 13, 2020, from 4-5:30 PM at the Hilton Chicago, Grand Ballroom.

Distinguished Artist Interviews

The Distinguished Artist Interviews will feature artist Sheila Pepe interviewed by John Corso Esquivel, and artist Arnold J. Kemp interviewed by Huey Copeland.

Sheila Pepe. Photo: Rachel Stern

Sheila Pepe is a cross-disciplinary artist employing conceptualism, surrealism, and craft to address feminist and class issues. Hot Mess Formalism, Pepe’s most recent solo exhibition organized by the Phoenix Art Museum, traveled to the Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York; Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, Nebraska; and the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, Massachusetts between 2017 and 2019. A catalogue for the exhibition featured essays by by Julia Bryan-Wilson, Elizabeth Dunbar, Lia Gangitano, and curator Gilbert Vicario.

Other texts, all published in 2019, feature Pepe’s work: Vitamin T: Threads, and Textiles in Contemporary Art, the revised Art and Queer Culture by Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer, both published by Phaidon, and Feminist Subjectivities in Fiber Art and Craft: Shadows of Affect by John Corso Esquivel.

Venues for Pepe’s many other solo exhibitions include the Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, and the Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, North Carolina. Her work has been included in important group exhibitions, most recently Fiber: Sculpture 1960- Present, curated by Janelle Porter, organized by the ICA Boston; Queer Abstraction, curated by Jared Ladesema, organized by the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa and Even Thread Has Speech, curated by Shannon Stratton for the John Michael Kohler Art Center, Wisconsin.

John Corso Esquivel is the Doris and Paul Travis Associate Professor of Art History at Oakland University.

Arnold J. Kemp. Photo: Todd Rosenberg for the School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Arnold J. Kemp is an interdisciplinary artist living in Chicago. The recurrent theme in his drawings, photographs, sculptures and writing is the permeability of the border between self and the materials of one’s reality. Kemp’s works are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Studio Museum in Harlem, The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, The Portland Art Museum, The Schneider Museum of Art, and the Tacoma Art Museum. He has received awards from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the Joan Mitchell Foundation, The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and Portland Institute for Contemporary Art. His work has been exhibited recently in Chicago, Mexico City, New York, San Francisco and Portland. His work was also shown in Tag: Proposals On Queer Play and the Ways Forward at the ICA Philadelphia. Kemp was a founding curator at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts from 1993-2003 and is currently the Dean of Graduate Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Read our interview with Arnold J. Kemp.

Huey Copeland is Arthur Andersen Teaching and Research Professor, Interim Director of the Black Arts Initiative (2019-2020), Associate Professor of Art History, and affiliated faculty in the Critical Theory Cluster, the Department of African American Studies, the Department of Art Theory & Practice, the Department of Performance Studies, and the Gender and Sexuality Studies Program at Northwestern University.

The Distinguished Artist Interviews will take place Friday, February 14, 2019, from 4-6:30 PM at the Hilton Chicago, Grand Ballroom. Free and open to the public.

Announcing Research Travel Grants Funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art

posted by CAA — September 26, 2019

We’re pleased to announce our administration of the Terra Foundation for American Art Research Travel Grants.

Now administered and juried by CAA, the Terra Foundation initiated this grant program in 2003 to fund European candidates. It was expanded to reach candidates worldwide in 2012, and opened to US-based researchers in 2017 to travel abroad, developing American art scholar networks around the world with a total of 173 grantees since its inception.

The Research Travel Grants will be awarded annually, providing support to doctoral, postdoctoral, and senior scholars from both the US and outside the US for research topics dedicated to the art and visual culture of the United States prior to 1980.

“We are excited to expand our partnership with the Terra Foundation to provide continued support for scholars of American art,” said David Raizman, interim executive director of CAA. “Research funding for domestic and international scholars is essential to the vitality of the field, and these generous grants from the Terra Foundation will facilitate the advancement of their work. The inclusion of international scholars for these grants is especially gratifying, as it promotes new perspectives and engages the wider scholarly community.”

