CAA News Today

In Memoriam: Richard Brettell

posted by CAA — August 11, 2020

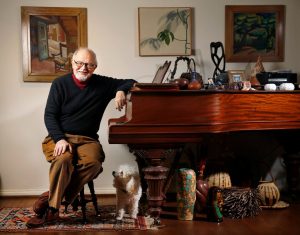

Dr. Richard (Rick) Brettell.

We were saddened to learn of the passing of longtime CAA member Dr. Richard Brettell last month at the age of 71. Dr. Brettell was a tireless advocate for the arts, a well-respected scholar, former director of the Dallas Museum of Art, and founding director of the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History at the University of Texas, Dallas. Read an remembrance by Jonathan D. Katz, Interim Director, Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies and Associate Professor of Practice in the History of Art at the University of Pennsylvania, below.

In Memoriam

Richard (Rick) Brettell died July 24, 2020 in Dallas after a long battle with prostate cancer—and entirely characteristically, he was working until the very end. A tireless advocate for the arts in general, for French Impressionism in particular and for Texas artists and the local cultural scene, Brettell spanned genres, chronologies, nationalities and professions with an acrobatic grace. He was a world class scholar, a museum director and builder, and above all a connector, of people to ideas, of money to institutions, of museums in France to museums in the US, of friends to other friends. Seemingly limitless in his capacity to extend friendship and take it up again, I’m sure there are legions out there who think Rick was their best friend. A man of sure and independent judgment, Brettell was as thrilled to bring attention to an underknown or even unsung artist as he was to Gauguin, and approached both with the same profound curiosity and boosterism.

A graduate of Yale University, Brettell’s dissertation on Pissarro set the pattern for the rest of his life. Once he became interested in something, he would not only write about it, he’d also work up an exhibition spotlighting it—in this case, the very first international Pissarro exhibition, curated when he was still quite young. He turned his enthusiasms into scholarship with a speed and assurance that suggested he saw no difference between the two modes. And the goal was always the same, to kindle the viewer’s own enthusiasm, to seduce close looking and careful thought and make art history, art criticism, and art appreciation one and the same.

Initially hired as a professor at the University of Texas, in 1980 Brettell left Texas to become the Searle Curator of European Painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. Renovating and reinstalling the Art Institute’s vast European art collection hardly impeded the string of notable international exhibitions he curated, most centrally the one that earned him the honor of being named a Chevalier (Arts et Lettres) by the French government: A Day in the Country, Impressionism and the French Landscape. Because Brettell traveled in some of the most rarified circles in the country, his genuine friendships with some of the country’s wealthiest citizens made him a rainmaker in a class by himself. When he was a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago and I was still a grad student, I remember visiting him at the museum to ask about the whereabouts of a specific Gauguin painting, the subject of a paper I was assigned. Rick reached down to the safe at his feet, opened it, pulled it out and nonchalantly asked, “this one?”

In 1988, Brettell moved to Dallas to become the McDermott Director of the Dallas Museum of Art. There he continued to develop important international exhibitions—including a new emphasis on the arts of Latin America and Africa—while also raising the funds to build a major new wing. In 1998, Brettell became the Margaret McDermott Distinguished Chair in Art and Aesthetic Studies at the University of Texas, Dallas (UTD). He would soon transform UTD, bringing in such transformational gifts as a huge endowment to build the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History. With the assistance of Margaret McDermott, in 2017 Brettell created a $150,000 bi-annual lifetime achievement in the arts award, The Richard Brettell Award in the Arts. The following year, he acquired the Barrett collection of Swiss art for UTD, consisting of 400 works, including a large percentage by the Swiss 19th/early 20th-century master Ferdinand Hodler. And last year, he helped UTD acquire the extensive Crow Collection of Asian Art, along with 23 million dollars to build a new museum, the second for the collection, on campus. A lifelong student of architecture, he helped to found the Dallas Architecture Forum. Many doubtless fondly remember his loud, enthusiastic, no holds barred architecture tours, where he would alternately vigorously praise and vehemently excoriate architects, and the houses and institutions they built.

Brettell was the author of numerous books and catalogs, including the editor of the forthcoming Gauguin catalogue raisonné. As a leading international specialist in French art history, he joined forces with his friend Elizabeth Rohatyn, then the wife of the Ambassador to France under Clinton, and Françoise Cachin, former Director of the French National Museums, to found an organization called FRAME (French/Regional/American Museum Exchange). He directed this project in cultural diplomacy bringing together twelve French and twelve American museums to cooperatively share works and develop exhibitions. For this effort, he was named a Commandeur in the French Order of Arts et Lettres. For decades, Brettell was loyally assisted by Pierrette Lacour, who shared his grand visions, but was rather more attentive to the nuts and bolts work of bringing them about.

Immensely erudite, opinionated, and frank, Brettell would assert that fame was no barometer of quality. He loved complicated, intelligent work regardless of the artist’s standing. He boosted Texas artists in general, and none more so than James Magee, an artist he frequently called the most underrated in the country. He was central to the ongoing effort to protect Magee’s extraordinary project in the desert outside of El Paso, The Hill, a hand-built mytho-poetic compound that has taken the bulk of Magee’s artistic life.

A famous raconteur, fabulous cook, witty tour guide, emotional lover of beauty and gossip, Brettell was roundly adored. He leaves behind his wife Caroline, his 94 year-old mother, his assistant Pierrette, and legions on every continent who basked, however briefly, in the warmth of his attention. A celebration of his life will be held at a later date. But those who wish to remember Brettell are encouraged to make donations to the University of Texas at Dallas’ Richard Robson Brettell Reading Room in the future UTD Athenaeum, which Brettell helped conceive.

Remembrance by Jonathan D. Katz.

You’re Invited: Envisioning the Future of Higher Education in the Arts

posted by CAA — August 03, 2020

Tuesday, August 18, 2020

2 PM – 3:15 PM (ET)

RSVP HERE

Hosted by Art World Conference

Facilitator: Natalia Nakazawa, Artist, Arts Administrator, and Educator

Participants: Deborah Obalil, President and Executive Director of AICAD; Meme Omogbai, Executive Director and CEO of CAA

In 2020, colleges and universities across the world have rushed to adapt to a new reality that questions the very nature of their work: a pandemic sent students home and protests shone a spotlight on inequality supported by many of our institutions, including those in higher education. Since March, everyone involved in education has had to rethink fundamentals and challenge core assumptions ranging from the format of instruction to what and who creates value. Since arts education is historically vulnerable to funding cuts and much of the instruction relies on hands-on studio classes, specialized equipment, in-person mentorship, and tuition dollars, the systemic changes necessary to thrive require radical, ethical thinking. What are the responsibilities and priorities being considered going into this exceptional academic year?

