CAA News Today

International Review: A Centenary Celebration of Chilean Artist Nemesio Antúnez

posted by CAA — November 14, 2019

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Sophie Halart, Professor of Art History at the Universidad Adolfo Ibañez, Santiago, Chile.

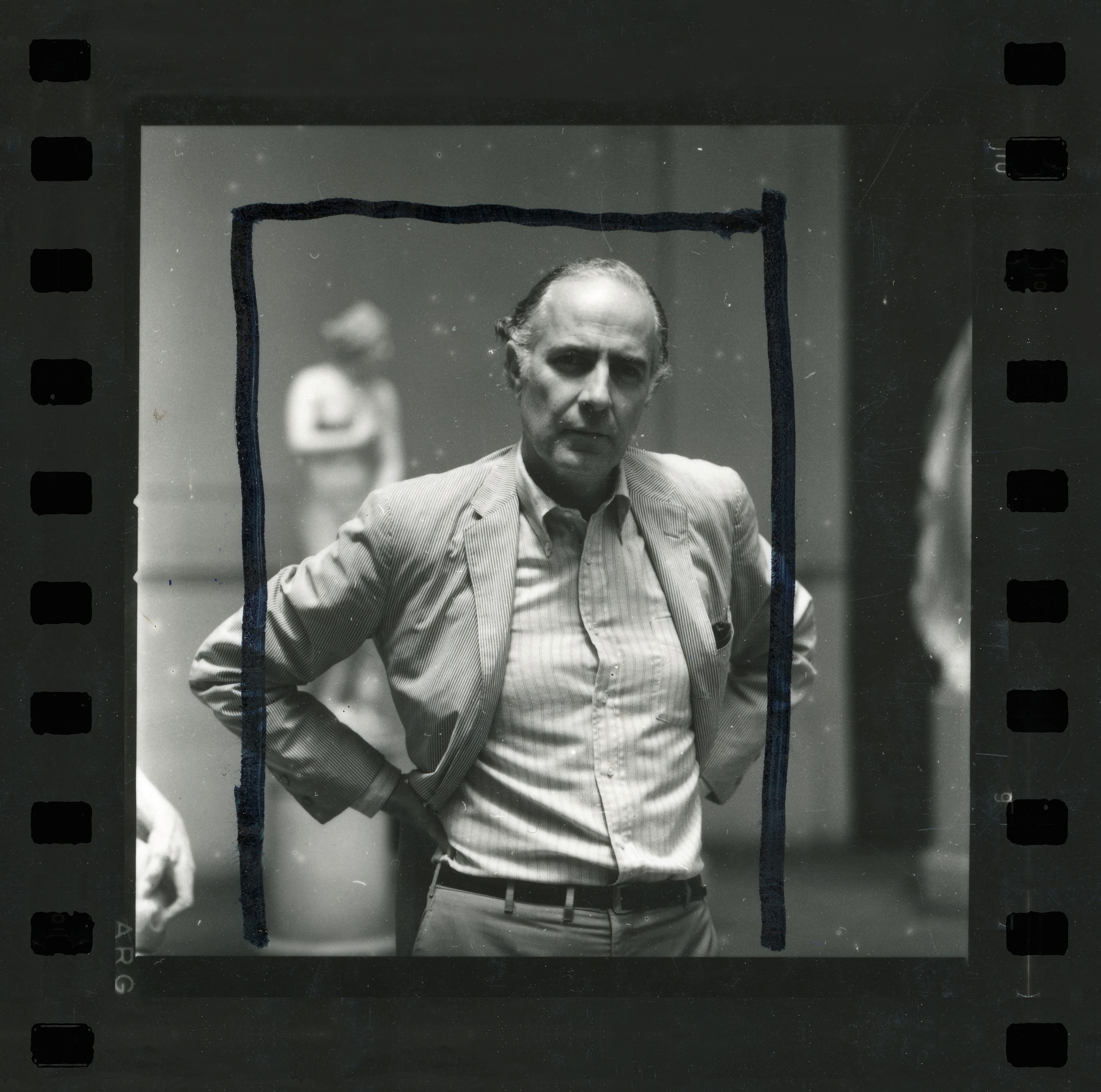

Figure 1. Promotional image of the Antúnez centenary celebration (photograph provided by the Ministerio de las culturas, las artes y el patrimonio)

In 2018-19, Chile celebrated the centenary of the visual artist, educator, and cultural figure Nemesio Antúnez (1918-93) (Fig. 1). The initiative, led by the family foundation in charge of Antúnez’s legacy, comprised several events, including roundtable discussions and archival and retrospective exhibitions throughout the country. In Santiago, the Museo de Bellas Artes (Fine Arts Museum) and the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (Museum of Contemporary Art), two institutions whose very structure and mission were profoundly modified under Antúnez’s leadership, organized a series of three exhibitions, each focusing on one aspect of his prolific career.

Figure 2. Manifiesto, installation view (photograph provided by the author)

The Museo de Bellas Artes hosted Manifiesto (Manifesto), a comprehensive retrospective of Antúnez’s artistic production (Fig. 2). Showcasing a selection of paintings, engravings, notebooks, and photographic archives, curator Ramón Castillo retraced both Antúnez’s international formation and his influence on the Chilean art scene. Initially trained as an architect in Chile, Antúnez secured a Fulbright grant in 1943 to study art in New York, where he attended Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17. Upon his return to Santiago in 1956, he founded his own engraving workshop, Taller 99, attended by important national artists like Roser Bru and Juan Downey. Antúnez’s interest in art education also led him to take part in the creation of the Universidad Católica’s School of Arts in 1959. Castillo’s exhibition offers an intimate gaze into Antúnez’s life and work, revealing the complexity of both. More importantly, the show considers the artist’s standing at the threshold of two epochs. A product of cosmopolitan modernity, Antúnez felt more acutely than most the changes that entry into the contemporary age would bring to Latin American art.

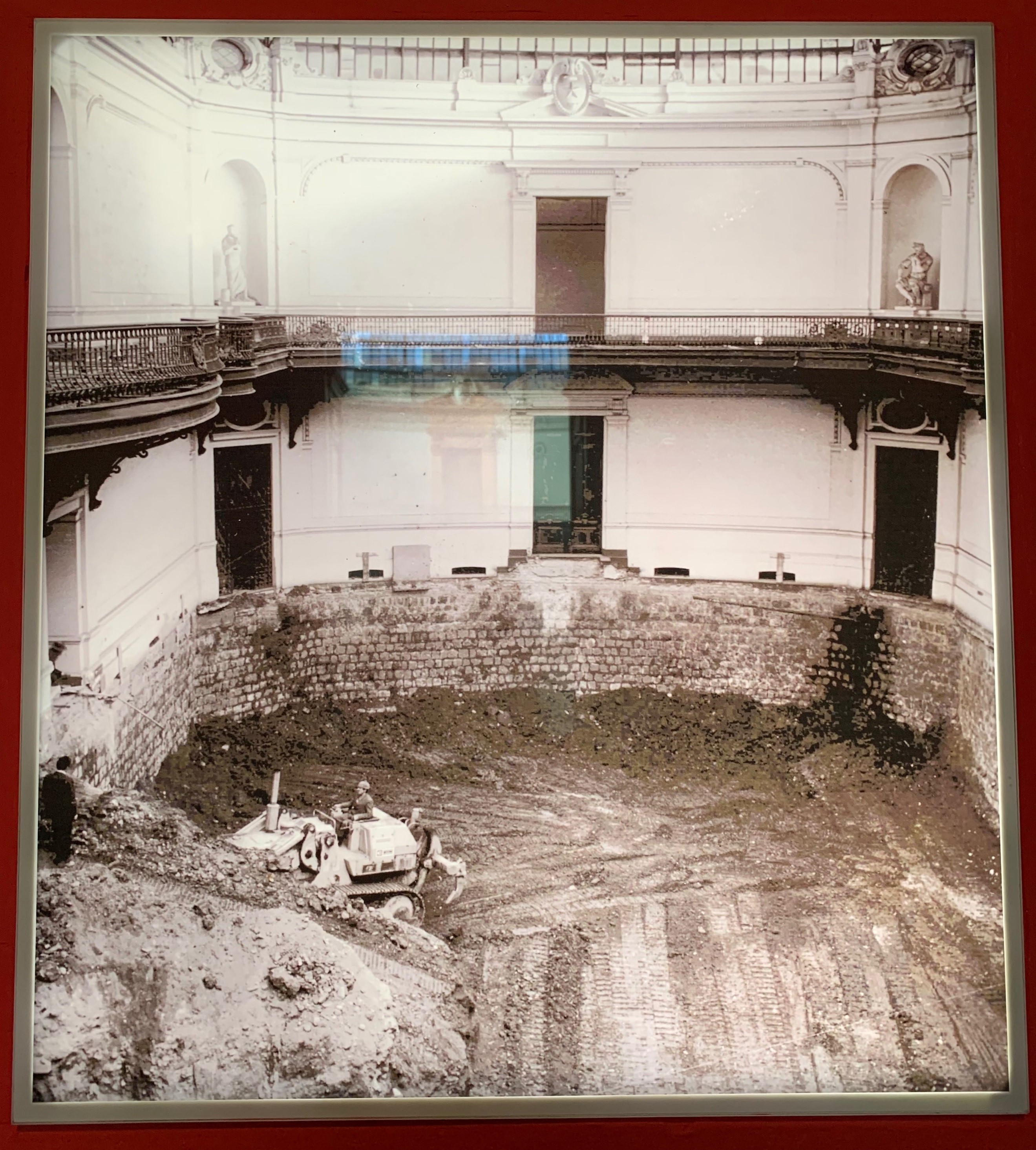

Figure 3. Construction of a lower ground floor at the Museo de Bellas Artes, Santiago (photograph provided by the author)