The grants foster firsthand engagement with American artworks and art-historical resources; build networks for non-US-based scholars studying American art; and expand access to artworks, scholarly materials, and communities for US-based scholars studying American art in an international context.

Awards of up to $9,000 will be granted on a per project basis by a jury formed by CAA. The first awards will be announced in March of 2020.

CAA’s administration of the Terra Foundation for American Art Research Travel Grants continues a long history at CAA of supporting travel and scholarship for professionals and students in the visual arts and design. Other grants offered by CAA include the Professional Development Fellowships for Graduate Students, the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Grant, the Wyeth Foundation for American Art Publication Grant, the Millard Meiss Publication Fund, the CAA Getty International Program, Travel Grants to the CAA Annual Conference, and introduced last year, the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions.

ABOUT THE TERRA FOUNDATION FOR AMERICAN ART

The Terra Foundation for American Art is dedicated to fostering exploration, understanding, and enjoyment of the visual arts of the United States for national and international audiences. Recognizing the importance of experiencing original works of art, the foundation provides opportunities for interaction and study, beginning with the presentation and growth of its own art collection in Chicago. To further cross-cultural dialogue on American art, the foundation supports and collaborates on innovative exhibitions, research, and educational programs. Implicit in such activities is the belief that art has the potential to both distinguish cultures and unite them.

Announcing New CAA Professional Committees

posted by CAA — August 08, 2019

CAA is pleased to announce the creation of two new professional committees: a Committee on Research and Scholarship, and a Services to Historians of Visual Arts Committee. The new committees were approved by the Board of Directors at their May 2019 meeting. Concurrent with our annual call for new committee members, we seek applicants to form the inaugural teams for these two new committees.

The deadline for these applications is October 1, 2019, for new committee service to begin at the Annual Conference in February 2020.

Discussion group at 2018 CAA Annual Conference. Photo: Rafael Cardenas

The formation of these new committees responds to requests from our membership and to a desire to be forward-looking in addressing the professional needs of our fields.

The Committee on Research and Scholarship will offer a resource to all members engaged in the production or consumption of scholarly research.

The Services to Historians of Visual Arts Committee will identify and address concerns facing the historian members of our organization (encompassing specialists in any facets of art, architecture, design, material culture, and visual culture).

The Services to Historians of Visual Arts Committee is intended to recognize our organization’s enduring support for historians, offering them a presence and a voice similar to the role played by other profession-specific committees in our organization (such as the Services to Artists Committee and the Committee on Design). As noted in the committee charge, the Services to Historians of Visual Arts Committee “offers a forum for the discussion of issues of mutual interest across the discipline’s many diverse fields and methodologies. In a climate of great threat to the survival of history of art and history of visual arts programs, this committee provides a locus for advocacy issues particular to historians in these areas of interest.” It is understood that the committee will play an active role in the Annual Conference but is also intended to serve as a central hub and resource for communication among historians of the visual arts well beyond the chronology of conference programming.

As stated in the committee charge, the Committee on Research and Scholarship is charged with “gathering information, [and] assessing and proposing organizational advocacy for CAA on matters concerning the research and scholarship in visual arts and design, encompassing all facets of research regarding history, theory, education and practice.” Specialists in the visual arts—whether practitioners or historians—face unique challenges in the production of their scholarship, such as the cost of image permissions, the closures or reorganization of academic presses, and/or the misalignment of the multiyear workflow of exhibitions or excavations against the strictures of a tenure clock. A scholar’s type of institutional affiliation, or independent scholar status, has an enduring impact on the types of research and scholarship that can be produced—arguably in more profound ways than in other humanities or arts fields. The Committee on Research and Scholarship will provide a vital hub to our members interested in addressing any of these areas of concern—or advancing other concerns or questions concerning the area of research and scholarship.