Artist and educator Natalia Nakazawa will facilitate a discussion between two important leaders in arts education: Deborah Obalil, the President and Executive Director of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design (AICAD), and Meme Omogbai, the Executive Director and CEO of the College Art Association (CAA). Both institutions support and advocate for artists, arts workers, and scholars in the art and design fields. Together, they will discuss the evolving paths forward for higher education in the arts, including structural changes and very significant challenges. What is the role of higher education in times of crisis? Since creativity is nurtured by the institutions they oversee, what are the creative solutions being implemented to address health concerns, anti-racism efforts, adjunct culture, and affordability? What are their hopes and expectations for the future?

This 75-minute webinar is designed with everyone in the art world from current students to artists, arts administrators, and art historians in mind. Questions submitted during registration will be incorporated into the discussion as appropriate.

PARTICIPANT BIOGRAPHIES

Natalia Nakazawa is a Queens-based interdisciplinary artist working across the mediums of painting, textiles, and social practice. Utilizing strategies drawn from a range of experiences in the fields of education, arts administration, and community activism, Nakazawa negotiates spaces between institutions and individuals, often inviting participation and collective imagining. She has held the position of Assistant Director of EFA Studios for over 8 years, supporting a large network of contemporary artists through subsidized studio spaces and professional practice opportunities in midtown Manhattan. Nakazawa received her MFA in studio practice from California College of the Arts, a MSEd from Queens College, and a BFA in painting from the Rhode Island School of Design. Her work has recently been exhibited at Wave Hill (Bronx, NY), Arlington Arts Center (Washington, DC), Transmitter Gallery (Brooklyn, NY), Wassaic Project (Wassaic, NY), The Old Stone House in Brooklyn (Brooklyn, NY), and The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY). Nakazawa has been an artist-in-residence at MASS MoCA, SPACE on Ryder Farm, The Children’s Museum of Manhattan, and Wassaic Project. She teaches at CUNY.

Deborah Obalil has over twenty years experience as a leader in the national arts and culture industry. She was appointed the Executive Director of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art & Design (AICAD) in June 2012, and then President in the fall 2015. Prior to her appointment with AICAD, Obalil operated a successful boutique arts management consulting firm, Obalil & Associates for four years. The firm provided consultation and facilitation in strategic business planning, marketing research and planning, and board development for non-profit arts organizations, independent artists of all disciplines, and creative for-profit ventures. Obalil has also served as Executive Director of the Alliance of Artists Communities and Director of Arts Marketing Center & Research at the Arts & Business Council of Chicago.

Meme Omogbai is Executive Director and CEO of College Art Association (CAA), the preeminent international support organization for professionals in the visual arts. Before joining CAA, Omogbai served as a member and past Board Chair of the New Jersey Historic Trust, one of four landmark entities dedicated to preservation of the state’s historic and cultural heritage and Montclair State University’s Advisory Board. Named one of 25 Influential Black Women in Business by The Network Journal, Meme has over 25 years of experience in corporate, government, higher education, and museum sectors. As the first American of African descent to chair the American Alliance of Museums, Omogbai led an initiative to rebrand the AAM as a global, inclusive alliance. While COO and Trustee, she spearheaded a major transformation in operating performance at the Newark Museum. During her time as Deputy Assistant Chancellor of New Jersey’s Department of Higher Education, Omogbai received Legislative acknowledgement and was recognized with the New Jersey Meritorious Service Award for her work on college affordability initiatives for families. Omogbai received her MBA from Rutgers University and holds a CPA. She did post-graduate work at Harvard University’s Executive Management Program and has earned the designation of Chartered Global Management Accountant. She studied global museum executive leadership at the J. Paul Getty Trust Museum Leadership Institute, where she also served on the faculty.

Explore RAAMP’s Resources on the CAA Website

posted by CAA — July 30, 2020

RAAMP (Resources for Academic Art Museum Professionals) has a new home! Moving forward, you can find all the resources you know and love here on our website at: collegeart.org/raamp

A project of CAA with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, RAAMP aims to strengthen the educational mission of academic museums and their parent organizations by providing a publicly accessible repository of resources, online forums, and relevant news and information. RAAMP’s coffee gatherings and video practica cover a wide variety of topics including advocacy, engagement, curricula building, cross-disciplinary collaboration, technology, development, and censorship.

To receive updates and invitations to upcoming RAAMP programming, sign up for the RAAMP mailing list.

For any questions regarding the RAAMP program, please contact Cali Buckley, grants and special programs manager, at: cbuckley@collegeart.org

RAAMP Coffee Gathering: Participatory Conversation on Reimagining Engagement in Academic Art Museums

posted by CAA — July 09, 2020

Coffee Gathering: Reimagining Engagement in Academic Art Museums

|

|

RAAMP Coffee Gatherings are monthly virtual chats aimed at giving participants an opportunity to informally discuss a topic that relates to their work as academic art museum professionals. Learn more here.

Submit to RAAMP

RAAMP (Resources for Academic Art Museum Professionals) aims to strengthen the educational mission of academic art museums by providing a publicly accessible repository of resources, online forums, and relevant news and information. Visit RAAMP to discover the newest resources and contribute.

RAAMP is a project of CAA with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

RAAMP Coffee Gathering: Gender Equity in the Museum (and Arts) Workplace

posted by CAA — June 30, 2020

Coffee Gathering: Gender Equity in the Museum (and Arts) Workplace

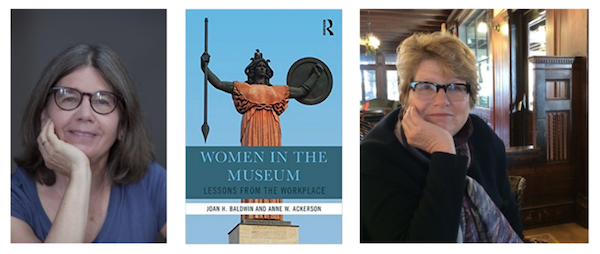

On Thursday, July 2 at 2:00 PM (EST) we will speak with Anne Ackerson and Joan Baldwin on gender equity in museums and workplaces.

To RSVP to this Coffee Gathering, please fill out this form.

A former museum director, Joan H. Baldwin is the Curator of Special Collections at The Hotchkiss School. She is the principal writer for the Leadership Matters blog which had 55,000 views in 2018. Her work has also appeared in The Museum Blog Book, “History News,” and “Museum” Magazine, Museopunks, and “The Guardian.” She is a co-founder of the Gender Equity in Museums Movement, and teaches in the Johns Hopkins University museum studies program. With Anne Ackerson, she is the co-author of Leadership Matters (2013) and Women in the Museum: Lessons from the Field (2017). She and Ackerson published a revision of Leadership Matters: Leading Museums in an Age of Discord in August 2019.

Anne W. Ackerson is a former history museum director, director of the Museum Association of New York, and director of the national Council of State Archivists. She is currently an independent consultant to cultural and educational nonprofits, specializing in leadership, governance, and management issues. With Joan H. Baldwin, she is the co-author of Leadership Matters, a book examining history museum leadership for the 21st century, and Women in the Museum: Lessons from the Workplace. She is a co-founder of the Gender Equity in Museums Movement (GEMM), which is focusing its recent efforts on education, advocacy, and policy development around pay equity, salary transparency, and sexual harassment in the museum workplace. In 2018, she and Baldwin spearheaded research, revealing that 62% of the museum workforce are affected by some form of gender discrimination. In addition to research and writing about gender inequity, she and Baldwin have presented their findings to the Texas and Pennsylvania Associations of Museums as conference keynoters and via their blog, Leadership Matters.