This temporal aspect of Antúnez is even more clearly evidenced in the second exhibition hosted by the museum. El Museo en Tiempos de Revolución (The museum in times of revolution), curated by Amalia Cross, examined the pivotal changes made by Antúnez when he became the Fine Arts Museum’s director in 1969. The appointment, which just preceded the presidential election of Socialist candidate Salvador Allende, reflected the implementation of an equally revolutionary agenda that sought to do away with the museum’s elitist image. Appealing to the etymological roots of the word museum, Antúnez opened the institution’s doors to a plurality of artistic media, including music and live performance, while striving to attract new, more diverse audiences. He also oversaw an important refurbishment of the building that included the construction of an additional, underground exhibition space dedicated to recent art (Fig. 3).

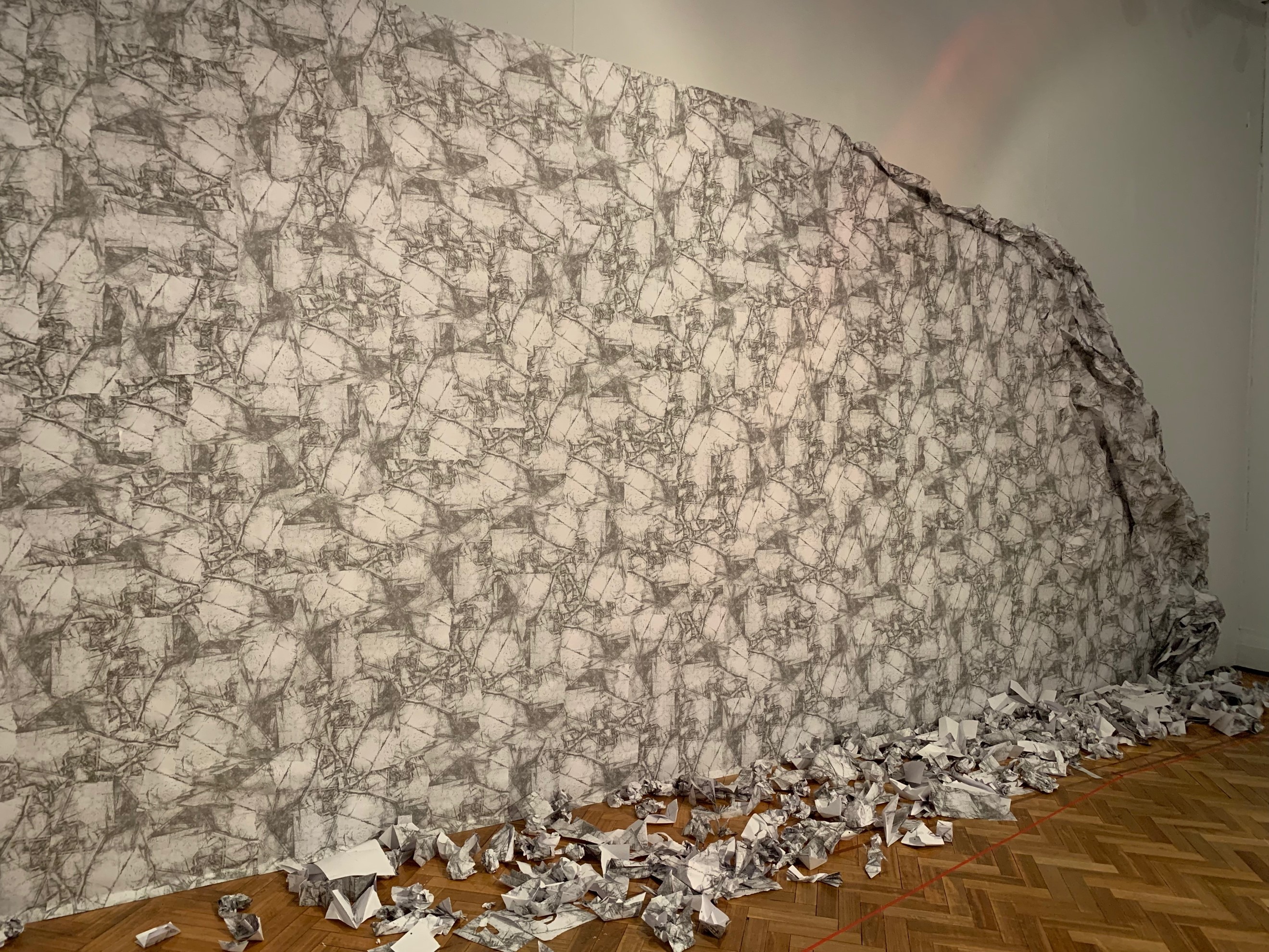

Figure 4. Liliana Porter, Wrinkle Environment, 1969. 2019 re-creation of the piece in the Museo de Bellas Artes, Santiago (photograph provided by the author)

While Antúnez shared some of the democratizing ideals of culture advocated by Allende’s government, his project to open the museum to new audiences and artistic practices—including an incipient conceptual scene—rejected strictly programmatic and propagandistic ends. Some memorable on-site interventions were performed under his tenure, including Juan Pablo Langlois’s Cuerpos Blandos (Soft bodies, 1969) and Cecilia Vicuña’s Otoño (Autumn, 1971), both pioneering the field of institutional critique in Chile. Through a display of archival documents and photographs, Cross’s curatorial work invites comparison of the infrastructural and conceptual modifications that took place in the museum. The exhibition also recreates an installation produced by Liliana Porter whom Antúnez had invited to exhibit in June 1969 along with Luis Camnitzer. A founding member of the New York Graphic Workshop (along with Camnitzer), Porter produced one of her “Wrinkled Environments,” a paper tapestry that covered the walls of the museum and which visitors were invited to modify by tearing away some of the sheets and discarding them on the floor (Fig. 4).

The 1973 military coup, which took place on the eve of an exhibition on Mexican muralism due to open a few days later, put an abrupt end to this period of political and artistic experiments and sent Antúnez into European self-exile. The return of a democratic government in 1990 allowed him to resume his work as director of the museum, a position he occupied until his death three years later.

Figure 5. Nemesio Antúnez: Panamericano, installation view (photograph provided by the author)

While these first two exhibitions focused on Antúnez during his time as director of the Bellas Artes, the show Nemesio Antúnez: Panamericano, which took place in the adjoining building of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (MAC), focused on a previous and lesser-known period of Antúnez’s professional life, namely his tenure as director of that museum (1962–64) and his influential role in rethinking contemporary artistic creation along transdisciplinary and cross-regional lines. (Fig. 5). According to the show’s curator Matías Allende, Antúnez remains a ghostly figure in the MAC, his vision haunting an institution which, when it opened in 1946, was the first museum of contemporary art in Latin America. Allende’s research focuses on the way Antúnez contributed to rethinking contemporary creation along three axes: the national, the popular, and the American. Indeed, while the off-site events he staged in modest neighborhoods of Santiago revealed an early ambition to democratize art, the organization of the first Biennial of American Printmaking (1963) showed Antúnez’s desire to build a bridge between avant-garde art and popular crafts on a continental scale. Moreover, using the connections he had made while studying in the US, his acquaintance with Alfred Barr in particular, Antúnez also piloted the organization of exhibitions comprised of works on loan from MoMA’s permanent collection. In this exhibition, Allende opted for a densely documented installation that could be overwhelming at times. Thankfully, this encyclopedic fervor was offset by the presence of short videos the curator commissioned from the video artist Flavia Contreras. Somewhat dramatizing Antúnez’s aura as an educator, these videos were fictional recreations of the cultural TV program Ojo con el arte (Watch out with the art) that Antúnez hosted for two seasons on national TV (in 1970–71 and for a second run between 1990 and 1993).

While the three exhibitions discussed above were products of independent research and curatorial planning, each of which focused on one facet of Antúnez, they may also be understood as part of a collective portrait enriching the prolific and multifarious contributions he made to Chilean art and cultural life. At the same time, the pivotal role played by the private Fundación Nemesio Antúnez in the planning of the centenary, an organization founded and directed by relatives of the artist, also begs the question of the public sector’s passivity in providing official recognition to one of Chile’s most important cultural figures. While the Fine Arts Museum, a state entity, and the MAC, a university institution that also relies on public support, did eventually take an active part in the celebration, the delays that occurred in the opening of the exhibitions were due in part to an initial lack of enthusiasm on the part of the State. Thus, while the exhibitions comprising the backbone of the centenary celebrations must be praised for their quality, they also highlight the problematic absence of public funding for culture in Chile and the ways in which the writing of art historical narratives continue to be relegated to the goodwill of private institutions and family estates.