If you wish to apply for either of these new committees, send an email to Vanessa Jalet at vjalet@collegeart.org with a brief statement of interest and attach a reduced résumé (no more than 2-3 pages).

Kindly also enter in the subject line: “Applicant for Committee on Research and Scholarship” or “Applicant for Services to Historians of Visual Arts Committee”

Deadline: October 1, 2019

Committee on Research and Scholarship Charge

The Committee on Research and Scholarship is charged with gathering information, assessing trends, and proposing organizational advocacy for CAA on matters concerning the advancement of research and scholarship in visual arts and design, encompassing all facets of research regarding history, education, and practice. Recognizing that professionals must navigate a rapidly-transforming field of options for conducting research and disseminating the results thereof, the committee is responsible for assisting the organization in engaging with current issues and serving its membership in this important facet of their professional life.

Services to Historians of Visual Arts Committee Charge

The Services to Historians of Visual Arts Committee identifies and addresses concerns facing historians of art, architecture, design, material culture, and visual culture. It creates and implements programs and events at the conference and beyond. It offers a forum for the discussion of issues of mutual interest across the discipline’s many diverse fields and methodologies. In a climate of great threat to the survival of history of art and history of visual arts programs, this committee provides a locus for advocacy issues particular to historians in these areas of interest. The Committee lends support and mentorship for both seasoned and emerging professionals. It is also charged with maintaining dialogue with other professional organizations and affiliated societies focused on the history of art, architecture, design, material culture and visual culture.

An Interview with Amy Meyers, Recently Retired Director of the Yale Center for British Art

posted by CAA — July 26, 2019

In June, Amy Meyers ended a long and fruitful career as Director of the Yale Center for British Art, which she led for seventeen years. Prior to her appointment in 2002, she spent much of her career at research institutes including Dumbarton Oaks; the Center for Advanced Study in Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; and The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. She also taught at the California Institute of Technology, the University of Michigan, Mount Vernon College, and Yale, and has written extensively on the visual and material culture of natural history in the transatlantic world.

Joelle Te Paske, CAA Media and Content Manager, corresponded with Amy over email to reflect upon her tenure at the YCBA, her experiences with CAA, and her plans for the future. Read the interview below.

Amy Meyers, Yale Center for British Art, photo by Michael Marsland

Joelle Te Paske: Amy, thank you so much for speaking with us. To begin, what pathways led you to the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA)?

Amy Meyers: There is no question that my experiences as a graduate student at Yale set the stage for my return to direct the Yale Center for British Art 25 years following my arrival as a doctoral candidate in American Studies, in the fall of 1977—the first year the magnificent collections of the newly opened YCBA were accessible to students.

Long Gallery after reinstallation, Yale Center for British Art, photo by Richard Caspole

I had come to Yale to write a dissertation on the photographers who accompanied the federal geological surveys of the American West following the Civil War, and my interest in the art of empire brought me to explore the staggering collections of paintings, prints, drawings, maps, rare books, and manuscripts amassed by the Center’s founder, Paul Mellon, relating to the depiction of the natural world, particularly in the Americas.

John Ruskin, Study of an Oak Leaf, undated, pen and brown ink with watercolor over graphite heightened with gouache and gum; verso: graphite on paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The following spring, I enrolled in one of the first courses held at the Center—a seminar on Ruskin, taught by George Hersey. That course included students not only from the Department of the History of Art, but others, who, like me, were interested in the influence of Ruskin’s thought on many aspects of culture, particularly science. Professor Hersey’s important consideration of Ruskin as a major thinker of the nineteenth century, and the discussions that took place in that class between and amongst students, were foundational to my graduate education. I formed collegial friendships with many students who would go on to contribute significantly to art historical scholarship, both in academe and in museums, including David Curry, Bruce Robertson, George Shackelford, Mark Simpson, and Scott Wilcox—and these friendships have informed my scholarship and influenced the way in which I have approached the programs I have had the privilege to run, from the Virginia Steele Scott Gallery of American Art at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, to the YCBA.