RAAMP Coffee Gatherings are monthly virtual chats aimed at giving participants an opportunity to informally discuss a topic that relates to their work as academic art museum professionals. Learn more here.

Submit to RAAMP

RAAMP (Resources for Academic Art Museum Professionals) aims to strengthen the educational mission of academic art museums by providing a publicly accessible repository of resources, online forums, and relevant news and information. Visit RAAMP to discover the newest resources and contribute.

RAAMP is a project of CAA with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

In Memoriam: Cynthia Navaretta

posted by CAA — June 15, 2020

Cynthia Navaretta.

We were saddened to learn of the passing of critic, publisher, and longtime CAA member Cynthia Navaretta last month at the age of 97. An active member of the organization and a founding member of the Women’s Caucus for Art (WCA), Navaretta was founder of the feminist arts publisher Midmarch Arts Press and a tireless advocate for women artists.

A memorial in her honor will be hosted via on Sunday, September 13th, 2020, at 6pm (EST). Members interested in attending are invited to contact cyncelebration@gmail.com to receive information and a link closer to the event. Readers are also invited to post comments and pictures about her life on a newly created Facebook page, here.

Cynthia Navaretta, art critic, curator, publisher, art collector, architectural engineer died on May 18, 2020 at 97

In her mid-twenties Cynthia Navaretta was immersed in the New York art scene from the early days of the ‘New York School’ and the influential “8th Street Club” (one of only 6 female members!) before she married Emanuel Navaretta, artist, poet, critic, professor and roommate of Franz Kline in 1950. Cynthia’s friends and neighbors in New York and Long Island (Springs in the Hamptons) included Jackson Pollack, Harold Rosenberg, Lee Krasner, Milton Resnick, Milton Avery, Franz Kline, the De Kooning’s (Elaine and Willem) Ibram Lassaw, David Smith, Phillip Pavia, Judy Chicago, Agnes Martin, Pat Passlof, Hans Hofmann, June Wayne, Susan Schwalb and a long list of other art legends.

In 1974, she was a founding steering committee member of ‘Artists Talk On Art’, the art world’s longest running panel discussion series. With her knowledge of the New York art scene, along with her professional qualifications in engineering and building, Cynthia served as a mayoral appointee to the Artists Certification Committee of the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs and later served as the public voting member of the powerful Loft Board in Manhattan for 20 years, deciding who was a bona fide artist and deserving of live-work studio space in converted factories. She was a founding member of the Women’s Caucus for Art, the Coalition of Women’s Arts Organizations, and also Women in the Arts.

She represented the United States at the 1985 UN Conference on Women in Kenya and served in similar capacities on other boards and meetings around the world including the International Festival of Women Artists, Copenhagen in 1980. She befriended many well-known African-American women artists throughout the United States. In 1995, she published the first definitive compendium of American women artists of color – Gumbo Ya Ya: Anthology of Contemporary African – American Women Artists with an introduction by Leslie King Hammond, Midmarch Arts Press.

As the founder of Midmarch Arts Press, she published numerous memoirs, guides, histories and anthologies by and about American artists, male and female including: Guide to Women’s Arts Organizations, Women Artists of the World edited by Sylvia Moore, Cindy Lyle and Cynthia Navaretta, Mutiny in the Mainstream — Talk That Changed Art (with Judy Seigal), The Heart of the Question, The Writings and Paintings of Howardena Pindell, introduction by Lowery S. Sims, Voices of Women, by Lucy Lippard, Postmodern Heretics, by Eleanor Heartney, Out of the Picture: Milton Resnick and the New York School edited and with an Introduction by Goeffey Dorfman and The First Wife’s Tale: A Memoir by Louise Strauss – Ernst, to name only a few.

Cynthia Navaretta at the National Women’s Conference in Houston 1977. Credit: Judy Seigel, via The New York Times

Her sharp mind, mixed with her organizational skills and ability to span many spheres of knowledge and personalities made her the ideal art panel planner, moderator or guest speaker. She was a beloved panel participant at College Art Association and mentored many young female artists. She was an active member of the International Art Critics Association and often traveled on their numerous trips around the world. She was also the publisher, along with photographer Judy Siegel, of the well-known Women Artist News (1978 – 1991), the first publication sent out on a regular basis covering the doings and activities of women artists; thus, publishing the first constant and continuing dialogue for women artists in the United States. A prodigious publisher, author and critic of feminist art in the United States Cynthia was one of the few who acknowledged and attracted regional and southern feminist artists whose work would otherwise most probably never have seen the light of day. Through the vehicles of Women Artist News and Midmarch Press, Cynthia was determined to document and champion many obscure female artists, offering them an exclusive avenue to introduce themselves and their work to a wider audience in the art world.

In her later years, she organized and curated her archives which were accepted by the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art. This written legacy from one of the leading feminist voices on art- is sure to be preserved, shared, and seen as a unique transcript of the American art experience.

In her ‘other’ life, Cynthia earned a master’s degree in mechanical engineering the 1940s. Returning to NYC, she was hired by the construction company Alvord & Swift. Established in 1911, Alvord became a significant contractor in the emerging specialty of HVAC design and construction. She designed and built many of the HVAC systems with Alvord & Swift for well-known skyscrapers in New York, including the famous Solow building. She also designed many of the HVAC systems at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. During her several year’s tenure there, she had the thankless job of training and preparing no fewer than three less talented male colleagues to assume the position and prestige of Vice President. This glass ceiling was the deciding factor in her eventual resignation. At that time, she was one of approximately 400 female mechanical engineers in the United States.

Throughout her engineering career, she held a variety of ambitious, supervisory positions. These included a managerial position for the ABC Television Network when the new Lincoln Center broadcast facility was being built. She also did a stint as an AMTRAK vice president, responsible for ‘new construction’ and ‘rights of way.’ She eventually retired to devote all her time to her publishing house and friends and family. But well into her nineties she could still be seen at art openings dressed to the ninths with her walker having arrived fashionably late by bus.

Remembrance by Susan Schwalb.

An Interview with Nicole Archer, Editor-in-Chief of Art Journal Open

posted by CAA — June 15, 2020

Nicole Archer.

We’re delighted to introduce readers to Nicole Archer, the current Editor-in-Chief of Art Journal Open (AJO), CAA’s online forum for the visual arts that presents artists’ projects, conversations and interviews, scholarly essays, and other forms of content from across the cultural field. Founded in 2012 as an open-access affiliate of Art Journal, Art Journal Open has been independently edited since 2014. It remains open access and is always free to explore.

Nicole Archer researches contemporary art and design, with an emphasis in textile and garment histories. She is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art and Design at Montclair State University, where she extends this research through a teaching practice that encourages students to explore politics and aesthetics via close examinations of style, embodiment, and desire.