Announcing the 2020 CAA-Getty International Program Participants

posted by CAA — October 07, 2019

CAA-Getty International Program Participating Alumni (left to right) Chen Liu, Nazar Kozak, Katarzyna Cytlak, Nadhra Khan, and Sarena Abdullah at the 2019 Annual Conference in New York. Photo: Ben Fractenberg

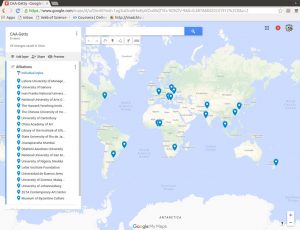

We’re pleased to announce this year’s participants in the CAA-Getty International Program. Now in its ninth year, this international program supported by the Getty Foundation will bring fifteen new participants and five alumni to the 2020 Annual Conference in Chicago, Illinois.

The participants—professors of art history, curators, and artists who teach art history—hail from countries throughout the world, expanding CAA’s growing international membership and contributing to an increasingly diverse community of scholars and ideas. This year we are adding participants from four countries not included previously—Bolivia, Saudi Arabia, Côte d’Ivoire, and Singapore—bringing the total number of countries represented by the program to fifty. Selected by a jury of CAA members from a highly competitive group of applicants, the participants will receive funding for travel expenses, hotel accommodations, conference registration, CAA membership, and per diems for out-of-pocket expenditures.

At a one-day preconference colloquium, to be held this year at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the fifteen new participants will discuss key issues in the international study of art history together with five CAA-Getty alumni and several CAA members from the United States, who also will serve as hosts throughout the conference. The preconference program will delve deeper into subjects discussed during last year’s program, including such topics as postcolonial and Eurocentric legacies, interdisciplinary and transnational methodologies, and the intersection of politics and art history.

This is the third year that the program includes five alumni, who provide an intellectual link between previous convenings of the international program and this year’s events. They also serve as liaisons between CAA and the growing community of CAA-Getty alumni. In addition to serving as moderators for the preconference colloquium, the five alumni will present a new Global Conversation during the 2020 conference titled Things Aren’t Always as they Seem: Art History and the Politics of Vision.

The goal of the CAA-Getty International Program is to increase international participation in the organization’s activities, thereby expanding international networks and the exchange of ideas both during and after the conference. CAA currently includes members from sixty countries around the world. We look forward to welcoming the following participants at the next Annual Conference in Chicago.

2020 Participants in the CAA-Getty International Program

Irene Bronner, Senior Lecturer, NRF South African Research Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

Eiman Elgibreen, Assistant Professor of Art History, The Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Daria Jaremtchuk, Associate Professor of Art History, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Ganiyu Jimoh, Lecturer, University of Lagos, Nigeria, and Postdoctoral Fellow, Arts of Africa and Global Souths research program, Department of Fine Art, Rhodes University, South Africa

Mariana Levytska, Research Associate, Department of Art Studies, Ethnology Institute, UNAS (National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine)

Daniela Lucena, Head of Research Team, National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), University of Buenos Aires, Argentina

Ali Mahfouz, Director, Mansoura Storage Museum, Ministry of Egyptian Antiquities, Egypt

Priya Maholay-Jaradi, Convenor, Art History, National University of Singapore

Valeria Maria Paz Moscoso, Academic Coordinator and Advisor, Universidad Catolica Boliviana San Pablo, La Paz, Bolivia

Daria Panaiotti, Curator of Photography and Research Associate, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Aleksandra Paradowska, Assistant Professor, University of Fine Arts, Poznań, Poland

Saurabh Tewari, Assistant Professor, School of Planning and Architecture, Bhopal, India

Giuliana Vidarte, Chief Curator and Head of Exhibitions, Museum of Contemporary Art of Lima and Peruvian University of Applied Sciences, Peru

Julia Waite, Curator of New Zealand Art, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, New Zealand

Jean-Arsène Yao, University Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Côte d’Ivoire

Participating Alumni

Abiodun Akande, Senior Lecturer, University of Lagos, Nigeria

Pedith Chan, Assistant Professor of Cultural Management, Chinese University of Hong Kong

Iro Katsaridou, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki, Greece

Cristian Emil Nae, Associate Professor, George Enescu National University of Arts, Iasi, Romania

Nora Veszpremi, Research Associate, Continuity/Rupture: Art and Architecture in Central Europe 1918–1939 (CRAACE), Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic

International Review: Community-Led Engagement with Contemporary Craft, Design, and Architecture in Aotearoa

posted by CAA — October 03, 2019

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Linda Tyler, a New Zealand curator, writer, and academic who is Convenor of Museums and Cultural Heritage at the University of Auckland in New Zealand.

In the late 1990s, frustrated by the lack of a dedicated exhibition space for their work, a group of craft practitioners spearheaded an initiative to develop a dedicated craft gallery for Aotearoa (the Māori name for New Zealand). Following a successful bid for ongoing arts funding, Objectspace opened in 2004 in an old bank in the Auckland suburb of Ponsonby. It was the first of its kind, and after a dozen years of successful operation on this site, it underwent a transformation in 2017, moving into a purpose-designed building, and extending its scope to include architecture and design (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Objectspace’s new building opened in July 2017. Photo: Rebekah Robinson

Still the only public institution dedicated to craft and design in the country, in 2018 it extended its mandate even further. Seeking to increase engagement with Māori, Pacific, and Asian audiences and also to diversify the communities of makers which it supported, Objectspace launched the Maukuuku Project, a program of community-led activity, guided by the kaupapa (principles) of co-leadership, access, and advocacy.

Figure 2. Tuvalu master artist of maua talima (things created with the hands), Lakiloko Keakea is shown in this photograph framed by an example of her work. Titled Fafetu: Lakiloko Keakea, the exhibition was on view from September 30-November 11, 2018. Photo: Haru Sameshima

The first project in the new building began with a two-year engagement with members of the Tuvaluan community (a Pacific island people), culminating in a solo exhibition of craft by Lakiloko Keakea (Fig. 2). Challenging traditional notions of what types of crafts are understood to be part of the discourse, Maukuuku aims to change the system, recognizing the origin of many galleries and museums as institutions of colonization. Rather than inviting people into the gallery to work within its organization in a tokenistic way, the idea is to transform the organizational culture by turning over the gallery’s resources to a range of source communities from across Moana Oceania, Asia, and other migrant cultures who now call Aotearoa home.

Figure 3. Kim Hak, Alive, 2014, kettle and chicken. Included in the exhibition Alive: Kim Hak, June 2-July 21, 2019. Photo: Kim Hak

The second Maukuuku project, coordinated by Zoe Black, the new staff member charged with effecting the new direction at Objectspace, was Alive, by Kim Hak. Sponsored by the Rei Foundation, an Auckland-based Japanese funder dedicated to supporting research about peace and conflict, Alive brought artist Kim Hak from his home in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, to meet with twelve families who escaped the genocide in Cambodia in the late 1970s and resettled in Aotearoa as refugees. Wanting to document specific items that they brought with them—both precious and practical—Hak displayed the actual objects beside his photographs (Fig. 3). Often battered in transit, the focus on these material objects in the gallery setting prompted appreciation of the ordeal their owners had suffered and became a metaphor for the survival of their culture.

In a very short time, Objectspace has shown its ability to promote and advocate for art forms that have been marginalized, and communities that have never before been engaged by the gallery or museum sector in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Its ambition to introduce cultural change within the craft and design sector nationally, through forming co-leadership relationships with diverse communities of makers throughout Aotearoa is admirable. Already there has been increased engagement from Māori, Pacific, and Asian audiences, and it seems well underway toward fulfilling its mission to remove barriers to access.

The Maukuuku program will feature in a chapter written by Objectspace director Kim Paton for the forthcoming publication, Companion on Contemporary Craft, edited by Namita Gupter Wiggers, (Wiley Blackwell) to be published in 2020.

International Review: Vibrancy In Stone: Masterpieces of the Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture

posted by CAA — August 29, 2019

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Swati Chembakur, an architectural historian at Jnanapravaha, a center for the arts in Mumbai, India. The author is also a 2019 alumna of the CAA-Getty International Program.

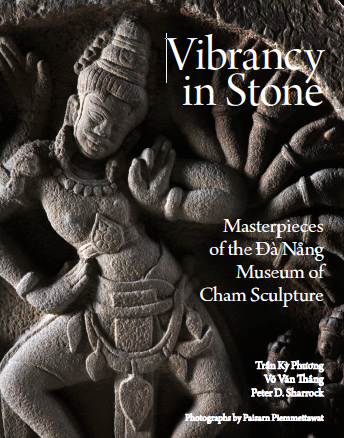

Vibrancy in Stone: Masterpieces of the Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture, by Trần Kỳ Phương, V. Văn Thắng, and Peter D. Sharrock. Photographs by Paisarn Piemmettawat (Bangkok: River Books, 2018)

In 2018, the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) partnered with the Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture in central Vietnam to produce a remarkable and visually striking centenary catalogue of its world-renowned collection of the sacred arts of the Cham people of Vietnam. The publication of Vibrancy in Stone: Masterpieces of the Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture was timed to coincide with the renovation and expansion of the museum.