The interdisciplinarity of Professor Hersey’s class reflected Yale’s commitment to exploration across disciplinary boundaries in many areas of study—a commitment that was unusual at American universities in the 1970s. Jules Prown, who had been the YCBA’s first director, creating the institution in concert with Paul Mellon and a distinguished committee of Yale faculty members, was himself devoted to examining the history of art from a broad range of vantage points, and he and his colleagues built that approach into the Center’s culture, both as a research institute and as a public museum with teaching at its heart.

Unidentified man, Paul Mellon, Kenneth Froeberg, and Jules Prown, during the construction of the Yale Center for British Art, 1974, photo by William B. Carter, Yale Department of Public Information, Institutional Archives, Yale Center for British Art

I was privileged not only to study with Jules, but to have him as one of my dissertation advisors. I learned from him the value of the close examination of objects as primary to art historical research, as well as the importance of working collaboratively with groups of scholars in developing the richest, most productive, and enjoyable of research communities. Jules drew around him, through his exciting classes and seminars, a large and devoted coterie of students from across the university who were interested in cross-cultural studies, including art history and material culture—a field he was instrumental in driving forward. Many of the students who took George Hersey’s seminar were part of this group; but others, including Margaretta Lovell (who by then was teaching a course on material culture with Jules), David Lubin, Angela Miller, Rodger Birt, Esther Thyssen, Buffy Easton, Valerie Steele, Catherine Lynn, Rebecca Zurier, Kenneth Haltman, Alexander Nemerov, Richard Powell, and Helen Cooper (who already was serving as Curator of American Paintings at the Yale University Art Gallery) also were active members of Jules’s circle of students (and there were many others who were off writing dissertations, such as Kathleen Foster, or who had graduated relatively recently and were known to us by their groundbreaking work, such as David Solkin). At that time, Bryan Wolf was a young professor of English literature and American Studies who had developed a strong interest in American art, and he also was an important member of Jules’s circle. I was tremendously privileged to have Bryan as one of my dissertation advisors, as well.

The sadly short-lived Center for the Study of American Art and Material Culture, directed by Richard Beard, was established by Robert McNeil, through the Barra Foundation, at the Yale University Art Gallery in the same year that the YCBA opened.

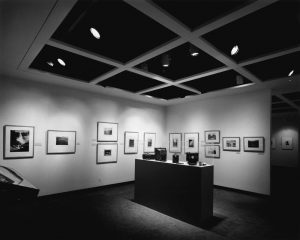

A Survey of American Photographs 1840–1940, installation as presented from March 28–June 6, 1978, organized by the Yale Center for American Art and Material Culture, photo courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery Institutional Archives

This center both reinforced the community of Americanists at Yale and gave me the opportunity to curate the first of my own exhibitions, American Photographs: 1840 to 1940. The group of Western American historians fostered by my third dissertation advisor, Howard Lamar, and Archibald Hanna, the then-curator of Western Americana at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, also promoted a culture of intellectual exchange, focused quite centrally on the visual culture of the West. Additionally, the American Studies Program offered students and faculty members with cross-disciplinary interests a supportive environment that encouraged innovative, experimental approaches to the study of American culture across the board. Collectively, these centers and programs taught graduate students of my generation at Yale the value of being a member of an engaging and supportive community of intellectual interchange, supported institutionally, and I have no doubt that this experience influenced my interest in being involved in study centers over the course of my professional career.

Indeed, as a graduate student, I was introduced to the vibrant culture of international research institutes when I was awarded a junior fellowship at Harvard University’s Washington-based research institute, Dumbarton Oaks (DO), my dissertation topic having shifted to a broader consideration of the relation of the visual arts to the natural sciences, from the colonial period, through the establishment of the republic, and into the nineteenth century. Some of my closest collegial friendships were formed in the community of DO, including my life-long professional partnership with Therese O’Malley, with whom I presently am organizing an exhibition on John and William Bartram and the emergence of environmental thought in America.