Amidst the end of the academic year, we corresponded with her over email to learn more about her research, her thoughts on the impact of COVID-19, and her aspirations for Art Journal Open.

Where are you from originally?

I was born in Brooklyn and raised mainly in South Florida, but I spent most of my adult life in San Francisco. In 2018, I returned to New York City.

What pathways led you to the work you do now?

My path has been shaped by a long line of committed feminist art historians, theorists, and activists who have inspired me to pursue work that is wildly curious, ethically responsible, and politically committed to issues of social justice. This, coupled with the fact that I started my college career in the mid-1990s, when the field of Visual Studies was demanding that Art History be held accountable for the role it played in supporting certain cultural hegemonies. It was a time when we were recognizing the benefit that many art historical methods could bring to critical cultural studies (and vice versa).

When did you first become a CAA member?

I have been a CAA member since 2011, but I was an avid reader of Art Journal and The Art Bulletin long before that (thanks to my library access).

What are you working on or thinking about currently?

I am currently finishing a book manuscript that considers how textiles (our key mediums of comfort and security) have been strategically manipulated over the last two decades to aid in the systematic reshaping of what constitutes “legitimate” versus “illegitimate” forms of state violence. The book tells interwoven, materially grounded stories regarding global arts and design practice, on the one hand, and military, police, and governmental action, on the other, to theorize how feelings of insecurity are produced, aesthetically.

What are your thoughts on the impact of COVID-19 on the work you do? On the field?

I think the current pandemic makes two things particularly clear. First, it highlights the important role that art and design can play in helping a society understand (and bear) emergent and acutely difficult circumstances. From movie marathons, artist talks, and book readings that we have enjoyed during our nights spent ‘sheltering in place,’ to the protest banners, photographs, and balcony performances that have led our communities towards acts of collective care and solidarity with one another.

Second, COVID-19 puts the varied inequities that underwrite the field in high relief. It makes the economic precarity of so many cultural workers glaringly obvious, and it forces us to recognize how undervalued cultural work actually is. We need to ask why we have allowed the arts to become so defunded and privatized (despite the social value it clearly delivers). Calls for austerity are circulating, and we know this means further cuts to already underfunded public arts initiatives. We need to resist this and seize this moment as an opportunity to insist on our value. We need to stop undercutting ourselves and our peers, and refuse to accept the exploitation of adjunct professors and graduate student teachers. We must do this as we push against the increasingly prohibitive costs of arts education.

What led you to be interested in working on Art Journal Open?

What led you to be interested in working on Art Journal Open?

It is our shared responsibility, as arts and design professionals, to constantly “check” our field of practice—to find time to celebrate what we are doing well, and to redress and learn from our shortcomings. I believe this responsibility is a cornerstone of AJO’s editorial mission. Working on AJO is a unique opportunity to hold myself, and others, accountable on this front.

What is your vision for Art Journal Open during your tenure?

I hope to build on the solid foundation laid by the journal’s previous editors, and to further emphasize the open dimension of the publication’s identity—to treat “Open” as a verb, a call to action. We hope to accomplish this by leveraging the journal’s digital format, to open space for more multi-media Creative Projects, and to take advantage of our lack-of-paywall to help draw new readers to AJO and new voices to CAA.

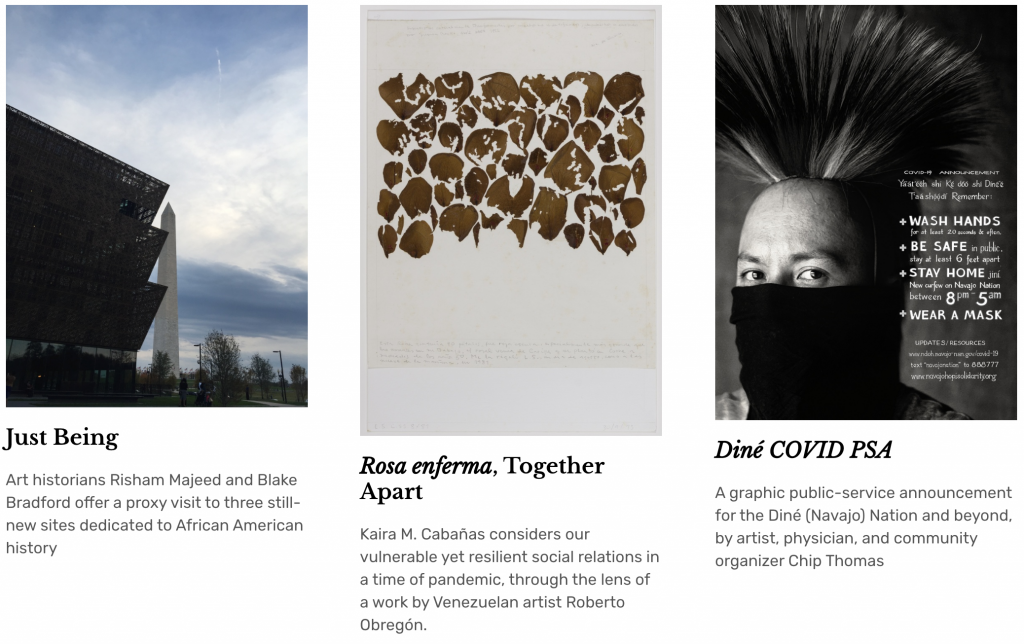

The first three pieces published after Nicole Archer fully took over as Editor-in-Chief of Art Journal Open.

What would you say is your top arts-related recommendation (book, website, resource) at the moment?

I know I am late to this, but I recently found an online radio station called NTS and it is giving me life! I miss trusting my night to a DJ, hearing a new song out of nowhere, and dancing with strangers. I am also tired of soundscapes controlled by algorithms. People should give it a listen in their studios and kitchens, and at their computers and writing desks.

View this post on Instagram

A favorite artwork?

Last year, I had the opportunity to see Sonya Clark’s Monumental Cloth, The Flag We Should Know at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, and I have not been able to stop thinking about it since. Clark’s work epitomizes the important role art can play in ensuring that political discourse maintains its complexity in the face of a mediascape set on transforming these conversations into flat lines in the sand.

At the center of the exhibit was a monumental replica (15’x30’) of a white dish towel waived by Confederate troops in April 1865, before General E. Lee negotiated the terms of the Confederacy’s surrender. Displayed in a manner akin to the Star Spangled Banner (a centerpiece of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History’s collection), Monumental Cloth presented the Confederate Truce Flag as testament to a decisive moment in US history. It demanded that we ask why we do not know this flag, as a means to discuss anti-Blackness and the persistence of white supremacy in the United States. It provided a poignant, aesthetic counterstrategy to other manners of “memorializing” the Confederacy. The exhibit offered spaces of contemplation alongside opportunities for direct action—by setting-up looms that visitors could use to weave additional Truce Flag replicas, in opposition to the endless flow of commercially produced items made to bear the image of the Confederate Battle Flag.

What are you looking forward to?