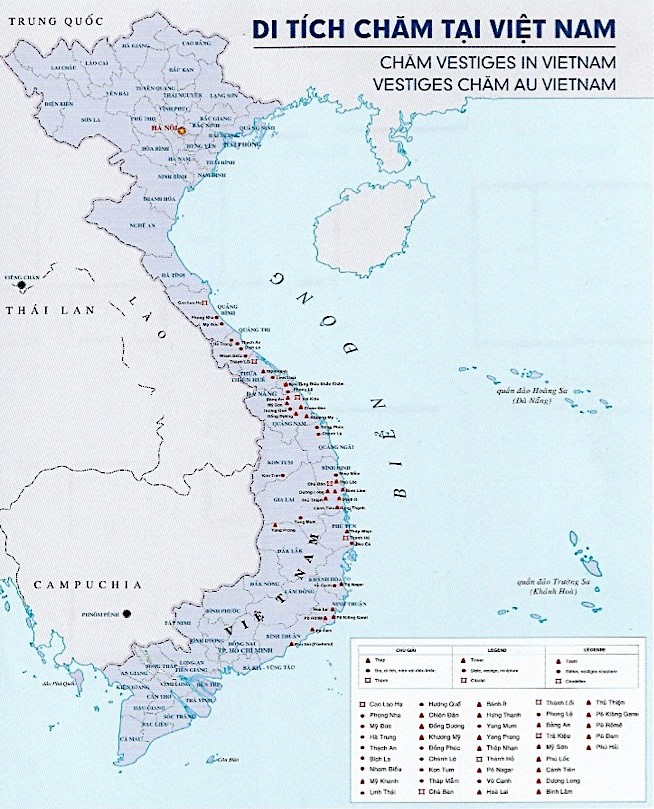

Beginning in the second century CE, settlements appeared along the central coast of what became Vietnam. The Chams probably migrated over the ocean from Borneo and were accomplished navigators. Their ports were the first call for any ship heading from China to India and the Arab world. Their role in the medieval maritime trade grew steadily and reached an apogee in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, when the great neighboring empire of Cambodia declined. The prosperity won from trade led to large scale temple construction earlier than the Cambodians.

Figure 1. Map of Cham archaeological sites in Vietnam

When tourism resumed in Vietnam after the wars of the twentieth century, the museum quickly became a prime attraction in the port city of Đà Nẵng. It is the world’s only museum devoted exclusively to the art of ancient Champa, the name given to the civilization of the Cham people. With 500 objects on display, its collection far outnumbers those in the Hanoi and Ho chi Minh City History museums, as well as the Musée Guimet in Paris.

Figure 2. Đà Nẵng Museum, Vietnam Photo: Trần Kỳ Phương

In the late nineteenth century, fifty sculptures were gathered by a French colonial administrator and amateur/enthusiastic collector, Charles Lemire, in a public garden at Tourane (Đà Nẵng), forming the embryo of the future museum collection. Some years later, French architect and archaeologist Henri Parmentier took charge of the neglected artworks and proposed a museum for their protection, which opened in 1919 (Fig. 2). He compiled the first comprehensive catalogue.

French colonial research formed the basis of Cham studies. Today a growing number of Vietnamese archaeologists and art historians are taking an active interest in this subject, expanding our understanding of the ancient art. Ethnic Cham scholars still remain few in number. Almost seventy years after Parmentier’s catalogue, a short guidebook to the museum was published about Cham history and art (Trần Kỳ Phương, 1987). It marked the first catalogue of the collection compiled by Vietnamese researchers and highlighted the link between Vietnamese and French research. After the devastating twentieth-century wars in Vietnam, some of the objects in Parmentier’s 1919 catalogue had disappeared, been damaged, or moved to other institutions. At the same time, many recently discovered artifacts have been added to the museum inventory.

Knowledge of Champa’s history, culture, and art, and an appreciation of its richness and uniqueness, has gradually progressed with the accumulation of new data and the engagement of various scholarly disciplines by both national and international scholars. Champa studies no longer appear in only French-language journals, as in the early twentieth century, but now attract a growing number of scholars from Europe, Asia, and North America, who work alongside Vietnamese experts.

Vibrancy in Stone is organized into two parts. Part I includes fourteen essays about the history and culture of Champa by Vietnamese and international scholars. Part II presents a stunningly illustrated chronology of Cham sculpture accompanied by meticulous descriptions and comments by contemporary scholars.

The introductory essay by museum director Vo Văn Thắng discusses the history of the museum, its collection, changing installations over the years, and the current renovation and expansion of the building. Subsequent essays by Kenneth Hall, John Whitmore and Đỗ Trường Giang address the importance of several Champa ports extending along the central Vietnam coast and their active role in the maritime trade network. Champa was probably never a unified state or kingdom but rather a series of loosely linked smaller polities. Its capitals were widely separated settlements on different parts of the coast, which took turns assuming hegemony over others.

Whitmore’s essay delineates fully for the first time the rise of Vijaya (in today’s Bình Đinh province) as the culture’s capital in the ninth century to its sudden demise in the fifteenth century.

Several essays address the Hindu-Buddhist religion, its rituals, archeology, and inscribed objects (by Shivani Kapoor, Ann-Valérie Schweyer, John Guy, Arlo Griffiths, Lâm Thị Mỹ Dung, and—full disclosure—myself) while others (by Trần Kỳ Phương and Parul Pandya Dhar) focus on the architecture, taking the reader through the history of Cham temples and highlighting the evolution of key construction techniques and design features that produced a series of tall, distinctive and elegant brick towers along the coastline (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Mỹ Sơn valley temple displaying long, elegant brick sanctuaries Photo: Trần Kỳ Phương

The iconography of the beautiful and vibrant Cham sculptures erected in these towers—referenced in the catalogue title—is the subject of chapters by Thierry Zéphir, Grace Chiao-Hui Tu, and Peter D. Sharrock. Cham art has hitherto been almost exclusively studied through an Indic lens but Hui-Tu’s work brings out many new and unseen Sinitic aspects in Cham sacred art. For example, a ninth century monumental sandstone Buddha from Đồng Dương monastery is seated in the “European” position with pendant feet and palms resting on the knees (Fig. 4). While Buddhas seated with pendant legs can be found in Indian, Southeast Asian, and Chinese Buddhist art traditions, this particular hand posture is seen only in China and Đồng Dương.

Figure 4. Đồng Dương pedestal from Đồng Dương, Quảng Nam. 9th century, sandstone, 30 x 177 x 70 in. (76 x 449 x 389 cm); sandstone dais supporting the Buddha, 28 x 87 x 49 in. (70 x 222 x 124 cm). BTC 177-178 Photo: Paisarn Piemmettawat

The question of the relationship between Cham and neighboring Khmers forms the core of the paper by Peter D. Sharrock. Addressing the beautiful Khmer bronze of a naga-enthroned Buddha discovered by the French in the main Cham temple outside Vijaya, he points out that this icon was never part of Cham iconography. He then uses art historical and epigraphic evidence to untie a series of long-distorting knots in the history of the Khmer-Cham relationship.

Part II of Vibrancy in Stone focuses on masterpieces of the museum, one of which is the beautiful bronze illustrated in Figure 5, found in the Đồng Dương monastery in 1978. Earlier labelled as Tārā or Prajñāparāmita, here it has been correctly identified as the female aspect of Avalokitesvara and the main cult image of the monastery.

Figure 5. Lakṣmīndra-Avalokiteśvara, 9th century bronze found in the monastery of Đồng Dương. height 6 in. (115 cm). Attributes: lotus (right hand) and conch broken at the time of discovery. BTC 1651-BTĐN 535 Photo: Paisarn Piemmettawat

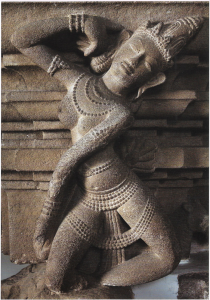

Other masterpieces include the most famous Mỹ Sơn Śivalinga pedestal (Fig. 6a-b), the only Cham sculpture that records the daily spiritual activities of ascetics performing rituals, practicing meditation, conversing, playing musical instruments, treating diseases, etc., and a widely acknowledge high relief of a Trà Kiệu dancer draped in beads (Fig. 7).

Figure 6a. Mỹ Sơn, 8th century temple pedestal displaying several daily ascetic activities, sandstone, 25 ½ x 107 x 131 in. (65 x 271 x 333 cm). BTC 6-22.4 Photo: Trần Kỳ Phương

Figure 6b. Details of the ascetic activities depicted on the Mỹ Sơn pedestal. Photo: Paisarn Piemmettawat

Figure 7. Trà Kiệu dancer/apsaras, Trà Kiệu, Quàng Nam, 11th century, sandstone, 43 x 106 in. (110 x 270 cm). BTC 118/1-22.5

Vibrancy in Stone brings together some of the most priceless and rare works of Cham art. As such, it proclaims the value and artistry of works by the Cham people whose heirs today are an ethnic minority in Vietnam. Equally important, it gathers together these beautiful and rare works of art as a resource for scholars, students, and connoisseurs alike.