Therese O’Malley and Amy Meyers at a conference at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, 2005.

Therese and I were privileged to be hired by the first dean of the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts (CASVA), at the National Gallery, Henry Millon, to work as predoctoral research assistants for the Architectural Drawings Advisory Group, an international consortium convened at CASVA and supported by the J. Paul Getty Trust to set standards for the scholarly cataloguing of architectural drawings online. This early experience in working with an international group of scholars on one of the first electronic database projects in the history of art stimulated my life-long dedication to advancing the development of electronic tools for art historical research—one that I brought to the Yale Center for British Art when I became director.

The collective of fellowship programs in art history across the museums and research institutes of Washington, DC offered me a rich community of peers as an advanced graduate student and young professional, and this stimulating environment furthered my interest in working within the context of a study center, which had begun at Yale. The appeal of funding art historical research (and research in the humanities more generally) through grants and fellowships was strengthened by the work of my husband, Jack Meyers, an assistant director in the Research Division at NEH at that time—and we have been most fortunate to have developed comparable careers in this regard. While I worked for fourteen years as the Curator of the Virginia Steele Scott Gallery of American Art at the Huntington, which is one of the largest residential fellowship-granting research institutes in the humanities in the world, Jack served as a program officer and then deputy director of the Getty’s Grant Program (now Foundation). We both became fully committed to the support of scholarship internationally, and, over the last years, while I have served as director of the Yale Center for British Art, and CEO of the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (PMC) in London, Jack has served as President of the Rockefeller Archive Center. Our complementary positions have allowed us to share our experiences in the running of study centers, which has been wholly gratifying, and, I hope, of benefit to our mutual institutions.

JTP: What would you say are some of the biggest changes you’ve seen during your time at the YCBA?

AM: Certainly the greatest change I have seen in the field of British art over the last seventeen years, which has affected the YCBA and PMC in fundamental ways, and to a certain extent has been promoted by these sister institutions, has been a major shift in vantage point from what commonly has been called the “imperial gaze” to a more global viewpoint. Although by the time I was named director of the YCBA seventeen years ago, the approach to British art had become as much concerned with social history as with connoisseurship, works still were interpreted largely in terms of a relatively closed history of European art. The complex and tragic histories of the British Empire and slave trade were only beginning to affect the ways in which British art was understood, and the canon remained essentially defined as the creation of white, male artists of British birth—or, more generously, of white, male European or colonial American artists who came to practice in the British Isles, or who were associated with British artists and patrons on the Grand Tour.

Over the last years, a sea change has taken place, and not only has the canon expanded—and shifted—to include works by artists from many other parts of the world that came under British dominion or were deeply affected by the Empire, but also by artists of more diverse racial backgrounds and genders. The sense of the West’s ownership of the world on the part of historians of British art has been altered dramatically, and standard practice now insists that even the most traditionally canonical works must be reinterpreted from a global vantage point, and in terms of much larger and more challenging histories.

Art and Emancipation in Jamaica: Isaac Mendes Belisario and his Worlds, curated by Tim Barringer, Gillian Forrester, and Barbaro Martinez Ruiz, Yale Center for British Art, 2007, photo by Richard Caspole

JTP: What is a favorite memory—perhaps one that is less well-known—from your time there?

AM: My fond memories from my years at the YCBA—and the PMC—are innumerable, and it is extremely difficult to select a favorite. However, one program stands out as particularly memorable for me personally. In July of 2005, the YCBA co-organized a conference entitled, “Ways of Making and Knowing: The Material Culture of Empirical Knowledge,” with the PMC and the Wellcome Trust Center/Centre for the History of Medicine at University College London (UCL).