Honestly, I am looking forward to the end of the Trump presidency, and to the possibility that the moment we are in could force real political and cultural change; that conversations around universal basic income and healthcare will gain traction, and that widespread recognition of the systemic racism inherent in the criminal justice system will open the door to both abolishing the prison system and defunding and demilitarizing the police that tyrannize communities of color in the US.

NICOLE ARCHER BIOGRAPHY

Nicole Archer researches contemporary art and design, with an emphasis in textile and garment histories. She is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art and Design at Montclair State University, where she extends this research through a teaching practice that encourages students to explore politics and aesthetics via close examinations of style, embodiment, and desire.

Her work has been published in various journals, edited collections, and arts publications, including: Criticism: A Quarterly Journal for Literature and the Arts; Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture; Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility (published by the New Museum + MIT Press); Where are the Tiny Revolts? (published by the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts + Sternberg Press); Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory.

CAA Solidarity Statement

posted by CAA — June 05, 2020

The College Art Association (CAA) condemns all forms of systemic racism, violence, bias, aggression and the marginalization of Black, Indigenous, and all Peoples of Color (BIPOC) as well as discrimination based on race, intersectionality, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. As a community of those who study, teach, write about, advocate for and/or create art and design, we have committed our life’s work to learning-from, exploring-with, and creating-towards our shared humanity. As a membership organization we choose to use our voices to speak to one another and speak up for one another.

To ensure lasting change:

- We encourage the creative community to examine biases, micro-aggressions, and who we leave out.

- We encourage learning from sharing narratives of BIPOC.

- We encourage providing services and support for underrepresented and entirely non-represented members of the community.

- We will work to create and promote standards and systems that actively support equity in anti-racist teaching, research, publication and creative practices.

In solidarity, CAA, its board, and its staff continue to amplify equity, diversity, and inclusion and call our community to action with us in this commitment to change.

CAA Values Statement on Diversity and Inclusion

For additional resources see the Committee on Diversity Practices as well as resources shared via CAA News, Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

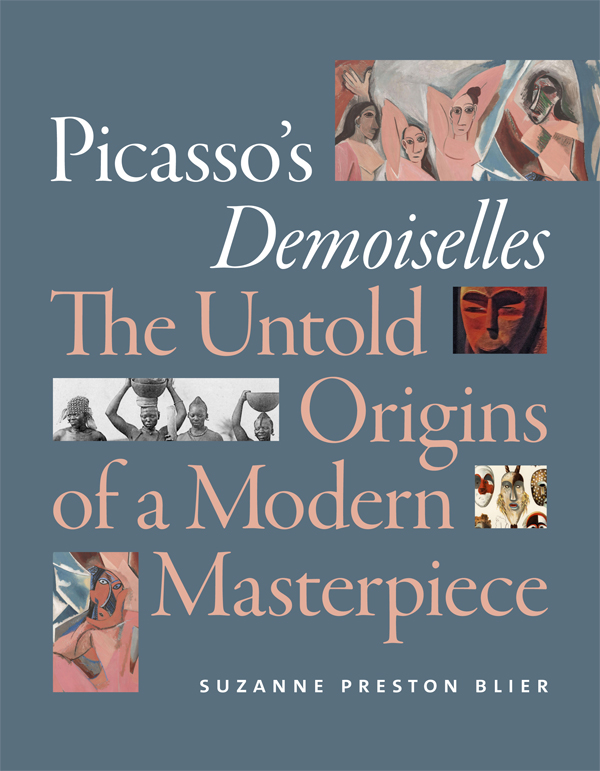

An Interview with Suzanne Preston Blier on CAA’s Code of Best Practices and Publishing with Fair Use

posted by CAA — May 19, 2020

In 2019, Suzanne Preston Blier, professor of African art at Harvard University and former president of CAA, published a major book on Picasso’s use of global imagery, Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece. In addition to its scholarship the book is groundbreaking for its reliance on fair use, the principle within US copyright law that permits free reproduction of copyrighted images under certain conditions. CAA led the way among visual arts groups in calling for reliance on fair use, producing in 2015 its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

In 2019, Suzanne Preston Blier, professor of African art at Harvard University and former president of CAA, published a major book on Picasso’s use of global imagery, Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece. In addition to its scholarship the book is groundbreaking for its reliance on fair use, the principle within US copyright law that permits free reproduction of copyrighted images under certain conditions. CAA led the way among visual arts groups in calling for reliance on fair use, producing in 2015 its Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

In this interview with Patricia Aufderheide, university professor and founding director of the Center for Media & Social Impact (CMSI) at American University, and a principal investigator in the CAA fair use project, Blier relates how she became an inadvertent pioneer of fair use in art history.

An Interview with Suzanne Preston Blier, Harvard University

By Patricia Aufderheide, American University

I met Prof. Blier, an award-winning art historian, when CMSI joined others in facilitating the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts for the College Art Association (CAA), with funding from the Samuel H. Kress and Andrew W. Mellon Foundations. Fair use is the well-established US right to use copyrighted material for free, if you are using that material for a different purpose (such as academic analysis, for instance) and in amounts relevant to the new purpose. Blier was the incoming president, as the Code launched.

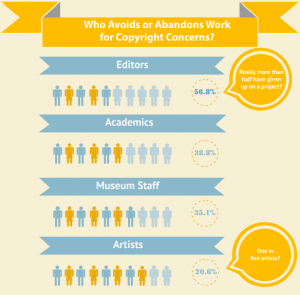

The project addressed a huge need. Art historians, visual artists, art journal and book editors, and museum staff all have faced major hurdles in accomplishing their work because of copyright. Art historians avoided contemporary art in favor of analyzing public domain material. Visual artists hesitated to undertake innovative projects that reuse existing cultural material. Editors, or sometimes their authors, faced monumental bills for permissions and sometimes those permissions depended on an artist or artist’s estate agreeing with what they say. Museums hesitated to do virtual tours, or use images in their informational brochures, or even to mount group exhibits, because of prohibitive permissions costs. All together, some people in the visual arts called this “permissions culture.”

Once the Code came out, some things changed immediately. Museums rewrote their copyright use policies. Artists made new work. CAA’s publications—some of the leading journals in the field—adopted fair use as a default choice.Yale University Press prepared new author guidelines for fair use of images in scholarly art monographs to encourage fair use. Blier was one of the Code’s champions.

And then she needed it herself. As she began work on her most recent book, which ultimately resulted in Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece (Duke University Press, 2019, winner of the 2020 Robert Motherwell Book prize for an outstanding publication in the history and criticism of modernism in the arts by the Dedalus Foundation), she realized the subject faced the stiffest possible copyright challenge. To tell her story, she would have to be able to show images from a variety of artists, most challengingly, Picasso. She thought of Duke University Press, a publisher that has been willing to go ahead of others on fair use. So Blier approached them. Duke was very supportive, and they ended up hiring extra legal counsel for this. In the end, Blier said, she had to rewrite certain sections, and redo some images at the suggestion of outside counsel, to strengthen the fair use argument.

Blier tells the story of how the book got out into the world (and won an award), below.