The CAA-Getty International Program: Looking Forward, Looking Back

posted by CAA — August 01, 2019

This article was written by Janet Landay, project director of the CAA-Getty International Program since its inception.

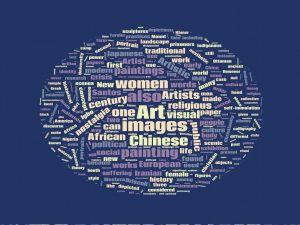

2019 participants in the CAA-Getty International Program, photographed at the Annual Conference in New York. Photo by Ben Fractenberg

This is open season for the CAA-Getty International Program; that is, we’re accepting applications from international scholars between now and August 23rd to participate in next year’s program at the Annual Conference in Chicago. This will be the ninth year of the program and we’re looking for academics, curators, or artists who teach art history from countries not well represented in CAA’s membership (primarily non-Western countries from the global south, all parts of Asia, and Eastern Europe). Specifically, we want to bring scholars who are advancing our understanding of the visual arts, be it through art history, visual studies, or any number of intersecting disciplines, such as aesthetics, history, post-colonial studies, gender studies, cultural heritage research, etc. The range of topics addressed by participants since the program began nine years ago is remarkable, as exemplified in last year’s programs included at the end of this article.

The mission of the CAA-Getty International Program is to bring new voices to the CAA community to enrich the conversation about globalization and inclusion in visual arts scholarship. Since it began in 2012, the program has brought 120 scholars from 46 countries to its conferences, including representatives from Argentina, Albania, Bangladesh, Benin, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chile, China, Croatia, Cuba, Czech Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Estonia, Ghana, Greece, Haiti, Hungary, Iceland, India, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, South Africa, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, and Vietnam. Many of these scholars have returned to CAA conferences as speakers, session chairs, and members of CAA’s International Committee. They have also contributed articles to CAA’s publications and collaborated with scholars in the United States that they met while attending a conference.

Map showing home countries of 2019 CAA-Getty International Program participants. Map provided by Nazar Kozak.

Each year, US-based CAA members serve as hosts to the international scholars, introducing them to colleagues, guiding them through the conference’s vast array of sessions and programs, and frequently taking them to museums and collections in town. To date, over 60 CAA members have participated in the program, supported with honoraria from the National Committee for the History of Art.

In 2020, we will bring fifteen new scholars and five alumni to the Chicago conference. Please help us spread the word of this grant opportunity to colleagues or institutions in the regions mentioned above by sharing this link to the program’s description and application.

And if you would like to participate as a host, send me an email at jlanday@collegeart.org.

What follows is the program for two key events from the 2019 CAA-Getty International Program: a preconference colloquium on February 12th on international issues in art history at which twenty scholars participated, and an alumni conference session on February 14th that featured five CAA-Getty alumni. Included below is the program for the February 12th colloquium, followed by the abstracts for the February 14th alumni conference session.

Word cloud showing most frequently used words in the 2019 Preconference Colloquium of the CAA-Getty International Program. Illustration provided by Nazar Kozak.

PROGRAM

GLOBAL CONVERSATIONS 2019

PRECONFERENCE COLLOQUIUM

Tuesday, February 12, 2019

Starr Foundation Hall, Parsons School of Design

8:30 AM Coffee, welcome, and introductions

9:15 AM Examples of Defining or Constructing Aesthetics in Chinese and Japanese Art

Chair: Chen Liu, Harvard-Yenching Institute, Harvard University, 2018-19

The Making of Scenic Sites: Landscape Painting, Tourism and Nationalism in Republican China

Pedith Chan, Chinese University of Hong Kong

Art by Japanese Prisoners in New Zealand during WWII

Richard Bullen, University of Canterbury, New Zealand

Lucy Driscoll and Developing a Theory of Chinese Painting

Jian Zhang, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou

CAA-Getty International Program preconference colloquium, February 12, 2019. Photo by Ben Fractenberg

10:30 AM Orientalism/Occidentalism

Chair: Nadhra Khan, Lahore University of Management Sciences, Pakistan

From Occidentalism to an Occidentalizing Art: An Iranian Gaze to the Occident

Negar Habibi, University of Geneva, Switzerland

Deconstructing Imperialism: The Intersection of Religion, Politics, and Design in the Iconography of a Christian Saint

Halyna Kohut, Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Ukraine

Orientalism and Female Portraiture in Nineteenth-Century Painting in Romania

Oana Maria Nicuță Nae, George Enescu National University of Arts, Iasi, Romania

11:45 AM How Do We Approach Religious Art?

Chair: Nazar Kozak, Department of Art Studies, Ethnology Institute, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

The Last Judgment in Spanish America as Social Rhetoric of Salvation and Damnation

Tamara Quírico, State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Dancers, Musicians, Brahmins and Ṛṣis: Understanding the Temple Worship of the Pāśupata sect in Angkor, Cambodia

Swati Chemburkar, Southeast Asian Art and Architecture, Jnanapravaha, Mumbai, India

You Cannot See It: Access to Religious Artistic Materials

Stephen Fọlárànmí, Ọbáfémi Awólọ́wọ̀ University, Ilé-Ifè, Nigeria

1:00 PM Lunch

2:30 PM The Body, Identity, and Artistic Agency

Chair: Katarzyna Cytlak, Center for Slavic and Chinese Studies, University of San Martín, Argentina

Shifting Female Identity: Female Cross-dressing in Southeast Nigeria

Chukwuemeka Nwigwe, University of Nigeria, Nsukka

Challenging the “Unconscious”: Agnaldo Manoel dos Santos and the Revision of Afro-Brazilian Art

Juliana Ribeiro da Silva Bevilacqua, University of Campinas (Unicamp), Brazil

The Reinvention of the Body in Volatile Times: Political and Artistic Intersections between Buenos Aires and New York in the 1980s

Viviana Usubiaga, National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), University of San Martín/University of Buenos Aires, Argentina

3:45 PM Politics and Art in Dark Times

Chair: Sarena Abdullah, School of the Arts, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang

A Flame For Freedom

Marko Stamenkovic, ZETA Contemporary Art Center, Tirana, Albania

Sanitizing Memory through Erasure: Post-apartheid Nostalgia in Contemporary Visual Art Practice

Zamansele Nsele, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

The Crisis Displayed: Greece’s Participation at the Venice Art Biennale

Iro Katsaridou, Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki, Greece

5:00 PM Wine Reception

GLOBAL CONVERSATIONS 2019

ALUMNI CONFERENCE SESSION

ABSTRACTS

Thursday, February 14, 2019

Creative Pedagogy: Mapping In-between Spaces Across Cultures

Nazar Kozak (Chair), National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

Art-historical curricula tend to provide imaginary “racks” on which each artwork could be assigned to chronological and geopolitical shelves. In practice, however, such systems has difficulties in accommodating phenomena that fall in-between proposed categorizations. Their presence in art-historical classrooms corresponds to cosmology ‘s Dark matter: it shapes the Universe while remains directly unobserved. Hybrid phenomena have produced an important impact on art scenes across historical periods and cultures, and illumination of this impact plays crucial role in making art history more fully global discipline. This session addresses cross-cultural entanglements and overlaps in which borders looses their fix and reveals their porosity. Structured around creative pedagogy it discusses specific historic cases from the teaching perspectives moving towards inclusive and collaborative paradigm especially in mixed-class environments engaging students and faculty from different countries. The panelist, who are the CAA-Getty International Program alumni from Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, share their teaching methods that proves efficiency in navigating across cultures as well and theoretical optics providing optimal focus on transcultural dialog and reciprocal enrichment.

From left to right: Chen Liu, Nazar Kozak, Katarzyna Cytlak, Nadhra Shahbaz Khan, and Sarena Abdullah at the CAA-Getty International Program alumni conference session, February 14, 2019. Photo by Ben Fractenberg

An Italian in China: The Curious Case of Giuseppe Castiglione

Chen Liu, Tsinghua University

What happens when China and the West encounter each other? A clash of traditions may generate unexpected art forms that defy categorization, as tellingly revealed in the life and works of the multi-talented Italian Jesuit artist Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), court painter to three Qing Emperors. Despite his popularity in China both during and after his lifetime, he is surprisingly little known in the West beyond those who specialize in classical Chinese art, with sparse literature in languages other than Chinese (mainly in Italian and French). Existing studies of Castiglione’s works, focusing largely on his paintings, tend to emphasize the “Western” trend he initiated in early modern China or his fusion of “European” and “Chinese” traditions, leading to oversimplification of both. A novel teaching course featuring cultural hybridity in both its subject and audience (a mixed group of Chinese and Western students) may help address such problems of transcultural interpretation and reception as exposed by the curious case of Castiglione. Using Castiglione’s art – painting, decoration and architecture – as a mirror, and by posing previously neglected questions such as “what is ‘non-Chinese’ or ‘non-Western’ in his works, and “which ‘Chinese’ and ‘European’ artistic styles/techniques did he adopt, adapt, or reject”, the course seeks to stimulate more profound reflections on the sophisticated, sometimes ambiguous traditions of both Chinese and European art, their compatibility and incompatibility, and to illuminate the confused in-between areas.