Pamela Smith, Harold Cook, and Amy Meyers, standing in front of a raised flower bed reconstructed from an eighteenth-century plan by garden historian Mark Laird, at Painshill Park, in Cobham, Surrey, during the final session of “Ways of Making and Knowing: The Material Culture of Empirical Knowledge,” July, 2005.

My co-conveners were close associates in the history of science: Pamela Smith, who is the Seth Low Professor of History at Columbia University, and Harold Cook, who, at that time, was director of the Wellcome Trust Center and now is the John F. Nickoll Professor History at Brown University. Beginning with a series of discussions at the Huntington, we planned an interdisciplinary conversation about the material construction of knowledge, examining how artisans and other makers of things informed the ways in which the natural world came to be understood in the West, from the sixteenth-century through the nineteenth. Exploring the relationship between two spheres traditionally understood to be distinct—practical and theoretical knowledge, the lectures and demonstrations were given by the seventy presenters, including art historians and historians of material culture, historians of science, artists, and craftspeople.

The program took place over five days, at sites across London ranging from the Chelsea Physic Garden, the Enlightenment Gallery at the British Museum, the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, the Natural History Museum, the Linnean Society, the V&A, and Painshill Park, in Surrey. This experimental program included as many object-study sessions and hands-on making workshops as formal papers, interrogating how the use of natural materials in the processes of making yielded the most profound understanding of nature, feeding science as much as technical knowledge in exciting new ways. A selection of the papers appeared under the title of the conference, in the Bard Graduate Center’s series Cultural Histories of the Material World, published by the University of Michigan Press in 2014. I must say that the support of Brian Allen, at that time the splendid and long-serving Director of Studies of the PMC with whom I had the honor of working closely for ten years, was a special pleasure.

Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte, and the Shaping of the Modern World installation, including Yinka Shonibare CBE’s Mrs Pinckney and the Emancipated Birds of South Carolina (2017), Yale Center for British Art, photo by Richard Caspole

I also remember with great fondness working with Joanna Marschner, Senior Curator at Kensington Palace, on Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte, and the Shaping of the Modern World, an exhibition co-organized by the YCBA and Historic Royal Palaces, with the support of the PMC, that was mounted in New Haven and London in 2017. Our mutual interest in women and patronage, particularly in relation to the natural sciences, found its expression in this project, and we look forward to working together on the subject long into the future.

JTP: What is a resource at the YCBA that you think people don’t often know about, but should?