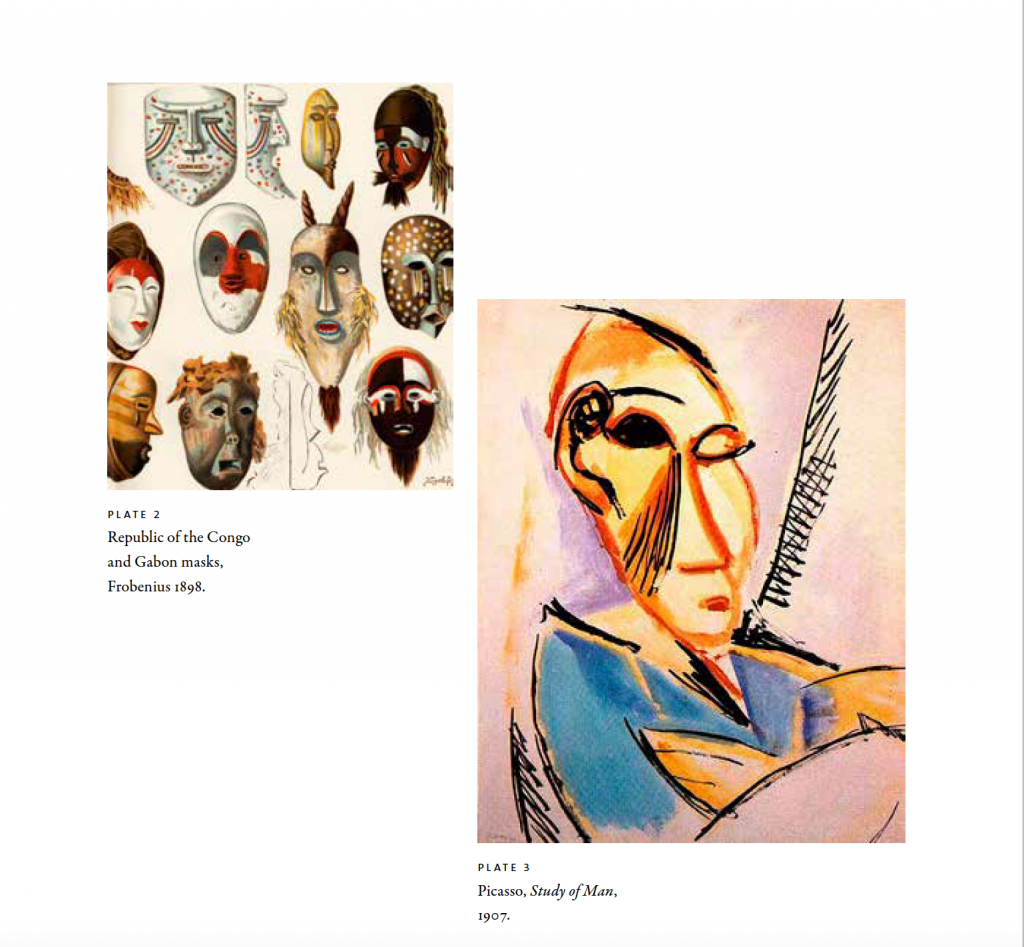

Figure 1. Congo masks published in Leo Frobenius’ 1898 Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas alongside Pablo Picasso’s Study of Man (1907). The Congo mask at the bottom, second from the left is the likely source for the crouching demoiselle. The mask at the top left shows tear lines from the eyes crossing diagonally down the cheeks similar to Picasso’s preliminary study for one of the men in an early compositional drawings for the canvas.

You’re an expert in African art. How did you end up writing a book about one of the most famous modernist artists?

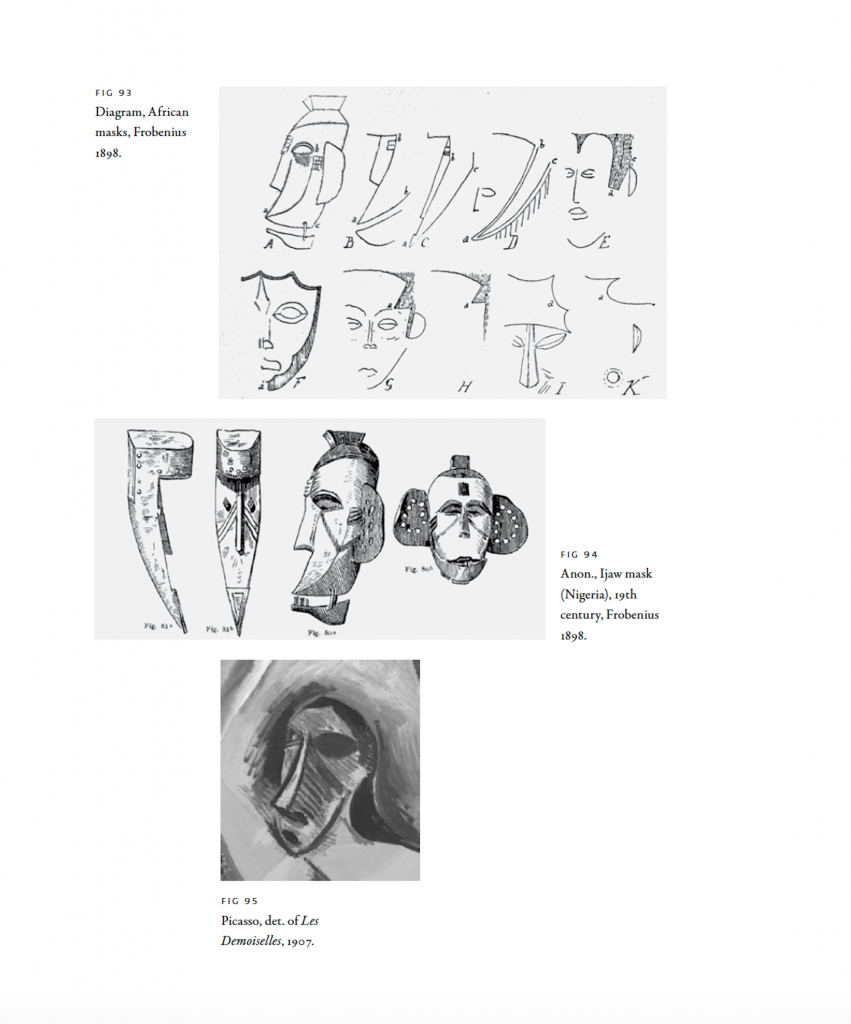

This is a book I never intended to write; it found me. For my previous book, Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba: Ife History, Power, and Identity, I was doing those last-minute bits of work in the library to check sources, and I pulled out a book adjacent to the book I was looking for, an old book by the German anthropologist, Leo Frobenius. I hadn’t read it since graduate school. As I opened it up, I looked down and I said, Wow, this is a book on African masks and they look like they’d be the ones Picasso used as models for his famous 1907 painting Demoiselles d’Avignon. At the time I had first read the book, Picasso’s drawings for the painting hadn’t been released. This time I saw it differently and as I was looking at it in the library, I saw there was tracing paper over the pictures. There was a line drawing covering each mask, and that seemed significant too.