Pedagogy of the Transborders: Reviewing East European art from the perspective of transatlantic cultural exchanges with Latin American and African cultures

Katarzyna Cytlak, Centro de Estudios de los Mundos Eslavos y Chinos, Universidad Nacional de San Martín

Developed since the 1990s by Latin American thinkers, decolonial theory became an effective tool to teach East European art. Concepts, such as “border thinking” (Walter Mignolo) and “transmodernity” (Enrique Dussel), which dealing with bicultural identity in Latin America and postulating a non-hierarchical, inter-epistemic dialogue between cultures, offer a new framework to reconsider transatlantic artistic exchanges and cultural polarizations within the European continent. The paper will analyze how transmodern and decolonial approaches could shed new light on East European art and its dialogue with non-Western cultures. Quotations of customs and rites from Polish folklore by the Polish/Mexican artist Marcos Kurtycz were the result of his biculturalism, as well as an artistic strategy aiming at distinguishing himself on the Mexican scene. Self–identification with African cultures and politics by the Polish artists of the 1980s (Marek Sobczyk, The Luxus Group) could be explained as proof of the artists’ criticism of the Non-Aligned Movement, the symptom of their “radicalized utopian inclusivity” (Boris Groys), and as their critical comment on the late Socialist societies in the processes of Westernization.

Images of Guru Nanak: Locating Patterns of Words in Images

Nadhra Shahbaz Khan, Lahore University of Management Sciences

Traditional arts in the Indian subcontinent are strongly allied to oral traditions and to written text including both folklore and literature. Examples of these abound in secular and religious realms and are manifest in a large body of miniature paintings and murals showing the Hindu stories of Heer-Ranjha, Sassi-Punnoo and Dhruv Bhagat and relief panels illustrating Buddhist jataka tales and Hindu epic poems such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata. This paper maps the depiction of Guru Nanak, the first of the ten Sikh gurus, and their dependence of the Indian visual vocabulary taken from folklore, literature and cultural practices. He is usually painted with a fixed set of attributes, each laden with references to cultural practices and beliefs: some long forgotten, others have remained current until this day. Modern interventions however, have obscured meanings of many of these concepts and practices making it difficult today to fully understand their significance in their iconographic program. Refreshing the forgotten relationship between the word and image promises to lead to creative pedagogical possibilities where realms of imagination, rendition and performance can be navigated to connect not only with the creators and viewers of art but also the ones who dwell in it.

Cross Cultural Encounters through Creative Pedagogy in Teaching Art History

Sarena Abdullah, Universiti Sains Malaysia

This paper explains and discuses my recent and first Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) with an American university within the context of students’ cross-cultural encounters imbedded through Art History subject(s). In the 15 weeks of Malaysian Modern Art (VHS 202) and Selected Topics In Asian Art (ARTH 294) class, my American collaborator and me, designed and aligned our art history classes pedagogy cross-culturally taking in various considerations of Malaysian and American context into our teaching outcome. This paper will discuss how we have adopted and adapted the COIL module in our own classes, and innovate our collaborative engagements using Facebook as our main platform. From tasks such as personal introductions of students from both Malaysian and American classes, group videos of their cultural/national background, to producing group videos on artworks and /or material culture from local institutions, to completing cross collaboration group work tasks—this pedagogical approach had managed to expose students to different cross-cultural realities and encounters (and even time zones) weaved into their learning experiences. This paper will discuss the context of such creative pedagogy in the context of how Art History can also be a platform to disseminate creative knowledge today.

International Review: Sun and Sea in Venice, Lithuania’s Prize-Winning Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale

posted by CAA — July 25, 2019

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Inesa Brasiske, a Lithuanian art historian, lecturer, and recent graduate from the program in Modern and Contemporary Art: Critical and Curatorial Studies (MODA) at Columbia University, New York.

Figure 1. Sun & Sea (Marina), opera-performance by Rugile Barzdziukaite, Vaiva Grainyte, Lina Lapelyte at Biennale Arte 2019, Venice. Photo: © Andrej Vasilenko

Upon entering the former shipyard in the secluded Marina Militare complex located a few steps from the Arsenale, one finds a beach. More than a dozen sunbathers lie drowsily on pastel colored towels among their absentmindedly-scattered stuff, preoccupied with the usual holiday business (Fig. 1). One by one they sing out their monologues, occasionally growing into undulating choruses. The performers chant their personal dramas, complaints, and joys alongside sunscreen instructions and deadpan morning routines as viewers peruse the scene from above (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Sun & Sea (Marina), opera-performance by Rugile Barzdziukaite, Vaiva Grainyte, Lina Lapelyte at Biennale Arte 2019, Venice. Photo: © Andrej Vasilenko

An opera-performance for thirteen voices, Sun & Sea (Marina) was selected to represent Lithuania at this year’s Venice Biennale, winning the country its first Golden Lion for best national pavilion. Noted by the jury for its experimental spirit and site-specificity, the work was created by three Lithuanian artists: filmmaker and director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, writer Vaiva Grainytė, and composer and artist Lina Lapelytė. It is the second time the all-female trio united their forces in this genre. Their debut work, the opera Have a Good Day! (2013), focused on the inner lives and work routines of cashiers in a shopping center. With this follow-up, the artists continued to tap into the subject of reckless consumerism, accompanied by the same physical and emotional exhaustion that framed their first work, this time taking their exploration in an eco-critical direction.

The libretto is a set of individual, discrete stories stitched together by Grainytė who, with a poet’s economy, delivers a memorable spectrum of characters, including a wealthy mother recounting her son’s travel adventures, a workaholic engaged in self-analysis, and twins envisioning a 3D-printed biosphere. The text is charged with humor and absurdist juxtapositions in a surrealist vein; viewers witness an uneasy morphological sisterhood of floating jellyfish with plastic bottle caps, disturbing scenarios of picking chanterelles in the midst of winter, or drinking piña coladas at a barrier reef. These evocative narratives unfold through a minimalist score for synthesizer and voice composed by Lapelytė and sung by a group of performers with divergent musical backgrounds. Catchy melodies with repeating pulsing patterns running through high pitched arias and dreamy lullabies are responsible to a large extent for luring viewers into this ambiguous zone of relaxation and oblivion in the face of looming ecological disaster.

One of the most striking aspects of Sun & Sea (Marina) is the atypical positioning of the viewers vis-à-vis the scene, as they experience the opera-performance while looking down from the mezzanine which frames the sandy seaside into a horizontal tableau peppered with human and, occasionally, other-than-human bodies (Fig. 3). The director and scenographer, Barzdžiukaitė, brings a filmmaker’s eye to the work; the most recent of her own films is itself calibrated on an aerial perspective of a cormorant colony at the Lithuanian seaside. In the opera, the specific viewpoint works as a conceptual device aptly playing into the ecological theme of the piece. The non-human perspective that the audience embraces points to the limits of the anthropocentric view and suggests something alarming and at the same time slightly comical about the human species in all its flatness.

Figure 3. Sun & Sea (Marina), opera-performance by Rugile Barzdziukaite, Vaiva Grainyte, Lina Lapelyte at Biennale Arte 2019, Venice. Photo: © Andrej Vasilenko

The opera was first shown in Lithuania in 2017. Arranged in the atrium of the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius, the Lithuanian version was a slightly longer piece, repeated as a series of performances throughout one day. After its premiere, the work traveled to Germany, where it was shown in a former movie theater as part of the Staatsschauspiel Dresden theater’s repertoire. It is in Venice, however, that the work has been given its most complex treatment, fully exposing its eco-critical and social potential. The opera turned into an endurance performance-cum-installation, running continuously for eight hours at a time, with no beginning or end, once (and more recently twice) a week, while for the rest of the time it is presented as a (post-apocalyptic?) sound installation devoid of any living bodies or voices. The authors did not limit their open-ended approach to experimenting with new formats alone; they also responded to local resources and communities. Under the curatorship of Lucia Pietroiusti, Curator of General Ecology and Live Programs at the Serpentine Galleries in London, the artists invited Venetian residents to perform the piece during the long run of the Biennale, commissioned the last existing printing house in the city to print the exhibition catalogue, and, together with Benjamin Reichen from the Åbäke design collective, collaborated with inmates of a local prison in a silkscreen workshop to produce the cover of the opera’s LP.

Figure 4. The Marina Militare complex, where Sun & Sea (Marina) is installed. Photo: © Andrej Vasilenko

Where much of ecologically oriented art tends to amplify our sensations in order to enable us to hear more sharply and see more clearly the scale of the climate crisis and ecological collapse, Sun & Sea (Marina) operates on a rather different register. A condensed image of the status quo of the contemporary world and its dystopian future is communicated through the recognizable, the quotidian, the banal. The durational aspect of the work, which puts seemingly surplus non-scripted real-life experiences on view—performers eating their lunch, chatting, getting exhausted and resting, kids running free and playing around, dogs barking—strengthen this realistic effect as does the participatory element inviting viewers to spend some time on the beach among the singing performers.