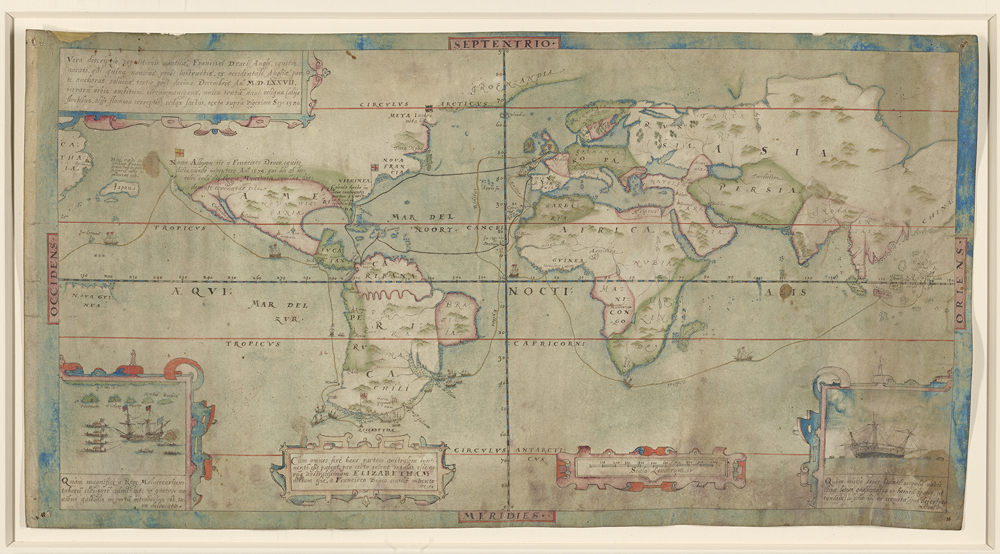

AM: The collection of British art at the YCBA is renowned as the largest and finest outside the UK, comprising over 2,000 paintings; 20,000 drawings and watercolors; 45,000 prints and photographs; and several hundred pieces of sculpture. Much less well known is the institution’s truly glorious rare book and manuscript collection. The Center’s founder, Paul Mellon, began his life as a collector in this field, and over his lifetime he amassed one of the greatest collections formed in the twentieth century, comprising approximately 35,000 titles. Mr. Mellon focused in part on British illustrated books, acquiring the renowned J.R. Abbey collection of British color plate books, which serves as the touchstone for all other collections of this kind. Other major parts of the collection include drawing manuals, sporting books and manuscripts, early maps and atlases, early printed books by Caxton and his contemporaries, and archival and manuscript material relating to British artists, writers, and travelers of all periods.

A True Description of the Naval Exploration of Francis Drake, Englishman & Knight, Who With Five Ships Departed from the Western Part of England on 13 December 1577, Circumnavigated the Globe and Returned on 26 September 1580 with One Ship Remaining, the Others Having been Destroyed by Waves or fire, [London (?), ca. 1587], pen and ink and watercolor on parchment, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The Rare Books and Manuscripts collection contains splendid photographic holdings, beginning with some of the earliest printed books including original photographic illustrations produced by the first British experimenters with paper-print photography, such as William Henry Fox Talbot. These collections have grown enormously over the years, as have the photographic collections in the Prints and Drawings Department, making the Center one of the most significant repositories of British photographs in the country.

The same holds true for the development of the institution’s collection of contemporary British art, and over the course of this summer, the Center has mounted an exhibition illuminating the role that donors have played in enhancing both areas of the institution’s collections over the last few years. Entitled Photographs/Contemporary Art: Recent Gifts and Acquisitions, the exhibition demonstrates the breadth and depth of these holdings and signals their continued growth.

Photographs | Contemporary Art: Recent Gifts and Acquisitions installation, Yale Center for British Art, photo by Richard Caspole

JTP: When did you first become a CAA member? Do you have a favorite memory from a CAA conference?

AM: I have been a member of the CAA for so long that I do not remember precisely when I joined—undoubtedly by the early 1980s, when I was attending conferences regularly in my later years of graduate school. My memories of the very first conference I attended are shrouded in the mists of time, but I believe that I joined a group of Yale graduate students at a conference in New York while I was still enrolled in courses, in the late 1970s.

I have countless happy memories from conferences throughout the years, from sessions I have co-organized on the visual and material culture of natural history with my long-standing colleague, Therese O’Malley, to the multitude of fine papers given by scholars in my own fields of American and British art. Of course, one of the most important functions of the conference is to introduce participants to subjects that lie beyond their own areas of expertise, and I have learned an enormous amount from papers on topics to which I have had little exposure, especially as art history has evolved in such exciting ways over the last years. New methodological approaches are always stimulating to consider, and I particularly have enjoyed learning from the work of younger colleagues. Indeed, the call for papers for next year’s conference promises a rich and important group of sessions that will have me running from one talk to the next throughout the proceedings.

Since 1989, due to my association with The Huntington and the YCBA and PMC, I have had the pleasure of attending the winter meeting of the Association of Research Institutes in Art History (ARIAH), as an affiliated society, which always is held the first day of the CAA conference. Naturally, I also have enjoyed attending reunions of the departments and study centers with which I have been connected. The joint reunion of the YCBA and PMC has been a true pleasure to co-host with the PMC’s current Director of Studies, Mark Hallett, who promotes the mutual interests of his London research center and the YCBA with dedication and inspired vision. Mark and I have been deeply grateful to the Deputy Directors of Research of these sister institutions, Martina Droth and Sarah Turner, for organizing these shared events annually.