The next thing I knew, I was hunting for a book from the Harvard library on Dahomey women warriors. It turned out it was in the medical school library, which should have been a sign. When I picked it up at the main library and flipped it open, I thought, Oh my god, it’s pornography! It was photos and line drawings of women around the world, in supposed “evolutionary” order. Photos of naked women begin with so-called “archaic,” in Papua New Guinea, right through to southern Europe, then Denmark. In the library I’m bending over, kind of hiding it, out of embarrassment. I bring it home and realize, Ohhhh! Here’s another key source for Demoiselles. This volume, which was by Karl Heinrich Stratz, had gone through multiple editions, and one was published about the same time Picasso stopped using living models. Then I found another book, by Richard Burton, which had a rendering that Picasso clearly used for his 1905 sketch Salomé.

What happened next was the clincher. I went to Paris to lecture at Collège de France. The week before my lectures, I went to hear another speaker at the Collège, a medieval historian. One of the first slides he presented was a work from a medieval illustrator, Villard De Honnecourt. This book was a modern edition of an illustrated medieval manuscript, published in the right time frame for Picasso to have seen it. And I thought, Well, here’s another source Picasso used.

Later I was also able to rediscover a photo that allowed me to date the painting to a single night in March 1907. The scene is often identified as a brothel, but bordel in French doesn’t mean bordello, but rather a chaotic or complex situation. It was my belief that Picasso was creating a time-machine kind of image of the mothers of five races, as he understood them from the Stratz ethno-pornography book and other sources, each depicted in the art style of that region or period. My larger argument is not only that Picasso was using book illustration sources, but also that these books invite us to see the canvas in a new light, and that, for Picasso, the painting has its intellectual grounding in colonial-era ideas about human and artistic evolution.

Figure 2. Illustrations from Leo Frobenius’ 1898 Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas showing (top two rows) the visual development of a mask into a human face. The middle illustration ,from the same Frobenius book shows line drawings of ijaw masks from Nigeria. The bottom image is a detail of the standing African figure from Picasso’s 1907, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon which appears to be based on a combination of these two masks.

What a sleuthing job! And so you decided to write the book then?

I wrote the first two chapters while I was in Paris doing the lecture. I saw it not as a coffee-table art book, but the kind of book you put in your knapsack as you head off to a long ride on the subway.

It was easy to write, but it was a very different story for the images. I immediately got a trade publisher in Britain to agree to publish it, and then they said they could not do it, because of problems getting permission to reproduce images from the Picasso Foundation.

The Picasso Foundation is notorious for making it difficult to access Picasso images, isn’t it?

The price of permissions is high, and this Foundation like many estates is interested in guarding the artist’s reputation as well. The difficulties of publishing on Picasso have been manifested in how little publishing was being done, and how scarce the images were in that work. Since 1973, there have been few heavily illustrated books about Picasso, except by wealthy individuals or museums in relation to an exhibition. I had heard about Rosalind Krauss publishing a work without permissions—at least that’s what I heard—anyway, she used very few images. Leo Steinberg apparently had not been able to arrange the rights for a work he wanted to do, a book edition of his two seminal articles on Les Demoiselles.

Although I hadn’t realized it until recently, in September 2019 there was an important case in the US, about a set of illustrated books by Christian Zervos with a wide array of Picasso illustrations. The case was started in France, but a US judge has allowed fair use.

But generally, yes, there’s common wisdom among art historians that the Picasso Foundation is a formidable challenge.

So how did you proceed when the first publisher backed out?

I was disheartened, but I got an agent. He sent it off to ten or twelve trade publishers worldwide—and came up with nothing.

Then I realized I was going to have to go to a university press. That was a big decision. The trade publication will pay for the images, and do all the work on the rights clearance. But with a university press, you’re on your own.

One of the first people I contacted was legendary editor Ken Wissoker at Duke University Press. He was interested, but then came the issue of the images. I may have broached fair use with him from the start. The manuscript had gone through peer review and it was in great shape except for this copyright issue. I had quite a number of images—in the end, it was 338. At Duke, they won’t begin the editorial process until you have all the copyright clearances on images done. So I began the difficult process of deciding how to get the images.

Were you in contact with the Picasso Foundation directly?

I did contact them, in order to let them know about the project in general. I was doing final research work in Paris. I had framed the book as a travelogue in part addressing my discovery of these sources. I also wanted to find out so much more about Picasso. I’m not a modernist, I’m an outsider to the field. So I worked hard to get as much insight and criticism of the manuscript from specialists as I could.

I made it a point to meet with people at the Picasso Foundation. I had a Powerpoint of the images, which I showed to one of the key people there. Later I wrote to them, “here’s the manuscript, let me know if you have any thoughts.” And I heard nothing back. I had heard that with some manuscripts, they have been concerned one way or another. I didn’t want their permission for the intellectual content, but since they knew this artist and his life and family better than any academic could, I wanted their insights.

And then you started to look for permissions?

Well, I began to think about the cost of acquiring the images. The process is such that you have to go through the Artists Rights Society (ARS, a US licensing broker). And to get a price, you have to furnish the number of images, how many are color, the size of the print run, the prospective profit, and a whole series of things we could not know. Duke wouldn’t even look at the project editorially without having the rights in hand. I had heard difficult stories—that they were interested in looking at the galleys along the way, and requesting changes, for quality control, but it wasn’t possible to do this and work with the press.

If I had to guess, I would say that it might have cost me something like $80,000 of my own money to purchase the minimum number of images for this scholarly book, from which I expect to make no money, or very little.

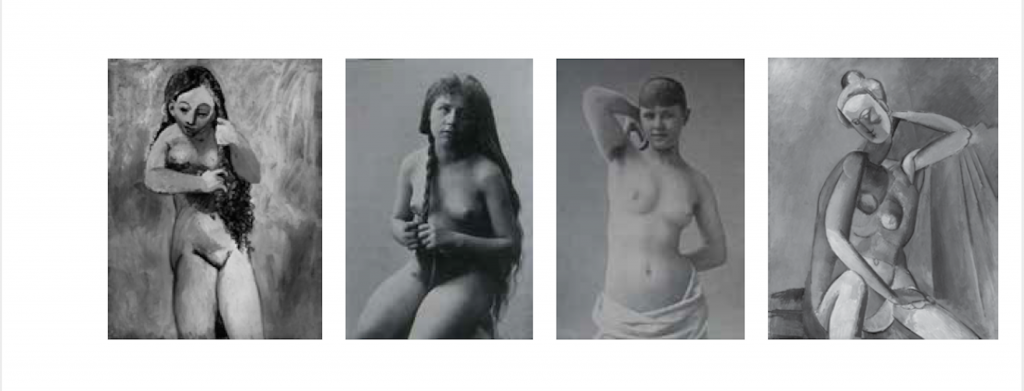

Figure 3 from left to right: Pablo Picasso, Nude Combing Her Hair, 1906; Girl braiding hair from C. H. Stratz, La beauté de la femme, 1900 (Paris); Girl from Vienna from C.H. Stratz, La beauté de la femme, 1900; Picasso Seated Female Nude, 1908. Over the course of his long career Picasso would continue to use key visual insights from Frobenius, Stratz, and other illustrated sources he was exploring in this late 1906 to early 1907 period.