In the end, there might be no sea in the shipyard, but the beach there is real, and it mirrors our own day-to-day needs and deeds enmeshed in the forces of late capitalism punctuated by the logic of efficiency and endless consumption of goods as well as experiences. The end of the world here is void of spectacular images and sounds, but rather presents itself as what environmental writer Rob Nixon terms a “slow violence,” wherein ecological catastrophe does not occur in a sudden blaze but in a gradual relentless deterioration. Representation of the latter, Sun & Sea (Marina) seems to propose, curiously lies between accurate account and eloquent visionariness.

The Getty Foundation to Fund the CAA-Getty International Program for a Ninth Year

posted by CAA — June 12, 2019

CAA-Getty Scholars at the 2019 Annual Conference in New York. Photo: Ben Fractenberg

The Getty Foundation has awarded CAA a grant to fund the CAA-Getty International Program for a ninth consecutive year. The Foundation’s support will enable CAA to bring twenty international visual-arts professionals to the 108th Annual Conference, taking place February 12-15, 2020 in Chicago. Fifteen individuals will be first-time participants in the program and five will be alumni, returning to present papers during the conference. The CAA-Getty International Program provides funds for travel expenses, hotel accommodations, per diems, conference registrations, and one-year CAA memberships to art historians, artists who teach art history, and museum curators.

The application portal is now open. Grant guidelines and the 2020 application can be found here.

“The Getty Foundation is proud to continue its commitment to the CAA-Getty International Program and offer support that brings together diverse scholars from around the world,” says Joan Weinstein, acting director of the Getty Foundation. “CAA’s dedication to this joint program strengthens the annual conference and builds the field of art history as a global discipline.”

Since the CAA-Getty International Program’s inception in 2012, it has brought over 120 first-time attendees from 46 countries to CAA’s Annual Conference. Historically, the majority of international registrants at the conference have come from North America, the United Kingdom, and Western European countries. The CAA-Getty International Program has greatly diversified attendance, adding scholars from Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, Africa, Asia, Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, and South America. The majority of the participants teach art history, visual studies, art theory, or architectural history at the university level; others are museum curators or researchers.

One measure of the program’s success is the remarkable number of international collaborations that have ensued, including an ongoing study of similarities and differences in the history of art among Eastern European countries and South Africa, attendance at other international conferences, publications in international journals, and participation in panels and sessions at subsequent CAA Annual Conferences. Former grant recipients have become ambassadors of CAA in their countries, sharing knowledge gained at the Annual Conference with their colleagues at home. The value of attending a CAA Annual Conference as a participant in the CAA-Getty International Program was succinctly summarized by alumnus Nazar Kozak, Senior Researcher, Department of Art Studies, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine “To put it simply, I understood that I can become part of a global scholarly community. I felt like I belong here.”

Read our Member Spotlight with Nazar Kozak.

About the Getty Foundation

The Getty Foundation fulfills the philanthropic mission of the Getty Trust by supporting individuals and institutions committed to advancing the greater understanding and preservation of the visual arts in Los Angeles and throughout the world. Through strategic grant initiatives, it strengthens art history as a global discipline, promotes the interdisciplinary practice of conservation, increases access to museum and archival collections, and develops current and future leaders in the visual arts. It carries out its work in collaboration with the other Getty Programs to ensure that they individually and collectively achieve maximum effect.

International Review: Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art by Yiqian Wu

posted by CAA — June 04, 2019

Exhibition Review: Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei, February 2 –May 5, 2019, Sydney, Australia

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Yiqian Wu, a graduate student at the University of Sydney.

Figure 1. Exhibition banner. The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. February 5—May 5, 2019. Photo: Yiqian Wu.

How should we humans perceive our relationship with nature? An ancient Chinese perspective of the human/nature relationship was offered by Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei (Fig. 1), which was recently exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. This exhibition offered the viewer a rare opportunity to closely examine eighty-seven Chinese national treasures with the themes of “Heaven and Earth,” “Seasons,” “Places,” “Landscape,” and “Humanity.”

This article focuses on three works of arts drawn from the themes of “Heaven and Earth,” “Seasons,” and “Landscape,” and explores how each one exemplifies the Chinese philosophical concept of tian ren he yi (天人合一), unity or harmony between heaven, nature, and humanity.

1. Humanity is joined with heaven and earth

Figure 2: Tri-Ring symbolizing Heaven, Earth, and Humanity, Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE), jade, nephrite, outer diameter 4 1/2 in. (11.75 cm). The Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, Australia. Photo: The collection of National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Under the theme “Heaven and Earth” a jade object titled Tri-Ring symbolizing Heaven, Earth and Humanity (Fig. 2) presented the viewer with the ancient Chinese worldview of human/nature relationships. The three individual rings, representing heaven, earth, and humanity, are interlocked by a mortise and tenon joint, allowing each ring to rotate on its axis line. For instance, this tri-ring constructs a globe when unfolded and becomes three concentric rings when laid flat.

Curator Cao Yin explains that the inner ring represents heaven, as it is carved with the motif of the sun, clouds, and stars. The outer ring, decorated with mountains and oceans, represents the earth. The middle ring, depicting the motif of the dragon to symbolize emperors, represents the human world led by emperors.

The rotation of the tri-ring symbolizes the dynamics of energy flowing and exchanging among three powers of the universe. And the interlocked connection between three rings implies the mutual restraint of power between heaven, earth, and humanity. The arrangement of three rings reflects the ancient Chinese belief that humans mediate between heaven and earth and are the central component of the ecosystem.

2. Humanity adapts to the changes of nature

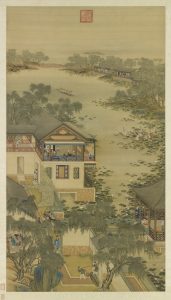

Figure 3: “The sixth month” from The Twelve Lunar Months, Qing dynasty (1644–1911 CE), hanging scroll, ink and paint on silk, 126 x 50 in. (320 × 127.6 cm). The Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, Australia. Photo: The collection of National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Under the theme of “Seasons,” a scroll painting from the Qing dynasty displays how ancient Chinese people adapted themselves to June, one of the hottest months in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 3). Since animals prefer to hide in the shade to avoid the heat of June, this month was also called by ancient Chinese as fu yue (伏月, the month of hiding). Since June is also the season for the blossom of lotus flowers, he yue (荷月, the month of the lotus) was another name for June in ancient China. As the painting shows, people enjoy various recreational activities to reduce the heat, such as enjoying the breeze in a pavilion or going fishing and picking lotus flowers by riding boats on the pond.

Seasonality is a natural phenomenon that signifies the irresistible power of nature in regulating human lives. The ancient Chinese people believed that adapting to the change of seasons could result in a good harvest and personal health. In order to positively respond to nature, they divided twelve lunar months into twenty-four divisions of the solar year in their traditional calendar. Each solar term corresponds to relevant folk customs, including the timing of agricultural activities and recipes for seasonal food therapy. These cultural traditions emphasize the important role of nature in guiding everyday lives of human beings and suggest that people benefit from adapting to seasonal variation.

3. Nature is humanity’s spiritual homeland

Figure 4: Attributed to Wang Meng (1308–1385 CE), Fishing in Reclusion on a Flowering River, Yuan dynasty (1279–1368 CE), hanging scroll, ink on paper, 51 x 23 in. (129 × 58.3 cm). The Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, Australia. Photo: The collection of National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Shan-Shui (山水, mountains and water) is a Chinese term for landscape. These two Chinese characters present the essence of the theme “Landscape” in this exhibition. In Chinese culture, mountains and water are not only the key components of natural landscape, but also the spiritual home for literati and recluses.

Liu Yinxing defines recluses as those politically exiled intellectuals living in times of war and regime change, who abandon themselves to the peace and tranquility of natural landscape. Wang Meng’s landscape painting (Fig. 4) portrays a recluse’s dreamland, in which he befriends the mountains and river. As pointed out by Liu Chengzhang, Wang Meng spent decades as a recluse. As a Han ethnic painter living in the Yuan dynasty ruled by Mongolians, Wang Meng possibly regarded himself as a political refugee and sought comforts and transcendence in nature, his spiritual homeland.

As the caption explains, the painting’s poetic imagery, such as chains of mountains, a river, peach blossoms, and a fisherman, were derived from The Peach Blossom Spring (桃花源记), a prose text written by the Six Dynasties recluse and poet Tao Yuanming. In keeping with Tao’s rendering of the ideal world, Wang Meng manifested the seamless fusion of human beings and nature by immersing the body of the human figure within the boundless beauty of nature. The relationship between the tiny human figures and the sublime landscape conveys the human being’s great reverence for nature and expresses Wang Meng’s (the reclusive painter’s) desire of being detached from the mundane world and returning to his spiritual homeland, nature.