I do have one favorite memory that stands out among all others, however, and that is of the 2009 Terra Foundation for the Arts Distinguished Scholar Session, entitled “Generations: Art, Ideas, and Change,” in honor of Jules Prown. Chaired by Bryan Wolf, and including papers by Alex Nemerov, Margaretta Lovell, Jennifer Roberts, Jennifer Greenhill, and Ethan Lasser, the session paid special tribute not only to the professor who had inspired so many of us as graduate students at Yale, but also to the scholar who had informed the work of students pursuing the study of American art and material culture throughout the world through his groundbreaking research and approaches to analysis.

JTP: I imagine it is impossible to summarize the sentiments surrounding a 17-year tenure, but if there was one feeling you could share in the wake of your departure from the directorship of the YCBA, what would you say it is?

AM: The feeling I wish to share is one of excitement.

Courtney J. Martin, photo by Argenis Apolinario

As I have indicated, the field of British art–and of art history more generally—is developing and changing in such important ways, and I have no doubt that Courtney J. Martin, who just has begun her first term as the Center’s brilliant new director, will work with her YCBA colleagues not only to continue to introduce the work of new artists to the collection, but to encourage an ever-expanding community of visitors from the university, the city, the region, and the world through innovative displays, exhibitions, publications, and programs. She is a tremendous addition to the impressive complement of collection directors under the excellent leadership of Yale’s Vice Provost for Collections and Scholarly Communications, Susan Gibbons, and I expect that splendid developments are about to take place across all of the university’s museums and libraries with this gifted team in place.

JTP: What are you most proud of having accomplished at YBCA?

AM: My pride lies in what I was able to accomplish in concert with my superlative friends and colleagues: the staff of the YCBA and PMC, Yale students and faculty members, the 250 visiting scholars who have joined our community to pursue research in the YCBA’s collections, our advisory committees and consultants, the PMC’s Board of Governors, and supporters of both institutions. So much has been accomplished collectively that a full review would be impossible, but I will outline some of our most significant collaborative achievements.

Working with museums and cultural institutions across the UK, and in certain instances the United States, we developed a program of over fifty major loan exhibitions which explored a wide range of topics from the early modern period through the current day. These were underpinned by workshops involving students and scholars from around the world, and they were enhanced by an equivalent number of significant publications produced in association with Yale University Press London (YUPL). Approximately forty in-house exhibitions and displays, often developed with undergraduates and graduate students, enriched the exhibition program, examining the Center’s own holdings from important new vantage points.

One such exhibition, Unto This Last: Two Hundred Years of John Ruskin, curated by three of Tim Barringer’s graduate students—Tara Contractor, Victoria Hepburn, and Judith Stapleton—has been in the planning stages for some time as the Center’s central contribution to the bicentennial commemoration of Ruskin’s birth (both critical and celebratory), and it will open on the evening of September 17th of this year, accompanied by a leading-edge catalogue edited by Tim, to which the students, and others, have contributed. I have no doubt that for this cohort of students, the experience of working with Tim on an assessment of Ruskin’s significance as a thinker for the modern world will be as important as George Hersey’s Ruskin seminar was for me and my own group of peers over forty years ago.

During the last seventeen years, the research cultures of the YCBA and the PMC were augmented through the joint efforts of a new Research Division at the Yale Center and an amplified program at the London Centre, which also produced a superb run of publications with YUPL. Support of scholars across the field of British art was substantially increased through the PMC’s grant program and the YCBA’s visiting scholars program. The PMC and YCBA also collaborated to develop an innovative online journal, British Art Studies, which is fully accessible, free of charge, to the world.