So how did you come to the decision to use them under fair use?

I had been president of CAA in 2016-17, and a longtime promoter of fair use and IP issues more generally. I was involved in the creation of the Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts. For me, CAA’s role in fair use is one of the most important and radical (in a positive way) things that it has ever done.

I decided that fair use would make the most sense in this context. This was a book about an important modern artist. In addition, I’m a senior scholar—this was not my first publication. If the worst happened, if I had problems, well, I’ve had a great career and this would not harm it. I have tenure and so on. Also, as the then-president of CAA, I thought it was important to do this.

Besides, this to me was part of a larger picture of what I had done in my larger career. I’m very active locally in civic affairs, and really interested in promoting transparency, and democratic ideals. I was also very fortunate to have Peter Jaszi, a foremost legal scholar on fair use (and another principal investigator on the CAA project), working with me. At his suggestion, I took out an insurance policy, which for a fee—I think about $5,000—(with a $10,000 deductible) I was able to lower my anxiety level. I also paid $400 for an attorney to look over the insurance contract. And I had good friends like you, who when I got cold feet assured me it was the right thing to do. And of course, Duke is a publisher that has been willing to go ahead of others on fair use.

Can you give me an example of something you had to change in the text to strengthen the fair use argument?

With a museum photograph of an African mask, for example, I had to explain why this particular way of photographing the work was critical to the argument in my book. I had to ad a few sentences to justify my selection of several Picasso works as well. I also had to give reasons in my text for why each of the chapter epigraphs was necessary.

Did you have to alter the use of imagery in any way to accommodate fair use?

There are changes the press made, design-wise, that reflected in part the decision to employ fair use. Many of the photos are shown in black-and-white and the majority are reduced in size. I was constrained by the fact that I could only employ fair use if I could get access to the materials without going through the Picasso Foundation. So I had to acquire nearly all the images from published books, and many of the Picasso images were published in black and white and at a very small size, in a grainy context. I had to spend a lot of time hunting down the best possible images to use. In my book they are shown in relatively small size, along with information on where you can find color versions online.

That didn’t bother me too much, though. For readers and viewers at this juncture in the Internet era, we have become expert at extrapolating the fuller figure from a small image.

There is also a small spread of color images, a couple Picasso works as well as from other artists. For these images color was central to the book.

The decision to publish largely in black-and-white was, I think, also related to the fact that the Picasso Foundation and others are concerned that color representations be incredibly accurate, and it is very hard to get the color exactly right, when copying from books. You also have an issue with paper quality in getting accurate representation.

The cover is a handsome design, and very clever. They broke up the images into thumbnail-like sections, requiring you as a viewer to put them together as one image, similar to how Picasso was thinking in the early stages of cubism, where you as a viewer of an assemblage have to assemble them in your own mind, to make it work for you as a whole.

How was the book received?

It was a finalist for the Prose Prize, a prize of publishers to authors. My previous book won it in 2016. I didn’t expect to win it this time again, in 2019. I was very honored that it was a finalist. It was also featured in the Wall Street Journal’s holiday art book list. And then, just recently, it won the Robert Motherwell Book Award.

Has the Picasso Foundation seen the book?

To date I’ve heard nothing. I was thinking earlier that the Picasso Foundation might want to stop it pre-publication. So much so that when I came back from travel in Africa, I went first to my academic mailbox, and was relieved when I saw no big legal envelope. But there has been no pushback. I certainly gave them the opportunity to comment on the content while it was still in manuscript. And last April or May, I went to France to meet with the curators at Musée Picasso about contributing an essay to a catalog. I sent them an article draft which they decided not to publish, which is fine, but also sent them a copy of the manuscript, and of course the Musée speaks to the Foundation.

Interestingly, the two cases where the Foundation has sued or prevented publication that I know of have to do with children’s books about Picasso. I don’t know what that means.

Does the wider art history community know about this?

I hope this personal story makes a difference. We still have a lot of educating to do, in spite of the work we did around the Code. I continually get, on the art history listservs, questions—How can I get permission, and I always say, Use fair use. People still don’t trust it or believe it’s more difficult than it is.

At the CAA conference I just went to in Chicago, there seems to be a division between presses. Presses at private universities–Yale, Princeton, MIT, Duke—seem to feel more comfortable exploring this. But for university presses at some public institutions, these legal issues have to be taken up with the state attorney general, and there can be real nervousness stepping outside a narrow parameter. I learned this speaking to an editor at a state university press in a progressive state, who believes they’re being held back because of this fear.

I was pleased to see at this same conference a pamphlet on fair use by Duke University Press’s former Director, Steve Cohn. In his essay, he mentions my Picasso book and how happy he is that Duke chose to publish it this way. I figured, if Steve is openly talking about this fair use project, then the proverbial cat is out of the bag, and I could be more open and provide some of the back story from my end.

CAA’s scholarly publications, The Art Bulletin, Art Journal, and Art Journal Open rely on fair use as a matter of policy, and indicate when they do so in their photo credits. View a complete discussion of fair use and CAA’s Code of Best Practices.

Announcing the 2020 Recipients of the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions

posted by CAA — May 12, 2020

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In fall 2018, we announced CAA had received an anonymous gift of $1 million to fund travel for art history faculty and their students to special exhibitions related to their classwork. The generous gift established the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions.

The jury for the Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions has now selected the second group of recipients as part of the gift. This year’s awardees are:

Holly Flora, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

Course: Art, Cosmopolitanism, and Intellectual Culture in the Middle Ages

Exhibition: Medieval Bologna: Art for a University City at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville, TN

Caroline Fowler, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA

Course: Slavery and the Dutch Golden Age

Exhibition: Slavery at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Maile Hutterer, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR

Course: Time in Medieval Art and Architecture

Exhibition: Transcending Time: The Medieval Book of Hours at The Getty Center, Los Angeles, CA

Erin McCutcheon, Lycoming College, Williamsport, PA

Course: Art & Politics in Latin America

Exhibition: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Unstable Presence at SFMOMA, San Francisco, CA

Shalon Parker, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA

Course: Women Artists

Exhibition: New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, CA

Rebecca Pelchar, SUNY Adirondack, Queensbury, NY

Course: Introduction to Museum Studies

Exhibition: Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection at the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC

As museums and schools have moved online in light of the coronavirus pandemic, we are being as flexible as necessary with the dates of travel to accommodate all award winners and classes.

The Art History Fund for Travel to Special Exhibitions supports travel, lodging, and research efforts by art history students and faculty in conjunction with special museum exhibitions in the United States and throughout the world. Awards are made exclusively to support travel to exhibitions that directly correspond to the class content, and exhibitions on all artists, periods, and areas of art history are eligible.

Applications for the third round of grants will be accepted by CAA beginning in fall 2020. Deadlines and details can be found on the Travel Grants page.