In conclusion, the exhibition Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei presented to a predominantly Western audience three main ways that ancient Chinese people pursued their harmonious relationship with nature: emphasizing that humans live in unison with nature, humans will thrive by responding to seasonal variation, and nature offers humans a spiritual home.

CIHA World Congresses in Florence and São Paolo

posted by CAA — May 20, 2019

A SESSION AT THE 2019 CAA CONFERENCE INTRODUCED TOPICS FOR The 35th World Congress, Parts 1 and 2, of the Comité International d’Histoire de l’Art (CIHA)

David Roxburgh, Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Professor of Islamic Art History at Harvard University, contributed the following article about the next two world congresses organized by CIHA so that CAA members can consider attending and participating. Professor Roxburgh is the current president of the National Committee for the History of Art (NCHA), the US affiliate of CIHA that connects the international committee’s work with CAA and its members to sustain the global exchange of art historical work.

Motion: Transformation and the Life of Artworks, the session sponsored by NCHA at the 2019 CAA Annual Meeting in New York, brought together scholars from the organizing committees of Italy and Brazil who will share the quadrennial 35th CIHA World Congress. The themes are Motion: Transformation, taking place in Florence in 2019, and Motion: Migrations, taking place in São Paolo in 2020. The CAA panelists comprised Marzia Faietti (Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence), Claudia Mattos Avolese (Universidade Estadual de Campinas, São Paulo), Marco Musillo (Kunsthistoriches Institut, Florence), and Christina Strunck (Friedrich-Alexander-University, Erlangen-Nürnberg), with Jesús Escobar (Northwestern University) serving as respondent and Nicola Courtright (Amherst College) as chair. The thoughtful remarks of Professor Jesús Escobar are included here for those who could not attend the panel.

The CIHA Congress in Florence will be held September 1-6, 2019, and in São Paulo September 13-19, 2020. The final program for Florence is now available.

For the São Paulo program, a call for paper submissions is available here.

NCHA recently awarded 12 travel grants to graduate students from PhD programs in the history of art from across the United States to attend the 35th CIHA Congress in Florence. A competition will be announced early in 2020 for graduate students planning to attend the CIHA Congress in São Paulo. We hope to see many art historians working in the US in Florence and São Paulo.

International Review: Opening of the Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, United Arab Emirates by Sabrina DeTurk

posted by CAA — March 21, 2019

The following article was written in response to a call for submissions by CAA’s International Committee. It is by Sabrina DeTurk, associate professor, College of Arts and Creative Enterprises, Zayed University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Fig. 1: Exterior of Jameel Arts Center, Jaddaf Waterfront, Dubai, UAE. Photo by Sabrina DeTurk.

In November 2018, Dubai witnessed the opening of the Jameel Arts Centre, the city’s first non-commercial contemporary arts space (Fig. 1). Located on the banks of the Dubai Creek, in the still-developing area of the Jaddaf Waterfront, the center is a project of the Saudi-based organization Art Jameel, a foundation focused on arts and culture programming that is sponsored by the Jameel family. The Jameel Arts Centre will be programmed as a kunsthalle, featuring temporary exhibitions showcasing works drawn from the Jameel collection as well as commissioned works by contemporary artists and those on loan from other institutions. Community events and educational outreach are also key elements of the center’s programming initiatives and the 107,640 square-foot space includes facilities such as an open-access library of over 3,000 volumes as well as coworking areas. There will also be a sculpture park as well as an outdoor arena for performing arts or film screenings.

The Jameel Arts Centre’s inaugural exhibitions included a series of artist’s rooms featuring the work of women artists from the Middle East whose work has garnered critical acclaim though not always international visibility. Maha Al Malluh (Saudi Arabia), Mounira Al Solh (Lebanon), Lala Rukh (Pakistan), and Chiharu Shiota (Japan) showed work that reflected on the personal, communal, and political, sometimes all in one piece.

In Maha Al Malluh’s sculpture, Food for Thought, dozens of well-used cooking pots of all sizes are affixed to two walls of the gallery with their undersides facing the viewer. The burns, scrapes and dents on these surfaces become both a pattern and a portrait, suggesting the many meals, large and small, cooked and served in these vessels. The pots invoke both an individual and collective activity of dining. One senses that these pots have traveled far to reach their current destination, perhaps reflecting the experience of refugees who have fled from so many troubled parts of the region, often with few possessions other than simple cooking utensils and basic clothing.

Lala Rukh’s minimalist and meditative prints and video speak to the personal experience of her mother’s death as well as the changing political landscape of Southeast Asia in the 1990s. However, the darkness of the room in which the works are displayed made it all but impossible to read the contextualizing and interpretive materials that are necessary to understand the meaning of Rukh’s subtle forms.

Fig. 2: Installation view of Chiharu Shiota, Departure (2018). Photo by Sabrina DeTurk.

The inclusion of a sculptural installation by Chiharu Shiota, featuring an Arabian dhow (sailing vessel) sourced from a local boatyard, struck an odd note among the rooms (Fig. 2). While Shiota’s sculpture, which featured her signature webs of red yarn, was visually compelling, there was little sense, beyond the inclusion of the local boat, of its contribution to the larger dialogues encouraged by the exhibitions. In an image-obsessed city such as Dubai, one can’t help but wonder if this installation served more as an Instagrammable photo opportunity than as a work of serious contemporary art.

The inaugural group exhibition at Jameel Arts Centre, Crude, was curated by Murtaza Vali and featured the work of eighteen artists and artist collectives. In the show’s catalogue, Antonia Carver, the Director of Art Jameel, described the exhibition as “presenting an innovative material reading of a substance so crucial in shaping local and regional histories and cultures.” The included works run the gamut from archival photographs to video to sculptural installations to found objects and reflect a diversity of artistic approaches to the cultural, political, and economic significance of oil in the region throughout the last six decades.

Fig. 3: Houshang Pezeshknia, Portrait d’homme (1949). Photo by Sabrina DeTurk.

The earliest works in the show, documentary photographs by the Iraqi, Latif Al Ani, and paintings by the Iranian, Houshang Pezeshknia (Portrait d’homme, 1949, Fig. 3), highlight the role that the discovery of oil played in shaping the modern culture and identity of both countries. Al Ani’s photographs focus on the material benefits of the oil industry, featuring images of new, modernist housing developments and smiling children showing the bottles of milk now provided as part of the government school lunch program. Pezeshknia’s paintings are more introspective; their rough brushstrokes emphasize the harsh features of those who work on the pipelines and the scars left on the Iranian landscape by the new technologies of oil extraction.

Several artists in the exhibition drew on found images and archival film footage for their works. These include Raja’a Khalid, whose Desert Golf series (2014) uses vintage print media from American publications such as Life magazine to document the seemingly inexorable, if equally inexplicable, compulsion that expatriate oil executives had for finding ways to play golf in the hostile desert landscape. In several of these images, bewildered local residents look on, setting up an us/them dichotomy and pervasive sense of cultural difference that still marks expatriate and local relations in the Gulf region.

Fig. 4: Installation view of Crude exhibition. Monira Al Qadiri, Flower Drill (2016) is on the wall. Photo by Sabrina DeTurk.

Sculptural installations featured prominently in the exhibition. For example, Monira Al Qadiri’s Flower Drill (2016, Fig. 4), displayed high on the wall in one of the galleries, features fiberglass forms based on the design of drill heads and coated in two-toned automotive paint, connecting the work to both the initial and final stages of oil production and consumption. Alessandro Balteo-Yazbek’s Last Oil Barrel is a tiny wooden sculpture of a barrel, whose price is linked to oil futures and whose value will be determined only at some unspecified date in the future when a sale is fixed, reflecting the connections between the commodity value of both art and oil. The artist identifies the date of the work as “postponed,” indicating that it remains in some way incomplete until that time.

Although Crude was an intellectually rigorous and aesthetically compelling first exhibition from the Jameel Arts Centre, it remains to be seen whether there will be a sufficient audience for this type of show in Dubai over the long term. While the center’s opening weekend saw packed galleries, a weekday in January found the author almost alone in the spaces. The question of representation and inclusion of Emirati artists will undoubtedly also be raised at some point in the center’s development.

Fig. 5: Installation view of Crude exhibition. Hassan Sharif, Slippers and Wire (2009) is in the foreground. Photo by Sabrina DeTurk

A sculpture by the pioneering Emirati conceptualist artist Hassan Sharif (Fig. 5) was included in Crude and works by Emirati sculptors Shaikha Al-Mazrou and Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim were shown in the lobby and outside garden respectively. However, this is but a small sample of the variety of contemporary art being produced in the United Arab Emirates and local artists may, understandably, begin to call for greater visibility in this high-profile contemporary arts space. The Jaddaf Waterfront remains under construction and as yet there is not a sustained community to support the idea of the Jameel Arts Centre thriving as a local creative hub. That said, the potential for growth and development is there and the openness with which the center is positioning itself is welcome in a city where the arts scene can often feel closed and difficult to penetrate. Jameel Arts Centre is a welcome addition to the creative landscape of Dubai and will hopefully continue to develop as a space for contemporary expression.